WATCH: 5Gyres: Plastic pollution in the world’s oceans

TORONTO – Over the Christmas holidays, many of us will be unwrapping presents, cutting open packages and tossing aside thick blister packs.

Where will that all end up?

Sadly, a lot of it may end up in our oceans.

READ MORE: Microplastics building up in water, sediment, ocean life: Dalhousie research

Our oceans make up more than 70 per cent of our planet — and they are choking on our waste.

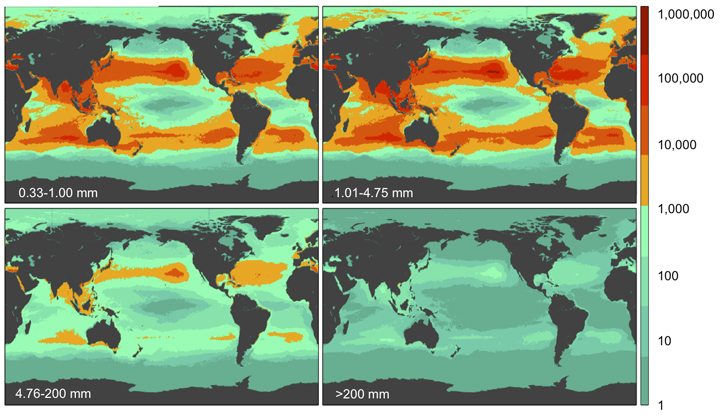

Last week, a study by the 5 Gyres Institute, was published in the online journal PLOS One. It concluded that about 270,000 tons of plastics are floating around our oceans. All of that is broken into 5 trillion pieces, and can be found primarily in gyres, areas of large rotating ocean currents.

There are five major gyres on Earth: the Indian Ocean Gyre, North Atlantic Gyre, South Atlantic Gyre, North Pacific Gyre and the South Pacific Gyre.

READ MORE: Study finds more than 260,000 tons of plastic floating in the ocean

“Of the 5.25 trillion particles, over 90 per cent were micro plastics. Those small, small pieces, smaller than a grain of rice,” said Marcus Eriksen, an environmental scientist and research director of 5 Gyres.

And the fact that the plastic is broken up into so many pieces is bad news for anybody who thinks they can easily go out and collect it, said Eriksen.

“You’ve got these trillions of particles that are dispersed over two-thirds of the planet’s surface, so recovery of most plastics at sea is really unrealistic.”

While a lot of the plastics out there is lost fishing gear, the packaging we as consumers may unthinkingly toss in the trash also plays a part.

“I challenge the producers and manufacturers of plastics,” Eriksen said. “If you can’t design it 100 per cent recovery, then design 100 per cent environmental harmlessness.”

What it means

Having fish for dinner? You might want to think about where that fish was caught.

“The concern now is that these plastics are accumulating in these gyres and they’re found to be more persistent in the marine environment,” said Peter Wells, adjunct professor at the Faculty of Science at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia. “They break down into micro-particles…and there’s concern about food chain uptake.”

Fish in our oceans are eating some of that plastic, material that is very good at absorbing some dangerous toxins like DDT and PCBs.

Wells, who is also a senior research fellow at the International Ocean Institute, is concerned about food chain impacts as a whole. It’s not just about the fish we’re consuming. It’s about cetaceans (whales), birds and turtles. And the location of the plastic waste couldn’t be worse.

“Gyres attract algae, and they attract all sorts of organisms that feed there,” he said. “So it seems like the most productive areas biologically and these areas where these plastics are accumulating are occurring together.”

Wells knows that for most people who live inland, the health of our oceans may not be on their radar. But it should be.

“If people became aware that [what] happens on land does affect the oceans and the health of the oceans that we’re so dependent upon, then maybe they’d make that connection so when they’re putting something out to recycle, they’re protecting the ocean.”

Looking to the future

On whom is the onus to reduce pollution: Consumers? Manufacturers? Municipalities?

James Downham, president and CEO of PAC, Packaging Consortium, which works with supply chains and manufacturers on packaging, said that the industry knows of the need to reduce packaging and is taking steps to that end. PAC created an initiative called PAC NEXT whose mandate is to create “a world without packaging waste.”

Manufacturers are taking a serious look at their “end-of-life” packaging, Downham said. As an example, he noted Coca-Cola’s PlantBottle, the first recyclable plastic bottle that is made from plants.

Then there’s the case of excessive packaging. And it seems that more and more people are taking note.

It’s not that food doesn’t need packaging. A recent study by the World Resources Institute and the United Nations Food Programme found that every year consumers in industrialized countries wasted about 222 million tons of food. In North America, more than 30 per cent of the food supply is wasted.

So it’s not about not needing packaging, it’s about not over-packaging.

While many people turn to the toy industry as an example of excessive packaging, Dunham said that it doesn’t all lie with them.

“Is there work needed to be done, absolutely, but if you look at the bulk of packaging, 70 per cent of all packaging go into food and beverage…so the packaging minimization discussion is being replaced by packaging optimization.”

The key is finding a balance between minimizing packaging while at the same time protecting investment. A $3,000 television can’t come in a flimsy box: both the consumer and the manufacturer want to ensure good delivery of the product. And a product that ends up broken and has to be returned creates a larger carbon footprint, Downham said.

And then there’s the need to protect items — such as small USB sticks — from theft.

READ MORE: Plastic Bank turns plastic from B.C. shorelines into new packaging

Krista Friesen, vice president of sustainability at the Canadian Plastics Industry Association, said that recycling is a large focus of their organization.

“We do a lot of work with municipalities across Canada,” she said. And that involves trying to get as much different types of plastic as they can into recycling bins.

She notes that plastic is much more prevalent than it was years ago. Where baby food was once put into glass jars, they are now in plastic bags. Pop bottles that used to be glass are now plastic.

“The more we can put in there, the better it is,” Friesen said. “And we’re seeing better and better success.”

And even if industry and municipalities do their part to ensure that either the plastics and waste is all recyclable, if people don’t put it in their Blue Boxes, it won’t make a difference.

Though people have more incentive to return their beer and wine bottles, nothing like that has been done here in Canada or the United States for plastic, Eriksen noted.

Not so in Germany, which has the Pfand system, where consumers are encouraged to bring back their plastic bottles for a return. And that’s part of reducing plastic waste, Eriksen said: incentives. These could also work for the lost fishing nets that litter the oceans.

The solution to saving our oceans from being clogged up with plastics and other waste is a cumulative effort.

“The major thing to consider is human behaviour,” Friesen said. “You can build something that’s 100 per cent recyclable and it makes into the ground, then it goes into the wind.”

Comments