Even as the trains start to chug again along Canadian railways, there are fears of another labour dispute among pilots at Air Canada grounding jets across the country in just a few weeks’ time.

It hasn’t just been a summer of strikes and stoppages in Canada: a wave of job actions in recent years has swept across ports in British Columbia, government offices in Ottawa and hospitals in Quebec.

Whether they work on tarmacs, behind desks or in classrooms, Canadians have been taking to the picket lines as negotiations between unions and employers seem to increasingly fall through at the table.

Experts who spoke to Global News say that even as the rising cost of living shows signs of cooling, inflation is still to blame, as workers see their purchasing power eroded and push for better wages in response.

“This is the hangover of inflation,” says David Macdonald, senior economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. “This is workers trying to claw their way back from this huge increase in prices.”

An historic trend

Inflation soared during the COVID-19 pandemic recovery, peaking at 8.1 per cent in June 2022 as Canadians rushed out to spend as travel restrictions lifted and semiconductor shortages drove up prices for goods like new cars.

Statistics Canada says that in 2022, the median after-tax household income fell 3.4 per cent to just over $70,000 as decades-high inflation levels coincided with a dropoff in government support tied to the pandemic.

Get weekly money news

Though inflation has cooled lately, last coming in at 2.5 per cent in July, wage gains tend to lag inflation. For the past 18 months, average annual wage increases have outpaced yearly inflation as the Bank of Canada’s benchmark interest rate rose to cool price pressures.

Some of those pay hikes have come through individual negotiation or changing jobs, while many in unions have been locked out or forced to withhold their labour to make gains at the bargaining table.

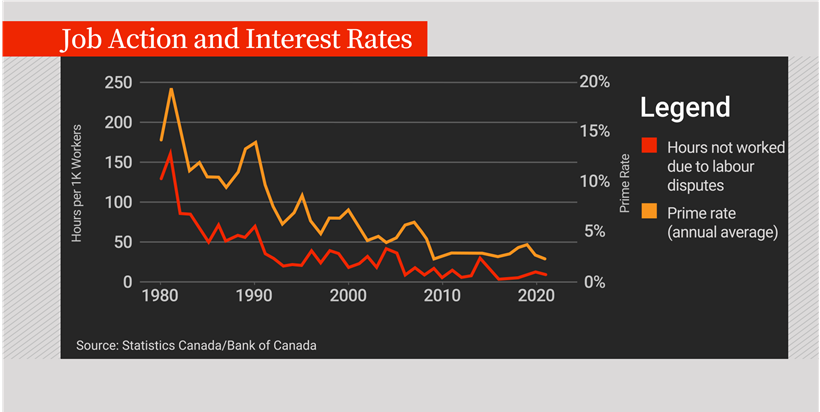

History has shown that both hours lost due to work stoppages and the prime lending rate in Canada tend to rise in response to periods of higher inflation.

Macdonald says wages are typically faster to respond in the private sector. But in a union, collective bargaining sees agreements reset every few years, resulting in more of a lag.

“To get to those higher wages often involves conflict,” he says. “That’s what we’re seeing in several sectors.”

Macdonald says some of the industries prone to disruption include transportation and warehousing — sectors that encompass the recent rail stoppage and last summer’s B.C. ports strike — as well as public administration, health care and education.

Moshe Lander, economist at Concordia University, says that the higher inflation goes, the harder it can be for employers and employees to find higher ground.

In the cast of two per cent inflation in a given year, a worker might seek a raise of three per cent while management might try to keep costs low with a pay hike of one per cent — both offering around 50 per cent above or below the rate of inflation.

But when inflation is closer to eight per cent, Lander explains that either side might typically go as high as 12 per cent or as low as four per cent.

“That leaves a lot more room for negotiation to take place. But that also means there’s a lot more room for negotiations to break down,” he says.

A return to labour unrest

Canada is coming off many years of relatively tame inflation, so it’s no surprise that major labour disruptions were uncommon during that period, Lander argues.

But as inflation reaches levels not seen since the 1980s, he says the response from the labour movement will be more pronounced as well.

Macdonald also argues that labour unions have less power in Canada today than they did in the ’70s and ’80s, which led to them wielding more power in the form of job action.

Certain contractual amendments that would see wages automatically rise in line with the consumer price index are more rare in today’s agreements, Macdonald notes, making the pay reset when a contract expires that much greater.

“Because there isn’t that automatic linking, it means you need much bigger pay increases,” he says. “And often, those are hard for employers to swallow, even if employers have done really well over the last couple of years in terms of major increases in their corporate profits.”

Lander points not to inflation or stagnant wages being the issue, but instead to productivity as the core of the concerns.

Productivity improvements allow Canadian workers to produce more in the same number of hours worked, earning more money for their employer and thereby making it easier for a business to raise wages without feeling as much of a crunch on the bottom line.

Unfortunately, productivity has been flat or declining in Canada as of late. Lander says the kinds of conditions that have precipitated the strikes of the past few years will become all too common if the productivity puzzle can’t be solved.

“There is a consequence here for Canadians then, which is if we can’t figure out how to boost our productivity, then this going forward is going to be a pretty common way of the future that our purchasing power is going to be in permanent decline,” he says.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.