Hamilton public health (HPH) confirmed on Thursday a pair of bats recently tested positive for rabies, the first cases since last summer.

The city says, so far, there have been no reported interactions with humans since a resident was bit early last year.

Health officials continue to advise Hamiltonians the city is still in a rabies outbreak, which started in 2016 primarily due to the discovery of at least 200 positive cases that year including 123 raccoons and 73 skunks.

Most cases over the last eight years have involved raccoons, accounting for 215 discoveries in all.

The overall risk for human infections from bats is low with only 13 confirmations in tests since 2016.

Despite going years without a positive raccoon rabies case, HPH supervisor Jane Murrell says they haven’t shaken off outbreak status due to incidents in neighbouring municipalities.

“The problem is Niagara region is still having some positives and we are within 50 kilometers,” Murrell explained.

Rabies is transmitted through the saliva of an infected animal — usually through a bite, but can also enter the body upon contact, through scratches, open wounds, or mucous membranes of the mouth, nose and eyes.

Get weekly health news

Murrell says the easiest way to eliminate the risk of contracting rabies is to avoid contact with animals that carry it, like the aforementioned bats, raccoons and skunks.

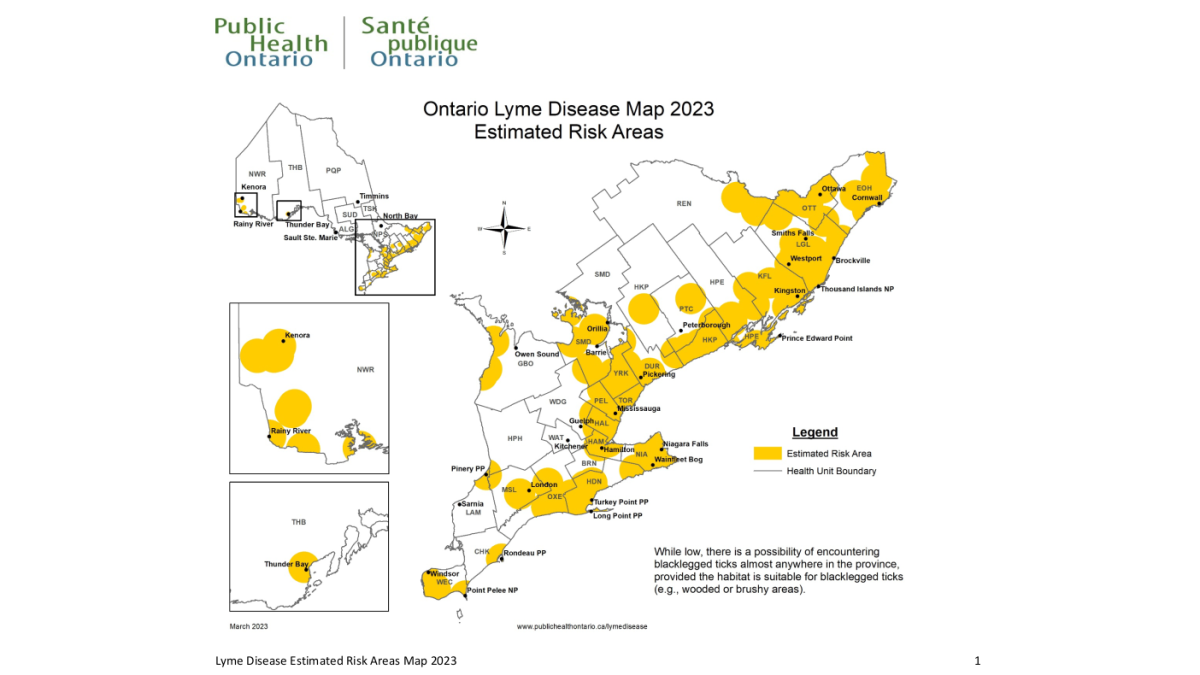

Hamilton included in Ontario’s ‘estimated risk areas’ for Lyme disease

Hamilton continues to be considered a risk area for black-legged ticks and has the potential for residents to contract Lyme disease.

Public Health Ontario has once again included the city on its latest map demonstrating the estimated risk areas for the affliction.

Murrell says despite the designation, the true risk of infection to residents is very low.

The Ontario Lyme Disease Map: Estimated Risk Areas is updated annually. It provides information to assist public health professionals and clinicians in their management of Lyme disease.

“There is potential for some of those ticks to carry the bacteria that causes Lyme disease but not all black-legged ticks carry that bacteria,” Murrell said.

“So the majority of our ticks in the city are still brown-legged dog ticks, which don’t carry Lyme.”

Hamilton hit a ten-year high in 2021 for Lyme disease cases acquired locally with 27 reported to HPH.

It’s a bump of more than 20 cases compared to the previous year (2020) when HPH had just six cases in the city.

Between 2013 and 2022, the city has been averaging just over two cases per year.

Public health is suggesting caution when removing a tick suggesting tweezers and grasping the bug as close to the skin as possible and pulling it straight out, gently but firmly.

Squeezing a tick should be avoided as it can cause secretions that can lead to Lyme disease to escape into a person’s body.

Lyme disease is caused by a bacterium called Borrelia burgdorferi, which is spread through the bite of infected black-legged ticks, according to Public Health Canada.

Typically, infected black-legged ticks need to be attached for at least 24 to 36 hours in order to transmit the bacteria that causes Lyme disease.

Symptoms can take anywhere from a few days to four weeks to appear. They include fever, headaches, tiredness and a skin rash at the bite location.

If untreated, the more severe scenarios include joint pain, severe headaches with neck stiffness or heart palpitations.

Comments