WATCH: Patrick Cain explains his D-Day poppy maps.

“Take us in as fast as you can,” I ordered. “Don’t slow up, keep us going.”

The landing wasn’t going as Charles Martin expected.

For one thing, rough weather had forced delays which meant the Queen’s Own Rifles would attack in broad daylight, instead of before dawn, as planned. For another, despite the vast invasion fleet around them, their landing craft seemed tiny and alone.

There wasn’t much talk. Earlier we’d worried a little about the choppy, heaving seas. Now, as we came closer, it was the strange silence that gripped us.

Martin was from Dixie, Ont., a farming community on the outskirts of Toronto in what’s now Mississauga. On June 6, 1944, he was a company sergeant major in the Queen’s Own, which had been training for years for this moment. By the time the sun set, 61 men in the battalion would be dead.

Martin survived that day – he wrote about his war experiences in a 1994 book, and died in 1997.

Everyone seemed calm and ready. The boat commander was in charge of this part. He would give our landing order. We waited for it. In just a few inches of water the prow grated on to the beach.

The order rang out: “Down ramp.”

“As usual, it was a disproportionate number of infantry who died,” said historian Mark Zuehlke. “It’s because the fighting was so close and intense. German machine guns were firing right almost at the water line. Our guys were attacking into that, right out of the water.”

The men rose, starboard line turning right, port turning left. I said to Jack, across from me, and to everyone, “Move! Fast! Don’t stop for anything! Go! Go! Go!”

Interactive: Explore the homes of Canada’s D-Day dead in the maps below. Enter your address in the box on the top; double-click to zoom, click and drag to move around. Click a poppy for information about that soldier.

Four regionally recruited infantry battalions led the assault on Juno Beach, the stretch of shoreline assigned to the Canadians: Saskatchewan’s Regina Rifles, the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, Toronto’s Queen’s Own Rifles and the North Shore Regiment from northern New Brunswick.

Get breaking National news

These patterns are visible on the maps, with heavy casualties in all four recruiting areas.

Canadian paratroopers also died as the plan for the airborne assault further inland went wrong, Zuehlke explains.

“The airborne landings went quite badly awry, because as they were coming in the anti-aircraft fire became quite intense, and the pilots quickly lost any idea of where they were, so they were scattered quite badly.”

In the chaos, airborne soldiers landed as individuals instead of part of organized units, often on meadows the Germans had flooded.

A plan to land amphibious tanks on the beach to support the infantry went badly due to rough water.

“The amphibious tanks had these inflatable screens that go up, and that’s what keeps them afloat,” Zuehlke said.

“It’s quite precarious. They had been designed to function on a much calmer sea than was happening. The First Hussars (a tank regiment recruited in London, Ont.) got launched quite a long way off the beach, and they lost a majority of the tanks to sinking. Things did not go the way they were supposed to go.”

Quebec’s Régiment de la Chaudière landed after the first four battalions. The plan was for their soldiers to pass though the first wave and press the assault inland. This happened, but only after a rough landing under heavy fire in which most of their landing craft were sunk by floating German mines.

For all the violence and terror of the day, Zuehlke points out, it could have been far worse. Allied leaders’ deepest fear was of their troops being slaughtered in a bloody failure which would make a future liberation of Europe impossible.

“Winston Churchill had nightmares leading up to D-Day where he would wake up and literally be seeing images of the ocean just covered in bodies floating, and red blood all over it, because he was so afraid that that was what was going to happen,” Zuehlke said. “And it could have been that way.”

U.S. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, who commanded the vast invasion force, prepared an apology for its anticipated failure beforehand.

“My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available,” he wrote. “The troops, the air and the navy did all that bravery and devotion to duty could do. If any blame or fault is attached to the attempt it is mine alone.”

“Various things worked in our favour,” Zuehlke says. “The Germans were not as strong as they could have been and not as well-trained as they could have been.

“It seems silly to say, with that many people dying, that they were lucky, but there was a good element of luck in there.”

How the maps were made

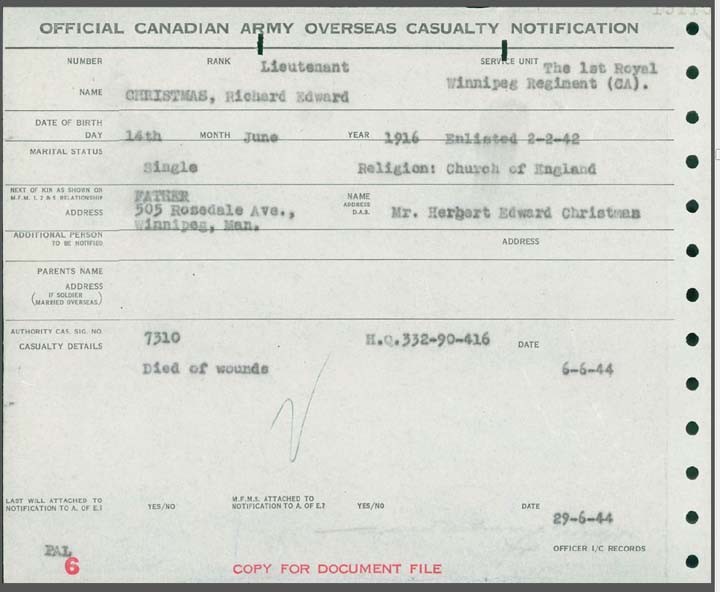

We started with a list of 395 Canadians who died on June 6, 1944 taken from Veterans Affairs Canada’s Virtual War Memorial site. After eliminating some whose deaths were unrelated to D-Day, we were left with 388.

Mostly these were soldiers, with a handful of air crew. We looked for next-of-kin home addresses for all of them, or, failing that, a home town.

Many Toronto soldiers’ home addresses had already been identified through the Poppy File project in 2010. The Veterans Affairs site, contemporary newspaper articles, casualty lists at artillery.net and the Anciens Combattants Québécois site yielded a few more. David Wawryk, the Royal Winnipeg Rifles’ regimental archivist, kindly tracked down two of their soldiers.

Four soldiers’ next-of-kin were in Britain, one in Cuba and one in Maine.

Most came from towns and cities that still exist, but an extinct mining community in B.C. and an extinct farming community in Saskatchewan are represented. One soldier came from Mille Roches, Ont., one of the “lost villages” flooded in the 1950s to build the St. Lawrence Seaway.

In the end, we were able to find at least a home community for all but 15 of them.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.