WASHINGTON – The Federal Reserve sketched a dim outlook for the economy Tuesday, suggesting it will remain weak for two more years. As a result, the Fed said it expects to keep its key interest rate near zero through mid-2013.

It’s the first time the Fed has pegged its “exceptionally low” rates to a specific date. The Fed had previously said only that it would keep it key rate at record lows for “an extended period.”

Stocks plunged after the statement was released, but then shot up shortly after. The Dow Jones industrial average sank more than 176 points, then recovered its losses and gained more than 120 points in late-afternoon trading.

Fears of another U.S. recession – and worries about how governments will deal with global debt problems – continue to roil financial markets around the world.

“Crises of confidence do not have silver bullet solutions,” TD Bank senior economist James Marple said in a research note Tuesday.

“The Fed’s action today is unprecedented and will have a modest positive stimulative impact on near-term economic growth.

It “may prove to be more stimulative a little down the road. The market appears to be pricing in a very significant chance of a recession. By removing some uncertainty about future Fed actions, longer-term rates should remain lower for longer.”

The low rates in the United States will put more pressure on the Bank of Canada to keep borrowing costs on hold north of the border as well.

There had been recent speculation that the Canadian central bank would begin raising rates this fall to curb inflationary pressures in the Canadian economy, which has been growing faster than the United States.

However, economists say the recent stock market turmoil and the fears of a double-dip recession in the United States has made it likely that rates won’t rise in Canada until next spring at the earliest.

Get weekly money news

That’s good news for the Canadian housing sector, which has expanded strongly because of low mortgage rates and solid economic growth in recent years.

After the Fed move, many investors sought the safety of long-term Treasurys, whose yields fell as low as 2.07 per cent.

“There is a definite undertone of significant economic concern from the Federal Reserve,” said Greg McBride, an economist with Bankrate.com.

University of Oregon economist Timothy Duy called the move “weak medicine.”

Duy said he wanted to see the Fed commit to buying more Treasury bonds, to try to keep long-term rates down, until the economy improved.

The Fed’s two-year time frame for any rate increase underscored a stark reality: A sluggish economy and painfully high unemployment have become chronic.

The Fed did hold out the promise of further help down the road but did not spell out what else it might do.

The central bank’s decision was approved on a 7-3 vote with three Fed regional bank presidents who have been worried about inflation objecting. It was the first time since November 1992 that as many as three Fed members have dissented from a policy statement.

The Fed used significantly more downbeat language to describe current economic conditions. It said so far this year the economy has grown “considerably slower” than the Fed had expected and that consumer spending “has flattened out.” It also said that temporary factors, such as high energy prices and the Japan crisis, only accounted for “some of the recent weakness” in economic activity.

The more explicit time frame is aimed at calming nervous investors. It offered them a clearer picture of how long they will be able to obtain ultra-cheap credit, and was at least a year longer than many economists had expected.

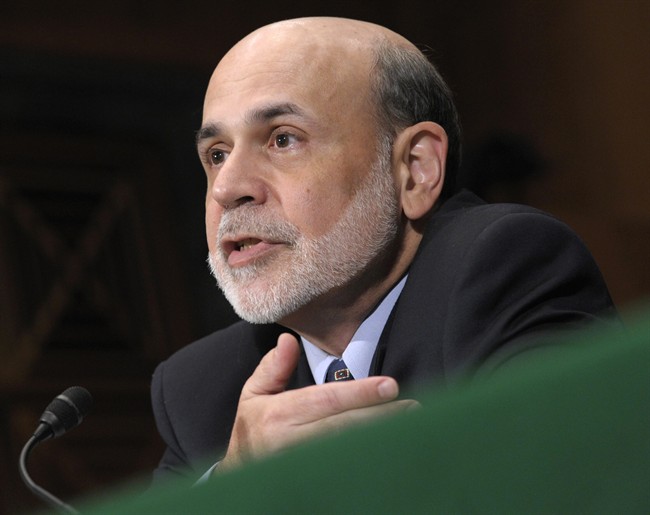

Fed officials met against a backdrop of speculation that they would say or do something new to address a darkening economic picture. The stock market has plunged and government data have signalled a weaker economy in the four weeks since Chairman Ben Bernanke told Congress that the Fed was ready to act if conditions worsened.

The economy grew at an annual rate of just 0.8 per cent in the first six months of the year. Consumers have cut spending for the first time in 20 months. Wages are barely rising. Manufacturing is growing only slightly. And service companies are expanding at the slowest pace in 17 months.

Employers hired more in July than during the previous two months. But the number of jobs added was far fewer than needed to significantly dent the unemployment rate, now at 9.1 per cent. The rate has exceeded 9 per cent in all but two months since the recession officially ended in June 2009.

Fear that another recession is unavoidable, along with worries that Europe may be unable to contain its debt crisis, has rattled stock markets. The Dow Jones industrial average has lost nearly 15 per cent of its value since July 21. On Monday, it fell 634 points – its worst day since 2008 and sixth-worst drop in history.

The tailspin on Wall Street was further fueled by Standard & Poor’s decision to downgrade long-term U.S. debt.

Bernanke didn’t speak publicly after Tuesday’s Fed meeting. The chairman this year made a historic change by scheduling news conferences after four of the Fed’s eight policy meetings each year, but Tuesday’s wasn’t one of them.

Later this month at the Fed’s annual retreat in Jackson Hole, Wyo., Bernanke will likely address the weakening economy, the S&P downgrade and the market turmoil.

Earlier this summer, the Fed ended a $600 billion Treasury bond-buying program. The bond purchases were intended to keep rates low to encourage spending and borrowing and lift stock prices.

With files from The Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.