Canada’s headline inflation rate is widely expected to slow again when the latest consumer price data for August is released on Tuesday, but economists say it’s the underlying “core inflation” figures that the Bank of Canada will be paying close attention to when figuring out how high interest rates will have to go.

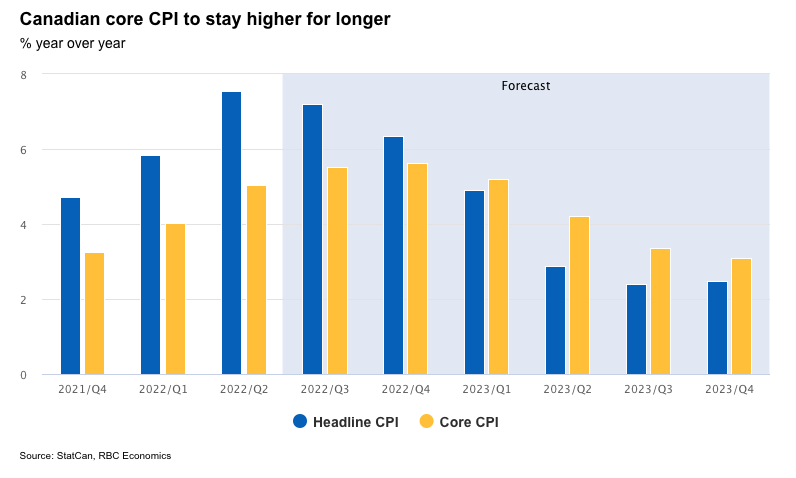

Analysts polled last week by Reuters are projecting Statistics Canada’s consumer price index to cool to an annual rate of 7.3 per cent in August, edging down from the 7.6 per cent seen in July and June’s possible peak of 8.1 per cent.

Economists who spoke to Global News this week agree this figure, routinely called “headline” inflation, is likely to drop as gasoline prices continued their downward trends through last month.

But a Royal Bank of Canada report released on Friday projects that while the headline figure may have already peaked, so-called “core inflation” has not.

This figure, which in Canada is typically estimated through an average of three separate metrics, hit an all-time high of 5.3 per cent in July even as overall CPI slowed. RBC estimates core inflation won’t peak until sometime in the fourth quarter of the year.

What is 'core inflation'?

RBC assistant chief economist Nathan Janzen, who co-authored last week’s report with Claire Fan, says the core inflation measures are meant to provide a “better gauge” of “persistent, underlying” price pressures.

It’s calculated differently across the world, but in general the metric strips out “volatile” items such as energy and food prices to provide a more reliable, long-term view of where inflation is heading.

Get weekly money news

Because food and fuel are routinely subject to global price pressures — the war in Ukraine and global supply chain kinks tied to the COVID-19 pandemic are a couple of timely examples — they aren’t affected much by the Bank of Canada’s interest rate hikes.

Core inflation metrics that remove these items tend to be a better gauge of domestic demand — a price pressure that the central bank’s policy rate does have an impact on, Janzen says.

“Even as some of these … globally driven price pressures have started to ease as gasoline prices have fallen, those domestic pressures have been accelerating and that really is the kind of inflation that is clearly the domestic central bank’s problem,” he says.

“Those core measures are meant to be a better gauge of where inflation is going than the headline price index is. If you see them tick higher, it sends a message that they do need to do more to cool off demand.”

If inflation were solely caused by international factors, the Bank of Canada wouldn’t be forced to raise rates as high to tamp down inflation, says Benjamin Reitzes, BMO’s managing director of Canadian rates and macro strategist.

But the “breadth” and “depth” of inflationary pressures at home is “unprecedented” in the last 20 years, he tells Global News.

He points to a strong national economy, which the Bank of Canada says is running “above capacity,” as driving demand for spending.

Janzen notes that much of the demand fuelling core inflation is currently in services. Canadians had two-plus years of pent-up demand for travel and other activities and are using their banked savings now, even as price pressures are high, he says.

What does core inflation mean for rate hikes? A recession?

The Bank of Canada will have two more opportunities to take the temperature of core inflation before its next interest rate decision on Oct. 26.

Some big-bank economists, including those at BMO and RBC, are now expecting the benchmark rate to hit four per cent by the end of 2022, up from today’s 3.25 per cent.

Reitzes says a pair of hot core inflation readings will fuel the fire for another supersized rate hike next month.

“If inflation is up hotter than expected, then that puts another very aggressive rate hike on the table. They could very well go another 75 basis points,” he says.

BMO is not currently forecasting a recession in Canada, but Reitzes notes the “odds are growing.” If the central bank’s interest rates end up needing to rise above the four per cent bar, the odds of tipping the Canadian economy into a recession probably rise above 50 per cent, he says.

“I wouldn’t say it’s a done deal at this point, but with every strong inflation print that goes by this, the odds of a recession do increase.”

RBC, on the other hand, is calling for a “mild” but “short-lived” recession in early 2023.

Janzen notes that the issue with interest rate hikes is that they work on a lag, and the Bank of Canada likely won’t know whether it’s raised rates enough to cool inflation until six months to a year after the fact.

“That does raise the risk that they’ll need to err on the side of hiking too much in the near-term and push the economy into at least a moderate downturn next year,” he says.

— with files from Reuters

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.