Aylan Couchie is an Anishinaabe artist from Nipissing First Nation in Northern Ontario. She is currently an MFA Candidate at OCAD University where she is pursuing her graduate studies. Her research focuses on Indigenous monument and public art.

When we were children, my sister and I were bussed to and from separate schools.

On the ride home, I would transfer from my bus onto my seven-year-old sister’s where I’d regularly discover her in tears, having been subjected to verbal and physical harassment by teenagers on the same trip. Those days were the first time I’d heard the word “squaw,” and I could never figure out why someone would want to burn wagons.

READ MORE: Is cultural appropriation an act of theft or artistic literary exploration?

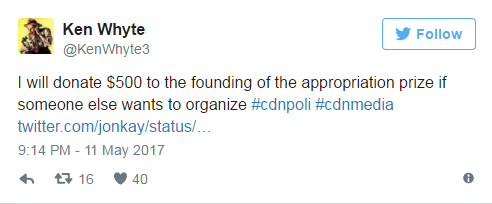

Last week, in the wee hours of the morning, I opened Twitter and was confronted with former National Post editor Ken Whyte’s degrading “Appropriation Prize.”

The way in which he cajoled and cheered on his media cohort as they contributed to his fund, reminded me of how it felt being at the mercy of teenagers on those terrible rides home. This openly demonstrated behaviour, though shocking for some, emboldens others who watch and take cues from what these prominent media figures write.

In light of these events and the outpouring of opinion pieces since, Indigenous folk voicing their concerns on social media have been left open to ridicule by uneducated attitudes towards our rights and thoughts on this matter.

READ MORE: Walrus editor Jonathan Kay resigns amid cultural appropriation controversy

Much has been written (and written well) by my peers on this topic, so instead of re-educating again, I’ve decided to write about what cultural appropriation ISN’T. Cultural appropriation is NOT Indigenous people wearing blue jeans and eating Chinese take-out. Cultural appropriation is NOT Indigenous people driving cars and using computers.

Cultural appropriation is NOT me writing this article in English. No dear naysayers, what that is, in fact, are the effects of colonialism and residential schools — and it shouldn’t fall to us to repeatedly point that out. Reading up on openly accessible educational materials such as the Truth and Conciliation Commission, UNDRIP and the Indian Act could be enlightening for many, including those in the media.

READ MORE: B.C. school panned for having white people in headdresses tell indigenous stories

I see many columnists who are still invoking the name of Amanda PL and her cancelled exhibition in the name of victimhood. As an artist, I applaud the owners of Visions Gallery who responded so quickly to concerns from the arts community.

As gallery owners, they have an ethical and moral responsibility to ensure that they are supporting artists who have not engaged in issues of copyright and plagiarism. Members of the arts community see her work for what it is, inauthentic and dishonest, so why is she still part of the conversation?

READ MORE: CBC editor reassigned from ‘The National’ after cultural appropriation incident

Since Hal Niedzviecki’s editorial writing titled, “Winning the Appropriation Prize” where he opined, “I don’t believe in cultural appropriation,” the Indigenous community has been bombarded with sycophants, who espouse his opinion as fact.

Too often there is no desire to engage with the issue through a realistic context, through the lens of how Indigenous people are treated. The argument boils down to a persistent notion that continuing to exploit Indigenous people is an inherent right. Nothing illustrates this more than souvenir shop displays, where you’ll see dreamcatchers made in China, replicas of totem poles, Inuit inuksuks and sculptures of “Indians” in headdress – the word CANADA embossed or glued onto the front. It’s this continued commodification of our culture that we are loudly halting. Indigenous creatives make works of art about their ways of being, about their lives – including the impacts that colonization has had on themselves and their families.

In fighting against our rights, opponents are simply saying that after colonizing Indigenous people for hundreds of years, settlers want to reserve the right to reward themselves with more. Well, that’s just not going to fly anymore.

“The Mob” as we’ve so affectionately been called, is tired of fabrications such as the ones spewed forth by Senator Lynn Beyak and regurgitated this past weekend by Barbara Kay. To those fighting their battle for “freedom of speech,” the rest of us fight for the dignity and respect of actual humans.

Our voices speak with thoughts mindful of people like Barbara Kentner, who was struck by a trailer hitch thrown from a moving vehicle in Thunder Bay, an incident that’s been called a hate crime.

We are mindful of our children whose lives are impacted by racism, inadequate access to housing, clean water and education. We speak up to break down systemic institutional barriers so that generations to follow will not have to.

We are calling on the media to practice responsibility. Words have consequences; they can inform and misinform readers, some of them parents who pass perspectives onto their children.

The “political correctness” that some people oppose has actual consequences to Indigenous children and communities. In the end, it is us who are left bearing the brunt of irresponsible games and words.

Comments