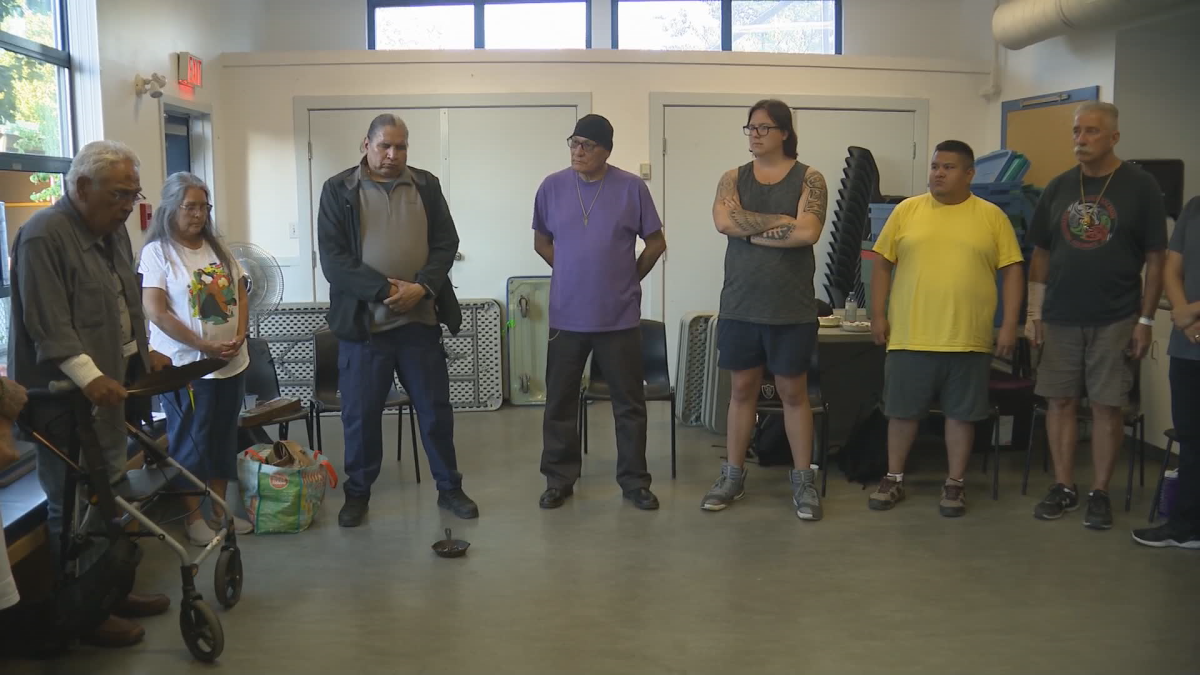

They begin each Monday night with a meal. They then smudge and pray before the real work — the difficult emotional work — is done. They call themselves warriors and the enemy they battle each week is tough. It’s one that’s torn apart families, traumatized kids, and contributed to an epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

These warriors are fighting to heal the trauma within themselves.

“This to me is a solution to the problem of violence,” says Joyce Fossella, executive director of the Vancouver-based Warriors Against Violence Society.

“We do it in a way that’s cultural and it’s with our own way of healing practices as Indigenous people. It works.”

There were many men around the healing circle on the day a Global News camera is allowed inside, but on Mondays, women and gender-fluid individuals take part, too. Almost everyone here has been a victim of violence and abuse but many admit to becoming abusers themselves.

Read more: Brothers mourn slain sister, a counsellor ‘trying to make a difference’ in James Smith Cree Nation

“I don’t know why it’s always the ones that we love or that love us that we always hurt,” says one participant when the Eagle feather reaches his grasp. He’s emotional but tears are encouraged in this circle.

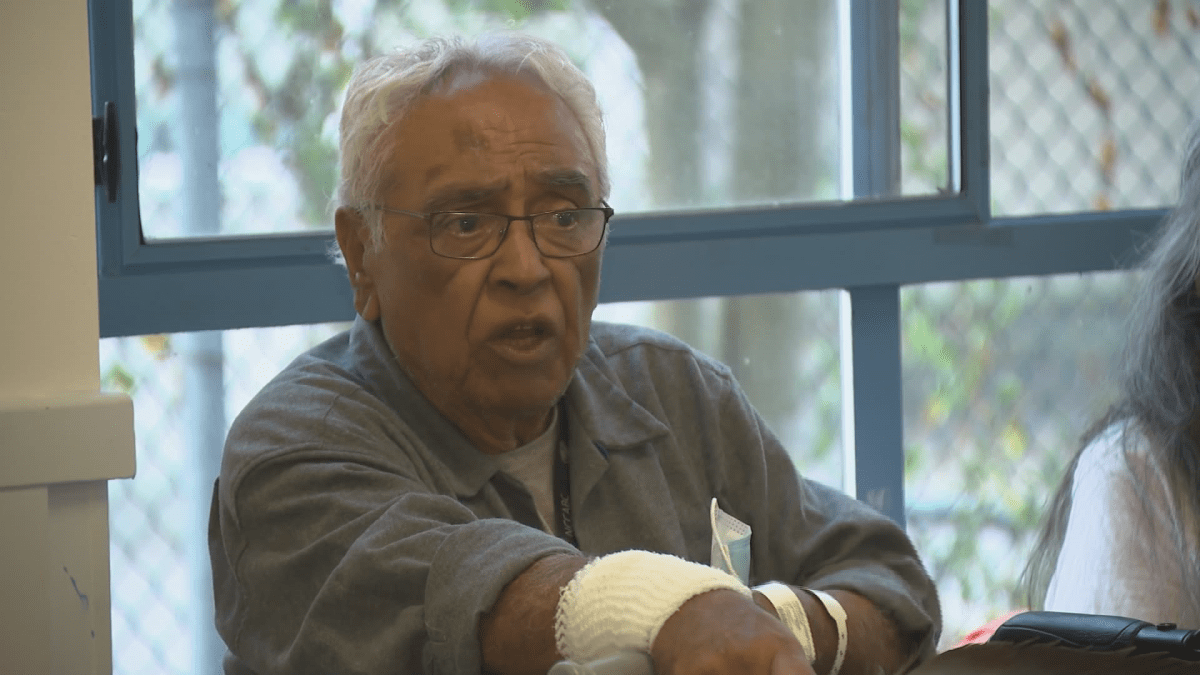

Facilitator and group co-founder Joe Fossella knows showing emotion isn’t something many Indigenous people were raised to do.

“Feelings and emotions (we) could not express, we were told to, ‘shut up,’ ‘I’ll give you something to cry about,’ so we learn to muffle ourselves,” Fosella tells the group as the session begins. “Packing that hurt and pain around for so long instead of being able to (say), ‘I love you. I’m scared. I’m afraid.’ It comes out as anger. That’s what I lived.”

“We’re here to share our own feelings and emotions that we were never able to share when we were younger,” he says as he passes the Eagle Feather around the circle.

Families say James Smith Cree Nation tragedy linked to intergenerational trauma

Get daily National news

A day after the bodies of 10 people were found stabbed to death on the James Smith Cree Nation and the nearby community of Weldon, Sask., the brother of one of the victim’s spoke to the media.

“The battle we’re fighting here is with alcoholism and drug use and even that is just a symptom of the residential school syndrome,” said Darryl Burns.

He and his sister, Gloria, had been addiction counselors in the community. After Gloria was killed responding to a crisis call, Darryl resigned from his position.

“These two young men that took so many lives, they were products of residential schools, they had that anger,” he said.

“When you have all that anger carrying inside of you and you’re not dealing with it, you mix addictions in there, it’s going to come out. We need to deal with this.”

Read more: EXCLUSIVE — Saskatchewan stabbing suspect’s wife says she called RCMP 24 hours before murders

RCMP charged Damien and Myles Sanderson with several counts of murder and attempted murder in connection with the massacre. Damien Sanderson’s body was found on September 5, while Myles Sanderson died two days later after being taken into police custody.

Indigenous communities experience high rates of violence

Lawyer and trauma educator, Karen Snowshoe says the killings on James Smith Cree Nation have hit many indigenous communities hard.

“That (was) not an isolated event,” said the Gwizhii Institute of Learning founder. “That event was highly triggering for probably every indigenous person across the lands.”

Snowshoe says the reason Indigenous communities experience a disproportionately high rate of violence compared to the broader community is linked to the violence and abuse inflicted upon several generations of Indigenous children at residential schools.

“That translated into indirect impacts on the community and generational trauma which we’re now seeing passed to fourth and fifth generations.”

It’s a cycle that participants of the Warriors Against Violence healing circle are determined to break.

“I’m the first person in my family to not go to residential school,” a young man says when it’s his turn to share. He says this is his second session but his first time speaking to the group.

“My grandmother, my mother (attended). I also want to be the first one in my family to stop these generational trauma and abuses and whatnot but it’s hard. I have suffered abuse, too.”

But changes and healing are possible. Joyce Fossella says she’s seen it happen many times.

“I see the impact of this work. I can see these families out there — they are very productive in the community, they are raising their children,” she says.

“Some of them who had children apprehended have all of their children back and they’re back to their family unit and are happy.”

More support needed

Participants are often referred to the program by the justice system, police, parole officers, and even the courts. Over the years, Fossella says, Indigenous communities outside of Vancouver have sought help from the organization as well.

“We’ve had so many calls from all over including Hawaii, all over the United States and across Canada, saying, ‘Is there a program like that for us?’ And we had to say, unfortunately, no,” Fossella says.

Still, the group is doing as much as it can in working to train facilitators from other parts of the country so that the Warriors Against Violence program can be replicated.

“It doesn’t have to be exactly the same, because First Nations all have different cultures, they have different ways,” Fossella says. ” (Communities) need to make it be something they’re comfortable with.”

For healing circle participant ‘Jimi’, a residential school survivor now sober for over 30 years, talking in any capacity is key.

“To me, this program is a lifesaver,” he says, though he knows not everyone struggling may have access to this kind of support.

“Just find somebody to talk to, that’s very important. Talk to the elders in your community, and let them know. Don’t let it get to the point where it did in Saskatchewan, where everything just erupts.”

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.