NOTE: The following article contains content that some might find disturbing. Please read at your own discretion.

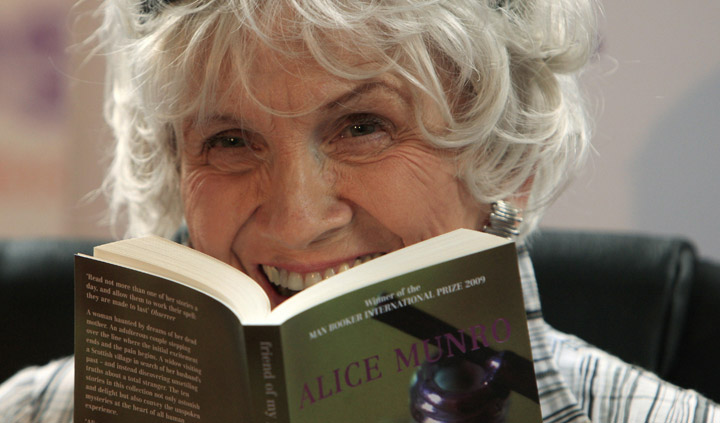

The daughter of celebrated Canadian writer Alice Munro has come forward with a dark secret about her family that is rocking the literary world and re-contextualizing the author’s legacy weeks after her death.

Andrea Robin Skinner, the youngest of Munro’s children, penned a first-person essay in the Toronto Star on Sunday that sheds light on the sexual abuse she suffered at the hands of her stepfather, Gerald Fremlin, Munro’s second husband. Skinner, who was nine years old when the abuse began, writes that her mother knew about it for decades and stayed silent.

Fremlin’s abuse was swept under the rug, Skinner writes. Even when he was eventually charged with indecent assault against her and pleaded guilty in a 2005 trial, her mother remained loyal to her abuser. Munro stayed married to Fremlin until his death in 2013.

Munro died on May 13 at the age of 92. Headlines of her death dominated Canadian news, with outlets hailing her mastery of the short story and praising her intimate portrayals of the lives of women and girls. Now, conversations are taking place about whether the Nobel laureate’s novels deserve space in the bookshelves of the nation.

Skinner’s story

Skinner is the youngest daughter of Munro and her first husband Jim Munro. The pair divorced in 1972 and each went on to remarry: Munro to Fremlin, and Jim to Carole Sabiston, a textile artist.

Skinner mainly lived with her father and stepmother in British Columbia, but spent summers with her mother in Ontario. In 1976, the year Munro and Fremlin were married, Skinner was sexually assaulted by her mother’s new husband.

Munro was away and Skinner, who was nine years old, had asked if she could sleep in Munro’s bed, next to Fremlin’s in the bedroom the couple shared. Fremlin crawled into the bed and molested her as she tried to fall asleep.

Then, Fremlin “tried to get me to hold his penis. My hand kept going limp though as I was pretending very hard that I was asleep,” Skinner told the Star.

Skinner, afraid of the fallout, didn’t tell her mother what happened. When it was time for her to return to British Columbia, Fremlin drove her to the airport by himself and asked the nine-year-old to expose herself to him — she said no — and tell him details about her “sex life.”

Get daily National news

Back at home, Skinner told her stepbrother Andrew what happened and he urged her to go to his mother Carole. Skinner told Carole who then told Skinner’s father Jim. In the end, Jim decided to not tell Munro about Fremlin’s abuse.

“I was relieved at first that my father didn’t tell her what had happened to me… As relieved as I was, my father’s inability to take swift and decisive action to protect me also left me feeling that I no longer truly belonged in either home. I was alone,” Skinner writes in her essay.

Over the next several years, Skinner would return to Ontario each summer. Fremlin made inappropriate jokes, she wrote, “exposed himself during car rides” and talked about his sex life with Munro when he was alone with his stepdaughter. She tried to ignore him.

The abuse stopped when Skinner reached her teenage years and Fremlin lost interest, the Star reports. Munro seemingly remained in the dark until her daughter exposed the truth in a 1992 letter.

Skinner was 25 at the time and struggling with the trauma of her abuse. She had developed an eating disorder and battled insomnia and migraines. She had dropped out of the University of Toronto as a result.

She decided to come clean to her mother about what happened.

“I have been carrying a secret for sixteen years. Gerry abused me sexually when I was 9 years old… I have been afraid all my life that you would blame me for what happened,” she wrote in a letter to her mom.

Skinner’s fears were realized. Instead of being met with sympathy and compassion, Munro painted herself as a victim of infidelity.

“She called my sister Sheila, told her she was leaving Fremlin, and flew to her condo in Comox, B.C. I visited her there and was overwhelmed by her sense of injury to herself. She believed my father had made us keep the secret in order to humiliate her. She then told me about other children Fremlin had ‘friendships’ with, emphasizing her own sense that she, personally, had been betrayed,” Skinner writes.

When Fremlin learned of the letter, he began a campaign to discredit Skinner. In the end, his writings served to expose his crimes, and later helped in prosecuting him for indecent assault.

In a letter written to Jim and Carole, Fremlin wrote: “It is my contention that Andrea invaded my bedroom for sexual adventure. If she were in fact afraid, she could have left at any time. She was sexually receptive and mildly aggressive. While the scene is degenerate, this is indeed Lolita and Humbert. For Andrea to say she was ‘scared’ is simply a lie or latter day invention.”

He referred to her numerous times as a Lolita, and himself as a Humbert Humbert, referring to characters from Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. Fremlin seemed to believe that Skinner, at nine years old, was not a “blameless victim” but a seductress.

Despite Fremlin’s letters, Munro went back to him and for years the family skirted around the topic of abuse. No one in the family spoke of it. No one wanted to tarnish Munro’s rising fame and reputation as a writer.

But in 2002, Skinner became pregnant with twins and the issue could no longer be ignored. She told her mother that Fremlin would never be allowed near her children and confronted Munro with some of the horrible specifics of the abuse she faced as a child.

Three years later, still feeling betrayed and silenced, Skinner went to the police. On March 11, 2005, an 80-year-old Fremlin pleaded guilty to indecent assault for abusing Skinner in 1976. The letters Fremlin wrote were a key piece of evidence.

Fremlin never served jail time. He was placed on probation for two years, ordered to not have contact with Skinner and prohibited from visiting parks or playgrounds. Still, Munro stayed and not much about the family dynamic changed, the Star reports.

“The family went back to socializing with the pedophile,” Skinner’s sister Jenny Munro told the Star. “My mother went on a book tour.”

Fremlin died in 2013, the same year that Munro received the Nobel Prize for Literature. Jenny accepted the award on her mother’s behalf.

Skinner never reconciled with her mother, who died in May this year.

Now, the siblings are standing together, in agreement that Skinner’s story must be told publicly. The Star reports they are worried about the fallout of this revelation, but hope “this might lead to a more robust understanding of her as a writer.”

Already, the impact is being felt — with many Canadians sharing their shock online. It remains to be seen how Munro’s legacy will be affected longterm.

In her essay, Skinner said she hoped that Fremlin’s 2005 conviction would ensure that she never saw “another interview, biography or event that didn’t wrestle with the reality of what had happened to me, and with the fact that my mother, confronted with the truth of what had happened, chose to stay with, and protect, my abuser.”

While that didn’t happen in the aftermath of the 2005 trial, it could certainly be the case now.

If you or someone you know is experiencing abuse or is involved in an abusive situation, please visit the Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime for help. They are also reachable toll-free at 1-877-232-2610.

Comments