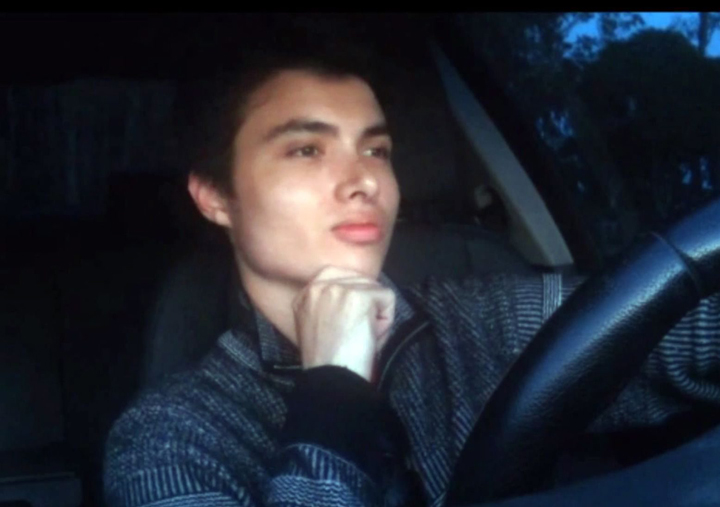

TORONTO – Threatening YouTube videos caused Santa Barbara County police to visit the home of Elliot Rodger about a month before the young man killed six people and then himself. But after speaking with Rodger police concluded he posed no risk, and left.

The 22-year-old wrote in a manifesto later sent to his parents he was relieved his apartment wasn’t searched because deputies would have uncovered the cache of weapons he went on to use in the rampage in Isla Vista, California. Santa Barbara County Sheriff Bill Brown has defended his officers’ actions, saying:

“At the time deputies interacted with him, he was able to convince them that he was okay.”

The case has captured attention north of the border, where police can also face challenges when responding to mental health calls. Police have said they deal increasingly with individuals who have mental illness – the vast majority of whom do not pose a danger to anybody.

Vancouver Police said it “would not be appropriate” to comment on an incident handled by police in another jurisdiction.

Edmonton Police said officers wouldn’t be able to search the apartment but can only look for what is in plain view unless there are “exigent circumstances.” Intervention Services Unit Sergeant David Chow said that could include situations where police had reason to believe a suspect was going to “act out” soon, perhaps following a neighbour dispute or if the suspect made indirect threats and police knew he/she had access to guns, he said.

Chow said Edmonton Police officers have had some mental health training and can apprehend someone if they meet the conditions of the Mental Health Act. That includes anyone suffering from a mental disorder or likely to harm to themselves or others. Police can also take someone to a hospital for psychiatric assessment, where they’ll be in the care of Alberta Health Services.

Calgary Police said a mental health case (though each one is “unique”) would be handled much like any investigation: Gather as much evidence as possible and base decisions on public safety.

Get daily National news

“If we get information from a complainant or a witness that there are concerns of a person’s mental health, then we have to do the investigation to try to speak to these people, speak to anybody that might be able to provide us information,” said Calgary Police Inspector Keith Cain.

“And often that means going to the victim and having dealings with him. …And the officers have to be satisfied that that person is in fact a danger to themselves or others before they can take any action under the Mental Health Act.”

Cain said Rodger’s case appears to have two facets: Mental health concerns, and videos involving threats or indications he’s going to commit a criminal offence. Cain said police would need a search warrant before being able to search a home, but if officers believed a suspect was going to follow through on threats, they could “secure the home” until a warrant was obtained. (This means officers would set up at a number of different points outside the scene to ensure the person in the home doesn’t leave).

Calgary Police attend to mental health calls without doctors or nurses, but base their decision on a combination of evidence gathered from complainants, witnesses, comments and behaviours from the person in question, as well as their police experience and training, Cain said. If they believe someone needs mental health assistance, they can take him or her to hospital; from there, it’ll be doctors who determine what happens next (e.g. released same day or held for a 30-day psychological assessment).

“If the video was evidence that he was planning to kill or threatening to kill people, then we would have to deal with that accordingly. And we would look to arrest that person based upon the evidence that we had that led us to getting the warrant,” Cain said. “But it’s certainly not fair for me, sitting here in Alberta, to comment on California, because I don’t have that information.”

In Toronto, local police expanded their mental health crisis intervention program at the beginning of May to cover all areas of the city.

The Mobile Crisis Intervention Teams pair police officers with mental health crisis nurses working as secondary response squads that move in after police ensure a scene is safe. The teams assess the person in crisis and connect the person to appropriate follow-up services—an important job in a city where police are dispatched to 20,000 calls related to a person in an emotional crisis (according to 2011 data).

READ MORE: Toronto police, hospitals to expand crisis intervention program

“Prior to MCITs, a lot of these people were being picked up and either brought into the hospital or ending up in the justice system, and this is a better way to make sure that whatever services are brought to help people in distress are the best match for whatever their unique situation is,” Toronto East General Hospital CEO Rob Devitt told Global News earlier this month.

On May 8, the Ontario Provincial Police rolled out a program that uses a new form to help officers recognize signs and symptoms of mental illness.

The Brief Mental Health Screener is supposed to teach police when to take someone to hospital based on observations police record in a standardized way – because before, the study found, they didn’t know.

“The reasons why police officers take persons to hospital were not the same as the reasons why persons are subsequently admitted. This suggests the criminal justice, health and mental health systems are not synchronized,” said an explainer of the screener from developer Ron Hoffman.

Dr. John Hirdes, chair of the interRAI Network of Excellence in Mental Health, said Hoffman’s findings suggest the form will help fix the disconnect.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.