Two Canadian magazine editors have resigned and a television producer has been reassigned after defending the right of authors and other artists to take inspiration from cultures different than their own.

The phenomenon in question is called cultural appropriation: Inherent in the name is the implication that the act is theft, rather than a literary exploration of a world beyond the writer’s own.

Toronto painter Amanda PL was quite open about her work taking inspiration in both style and subject matter from an Anishnaabe artist. She was honouring that artist, not plagiarizing. But that didn’t stop the Visions Gallery from cancelling the event, capitulating to the mob of people accusing the artist of racism and colonialism.

READ MORE: Let’s start with what cultural appropriation is not

And then came Hal Niedzviecki, the editor of Write — the magazine of the Writers’ Union of Canada (TWUC) — who contended that authors should be not only be allowed, but encouraged, to craft characters across the spectrum of cultures.

“In my opinion, anyone, anywhere, should be encouraged to imagine other peoples, other cultures, other identities,” he said in the editor’s note, for which TWUC has since apologized.

The union apologized for the hurt caused by the piece, and rather ironically said the magazine aims to be “sincerely encouraging to all voices.” Except in apologizing for Niedzviecki’s piece, the union is in effect saying not all voices are welcome.

- What is a halal mortgage? How interest-free home financing works in Canada

- Capital gains changes are ‘really fair,’ Freeland says, as doctors cry foul

- Budget 2024 failed to spark ‘political reboot’ for Liberals, polling suggests

- Peel police chief met Sri Lankan officer a court says ‘participated’ in torture

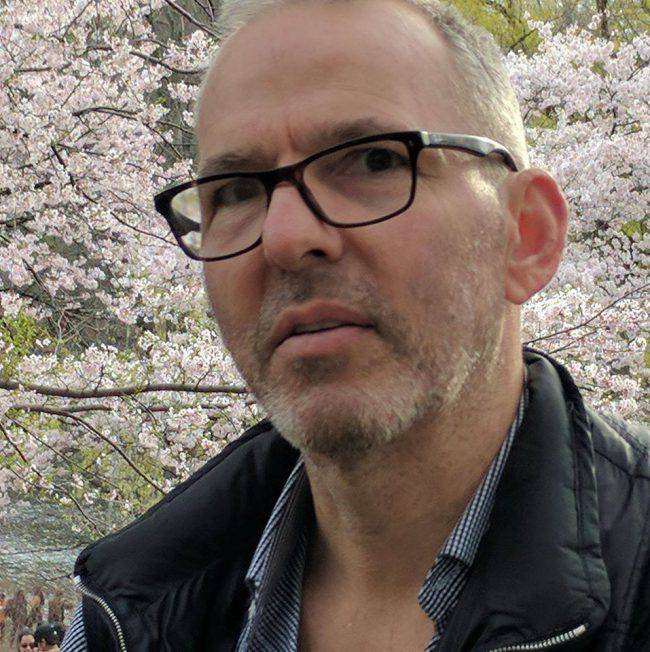

READ MORE: Walrus editor Jonathan Kay resigns amid cultural appropriation controversy

The union’s “equity task force” (the in-house legislator for the aggrieved) called for sensitivity training, “affirmative action hiring” practices, turning over the magazine to editors from indigenous communities for the next three issues, and a paid equity officer who must be “active and respected in anti-oppression cultural movements for at least three years.” Of course, this role has priority for “indigenous writers, racialized writers, writers with disabilities and trans writers.”

Any sensible person would see this response — and the myriad accusations of racism directed towards Niedzviecki — as excessive. Especially since Niedzviecki himself wrote his now-maligned column in the spirit of bridging understanding across cultures.

And then came former Walrus editor-in-chief Jonathan Kay, who critiqued the “mobbing” of Niedzviecki in a tweet, on a CBC panel discussion, and again in a National Post column — the latter of which culminated in his abrupt resignation from the magazine, citing a trend of “self-censorship” that put his Walrus role at odds with his scrappy columnist instincts.

Managing editor Steve Ladurantaye of CBC’s The National was part of a Twitter exchange suggesting an “appropriation prize” — even offering to chip in some money for it — for the best example of appropriation each year. Despite posting a heartfelt series of apology tweets vowing to do better in the future, he was reassigned to another role at CBC.

Days after his resignation, Niedzviecki went on a pandering apology tour, saying the situation “breaks my heart.”

He said on CBC’s The Current that his goal was to “push some buttons within the writing community and make sure we didn’t err so much on the side of caution that we’re no longer able to, say, put a person of colour in a piece of writing.”

If that truly was the intention, he should be declaring victory rather than apologizing. He certainly pushed buttons, and proved that the writers’ community is willing to stomp on the value of literary freedom.

Whether a white author should craft a black or aboriginal character is secondary to the far more important point, which is that a writer can create whatever work he or she wants to, for whatever reason. That’s what art is. That’s what freedom of speech is.

There is a fundamental difference, I admit, between censorship imposed by the state — the most egregious kind — and censorship that is self-imposed because of a political or ideological climate, but the result is the same. In both cases, ideas and speech are stifled, meaning thought itself is subverted.

Speaking at an academic freedom conference at Western University in London, Ont. last weekend, academic firebrand Jordan Peterson labelled free speech “the process through which ideas are generated.”

We often view speech as the way ideas are shared, but that process — the dialogue of exchanging ideas — is how new ideas, and by extension new truths, emerge. In the fiction world, it’s how new perspectives and stories emerge.

When bestselling author Lionel Shriver took aim at cultural appropriation during a literary conference last September, she faced many of the same accusations of racism and privilege directed towards the players in the TWUC kerfuffle.

One of the most important points she raised was how much great work simply wouldn’t exist if not for the creators taking influence from people unlike them.

She cited Graham Greene, Malcolm Lowry, Matthew Kneale, and Maria McCann — all writers whose work involved using voices of people of different races, background, and sexual orientations.

To dogmatically impose the cliche “write what you know” on writers would make literature very boring. Whether you’re reading a book about wizardry, spies or bank robbers, there’s a high likelihood that the author wrote it from a place outside of their own identity.

We need to restart viewing that as art, not theft.

Andrew Lawton is host of The Andrew Lawton Show on AM980 London and a commentator for Global News.

Comments