TORONTO – On a Friday or Saturday night, 15-year-old Maggie Fei can often be found on the grounds of the David Dunlap Observatory in Richmond Hill, Ontario, eyes to the sky.

Maggie is a volunteer at the DDO, an observatory run by volunteers from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Toronto Centre. Maggie’s not there to get her required volunteer hours – she obtained those long ago. Maggie’s there because she loves science.

“I’m interested in a lot of different things,” she said. “But I know I want to study some kind of science as my major in university.”

But studies show that, though there’s been an increase in women pursuing careers in science, technology, engineering and math fields – referred to as STEM – men still dominate.

A 2010 study by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada found that in 2008-2009 there were 15,933 males enrolled in natural sciences and engineering doctorates (full time), while there were 15,687 females. Though that may seem like a small difference, the widest gap was found in engineering and computer science programs with 4,110 males enrolled and just 1,047 females enrolled. In math and physical sciences, it was 2,061 males to 885 females.

READ MORE: Women less likely to choose university program in science, tech, engineering, math: StatsCan

In life sciences, such as biology and medicine, the gap is narrowing, with some researchers suggesting that there will soon be more women than men in the field.

Is it that boys are simply better at math and sciences?

That doesn’t appear to be the case. In fact, some studies suggest that girls do better in school. One such study published in the American Psychological Association’s journal Psychological Bulletin in April 2014 by researchers at the University of New Brunswick found that girls performed better in every subject in school.

Get daily National news

Planting the seed

Larissa Vingilis-Jaremko, who founded the Canadian Association of Girls in Science (CAGIS) when she was just nine years old, believes that in order to get more girls interested in science, the influence has to come from two sources – home and school. The lack of interest in science, she believes, is formed at a young age.

“It’s just a lack of exposure, and that lack of exposure builds over time as girls are getting into Grade 7, 8, 9, into high-school-grades,” Vingilis-Jaremko said. “And that’s sometimes when the gap starts developing.”

There’s also the role that media plays: the separation between boys’ and girls’ toys still continues, with most of the science and tech-based toys aimed at boys. Vingilis-Jaremko also feels that the way we behave at home – maybe a mother saying that she’s no good at math and telling her child to go ask her father for help – subtly influences the perception of math, science and tech as being more male subjects.

“Often if I go to schools, and I give talks to kids, and even adults, the first thing I ask is, ‘Describe a scientist for me.’ And what I always hear – and it’s never changed – is an old man with white, frizzy hair, wearing a lab coat, a little bit socially awkward… That suggests that stereotype is still there in society.”

How to change

Vingilis-Jaremko became interested in science at an early age. With a mother as a research scientist and a father as an engineer, questions about how the world worked became a hands-on way of discovering the world around her.

While in school, she was surprised to notice that other girls didn’t like science. But to her, that didn’t seem right. How could they not see how much fun science could be? So, with the help of her mother, she decided to start bringing women scientists into the classroom. It went over well. From there, she started up CAGIS in 1995.

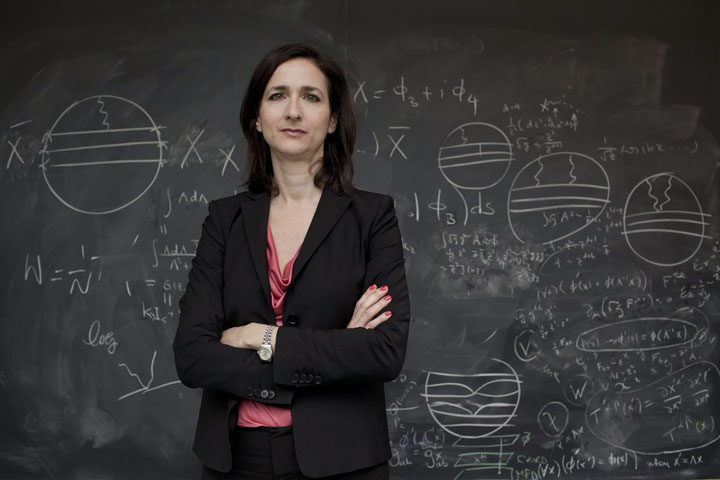

Sara Seager, a Canadian astrophysicist and planetary scientist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), also cites both parental and teacher influence as main drivers of her interest in science. Her father encouraged her to understand how the world around her worked, to ask questions and seek answers.

Then, there was school. There were two teachers in particular who sparked the interest.

“It’s so clear to me that someone needs a special mentor,” Seager said. “So finding that, I think, is very important.”

One of the problems, Seager said, is the perception that “nerdiness” isn’t considered cool, particularly for girls. And she experienced that firsthand. In the early years of high school in Toronto, she hung out with a partying crowd.

But she soon realized that she was going to have to take her studies more seriously if she was to go to university. She became one of the top students. That’s when the partying crowd dropped her. But as a successful astrophysicist and exoplanet hunter, Seager gets the last laugh: She’s successful and doing what she loves.

And that’s another thing she stresses: getting involved in what you love.

“We have to be encouraging the girls that, if there’s a topic you’re interested in, talk to your teachers, so you can get involved,” she said.

READ MORE: LEGO to celebrate women in science

For Maggie, she – like Seager and Vingilis-Jaremko – cites both parental influence and educational influence. And that seems to be the key.

But first there’s the need to break that stereotype of boys being more inclined to be interested in science.

“If there’s a stereotype that’s preventing or shifting a proportion of society away from a particular field, then I think it’s really important to address that,” Vingilis-Jaremko said.

Meanwhile, Maggie will continue to look up at the stars and look forward to her career in sciences, whatever that may be.

Comments