Pow Wows are a celebration of Indigenous culture, open to anyone who wants to come and witness the drumming and dancing.

While they were once banned throughout the country, they’ve made a comeback in various ways and are growing in popularity.

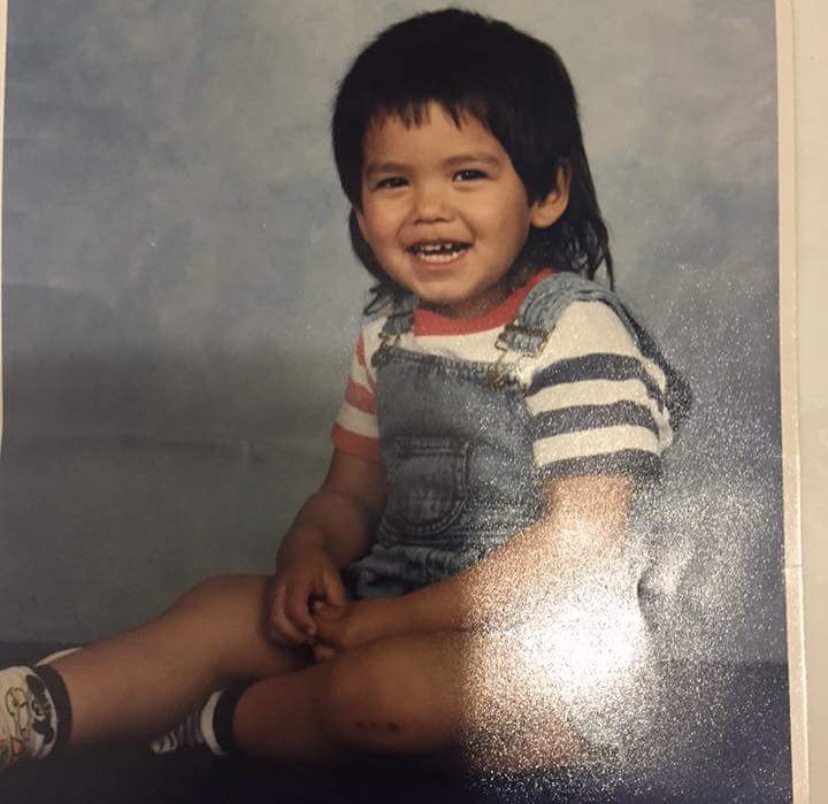

“It’s given me freedom of expression, it’s given me a sense of who I am and it’s allowed me to reconnect,” Ktunaxa Nation’s Peter White (kanǂupqa kȼiǂmiyit) told Global News.

His name is Peter White, but he goes by Peter “Not So” White.

“There’s a play on words with that, that my last name is White and I’m not white,” he said.

He is making a name for himself as an inspirational Indigenous dancer by using social media to encourage connection to culture and raise awareness about the impacts of systemic oppression.

The inter-generational survivor says he was adopted at birth into a non-Indigenous family because his parents — struggling from the effects of the residential school system — couldn’t care for him.

“Residential schools have really affected me and I didn’t even realize how much until recently in doing my own trauma healing and getting to know where I come from … that’s how much residential schools have affected me, that 10 years ago I was a totally different person than who I am today,” Peter said.

In his teens, he grappled with alcohol abuse and homelessness. He says he tried quitting drinking nearly a dozen times and it wasn’t until he was told he had a cancerous tumour on his right foot that he took to dancing.

“I started going to local pows on the weekends for something to do and to keep me sober,” he said.

Get daily National news

While it was the cancer that got him started, he says it’s the power of Pow Wow that’s created the path for his healing and being able to help others.

“It’s a celebration of life, basically that’s what Pow Wow is … it’s coming together and celebrating. It’s pretty powerful because these things were banned for decades… our ancestors fought to keep them alive.”

He has been sober for nearly a decade and continues to motivate others to lead healthy lives, seek professional help to cope with trauma and connect with culture. He’s been asked to teach dance and be a judge at Pow Wow events.

“All Indigenous communities have their own way of dancing… it’s a good way to connect, to get the younger ones involved, even the older ones, it’s a stepping stone to get back into learning culture and I think that’s what Pow Wow has done for me,” he said.

Even then, as Pow Wows became virtual during the pandemic, forcing him out of his small Burnaby apartment and into public places to put on his regalia and dance, he says, at first he felt ashamed.

“It comes from the inter-generational traumas, the shame of being Indigenous, the shame of the things that happened in these schools and the shame of our culture having to be hidden for so long,” Peter said.

His ancestors became prisoners of the “potlatch ban.” The law, lifted in 1951, made it a crime to engage in or assist with cultural dance.

“I feel happy that I have the freedom that my ancestors didn’t have to wear my regalia in public, to have long hair, to do these things that weren’t able to happen for my ancestors,” he said.

The legacy is many to this day either don’t know how to dance or are too traumatized to try. It’s something Chilliwack Secondary School Indigenous Enhancement Teacher Rick Joe is trying to change in part by introducing Pow Wow’s to schools with this year marking the first reconciliation-focused event.

“It’s providing an opportunity for Indigenous families to practice their culture and it’s also the non-Indigenous community to come in and witness that. So that’s the reconciliation, it’s all of us together doing something,” Joe said.

With $20,000 in funding, half from both the City of Chilliwack and the Chilliwack School District, and the other half from Heritage Canada, he says he’s making it happen because he sees the positive impact it’s having on students. But it hasn’t been easy, Joe said.

“It’s difficult in public education to create that safe space. I know it’s important. I’ve been doing it since I was in grade 11 in 1987, trying to organize events when I was in school and university,” he said.

Joe says his hope is to ensure students today have support he never did when he was their age.

“I never felt safe, never felt belonging when I was in school and that’s how I’ve been all my life, I saw something that wasn’t right and I wanted to try and make it right,” he said.

“Making an effort to provide a space for people to learn and having that Pow Wow is going to open the doors for the whole community.”

Both he and Peter are part of a large and growing wave of people once again taking pride in these sacred cultural practices the institutions of assimilation tried to erase.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.