Staffers of the Aamjiwnaang First Nation leaving their band office with complaints of headaches, nausea and dizziness.

A family of three rushed to the hospital.

An expectant mother fearing for the well-being of her baby.

These are snapshots of the chaos that has unfolded on this First Nation in southwestern Ontario, located near Sarnia in an area called “Chemical Valley.” The band issued a warning on April 16 after extremely high levels of the cancer-causing chemical benzene were detected in the air.

“I started freaking out,” said Saige Hallet-Plain, 19, who is 30 weeks pregnant. “I don’t know what’s happening to my baby.

“I don’t know if she will be safe, even after she’s born, or if there could be difficulties.”

Hallet-Plain is one of dozens of residents in the small First Nation of 900 people who have reported feeling sick or in some cases needing hospitalization.

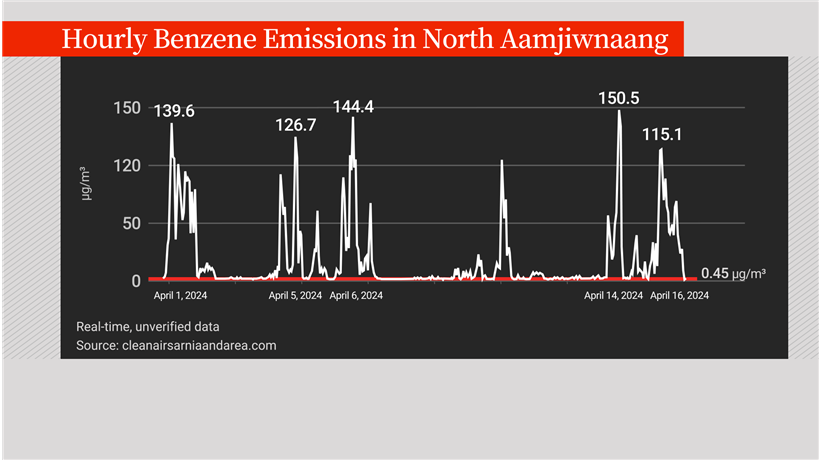

A Global News analysis of air monitoring data from the region shows significant spikes in the weeks and even years before the urgent alert sent on April 16.

While there are many sources of benzene in the area, Aamijwnaang has blamed the toxic air on INEOS Styrolution, a chemical manufacturer, and has called for the government to take action and shut the plant down.

Ontario’s Environment Ministry has set the annual average limit for benzene at 0.45 ug/m3 (micrograms per cubic metre). The province does not regulate the hourly limit. On April 16, the day many residents reportedly felt ill, the benzene levels hit 115 ug/m3 early that morning.

A Global News analysis of air quality data showed spikes in benzene emissions for more than two weeks before the day residents reported feeling sick.

David R. MacDonald, the operations manager and interim site director for INEOS Styrolution, said the company is “carefully reviewing” concerns raised by Aamjiwnaang First Nation regarding benzene readings from the INEOS site.

“The site works closely with the (Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks) to ensure we stay within the prescribed emissions limits,” MacDonald wrote in an email.

Global News reviewed data from the Clean Air Sarnia Area (CASA) website, which monitors air in the region. The data has not yet undergone complete quality control assessments.

Get daily National news

The analysis of data from the monitor indicates that levels of the chemical reached nearly 140 ug/m3 on April 1 in north Aamjiwnaang, with spikes ranging from 126 to 150 ug/m3 between April 5 and April 14.

CASA warns on its website, however, that this data is unverified and should not be used in published documents.

The data also indicates that the First Nation’s exposure to high levels of benzene has been frequent over the past four years.

The north side of the community, which is closest to the chemical plants, has experienced seven to 15 times the 0.45 ug/m3 annual limit every year since 2019, according to an analysis of historical, verified data from the monitor provided by Scott Grant, a retired engineer formerly with Ontario’s Environment Ministry.

Grant explained that, by contrast, Ottawa and Toronto residents are exposed to average annual benzene levels below 0.3 ug/m3.

A Global News investigation in 2017 revealed the serious health effects that residents of Aamjiwnaang First Nation and the city of Sarnia were suffering and possible links to the proximity of refineries and chemical plants in the area known as “Chemical Valley.”

Following the investigation, the Ontario government launched a multi-million-dollar project to examine the possible connection between air pollution from industrial plants and public health.

The findings of that study released by the Ministry of the Environmental last month found that benzene levels in Sarnia are a “concern” in some areas “due to industrial emissions as it could potentially increase the risk of cancer (specifically leukemia).”

Grant, who is now a consultant with the Aamjiwnaang, said the recent elevated readings are 300 times higher than in other communities.

He said the province lacks the regulatory bite to implement fines or any kind of penalties.

“There’s no prosecution. The ministry lacks the capability of enforcement,” Grant said.

“The Ontario government is basically ignoring the concerns of the Aamjiwnaang First Nation.”

A major concern for community members is the way in which toxic air alerts are released, relying on the emitter to report the excess emissions on a kind of honour system..

When an incident occurs at a plant, like a chemical leak, the company is supposed to notify both Sarnia-Lambton Alerts, a notification system run by chemical and oil refining plants in the area, and a community emergency-management co-ordinator, who reports to the City of Sarnia.

Both Sarnia-Lambton Alerts and the city said they did not issue an alert related to toxic air readings because INEOS did not report the problem.

It was Aamjiwnaang that, on Tuesday, issued multiple warnings to its residents about the “dangerously high” levels of benzene in the area.

Over the last five years, the province has issued multiple orders for the company to rein in its benzene emissions. Just last year, the province ordered INEOS to reduce discharges from its tanks, which are just metres from the Aamjiwnaang band office.

The company has never received a fine for the infractions, according to Grant.

Ontario’s Environment Minister Andrea Khanjin said in a statement that the minister has met with Aamjiwnaang Chief Chris Plain and representatives from INEOS following the spike in benzene levels.

“Environmental Compliance Officers have been conducting site visits at INEOS, our mobile air monitoring unit has also been deployed for several days now and remains on site in Sarnia,” a spokesperson said in email.

“We continue to ensure compliance with all past orders made to INEOS, including requirements to install emissions control equipment and undertake additional air monitoring.

“We are working on updates to the benzene technical standards for petrochemical and petroleum facilities, and to strengthen the Environmental Penalties Regulation so that more financial penalties can be imposed.”

Federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault has not yet responded to requests for comment.

The crisis, residents say, continues to put their health at risk.

Christine Rogers was at work Tuesday when she said she became suddenly ill along with her father, Bob, who was working outside down the road from the band office. They and Christine’s daughter were allegedly rushed to hospital by ambulance after experiencing headaches, nausea and dizziness.

“It’s still in my system, I feel it.”

The Rogers family, along with the First Nation’s chief and council, have called for urgent action from all levels of government to shut down the plant.

“Immediate reforms are needed to address the systemic racism which pervades the environmental protection regime and allows industry proponents, such as INEOS, to continue with ‘business as usual,'” the First Nation said in a statement Wednesday.

Christine Rogers said it’s terrifying that Aamjiwnaang was the first to detect the skyrocketing chemical levels and issue an alert.

“We can’t even trust the people who are supposed to be regulating these things,” Rogers said. “Why were they allowed to continue operating at that level when we knew that they were elevated?”

Residents say they are frustrated and furious by the lack of action from the government.

“I’m very angry,” said Christine Rogers. “It’s not OK. None of it is OK.”

— with files from Mike Drolet

Comments