When a call came in to inform Ivor Wayne Burns that police had found the body of one of the men who allegedly killed his sister, his reaction was muted.

“Oh, really?” Ivor replied curiously, standing on the side of the road outside the James Smith Cree Nation boundary in front of a couple of journalists. “That’s interesting.”

His brother, Darryl, who arrived soon after to hear the news, was more forthright. “(I feel) a sense of relief that he’s found — that maybe now his suffering is done and his sorrow is no longer in him,” he said, after taking a deep breath.

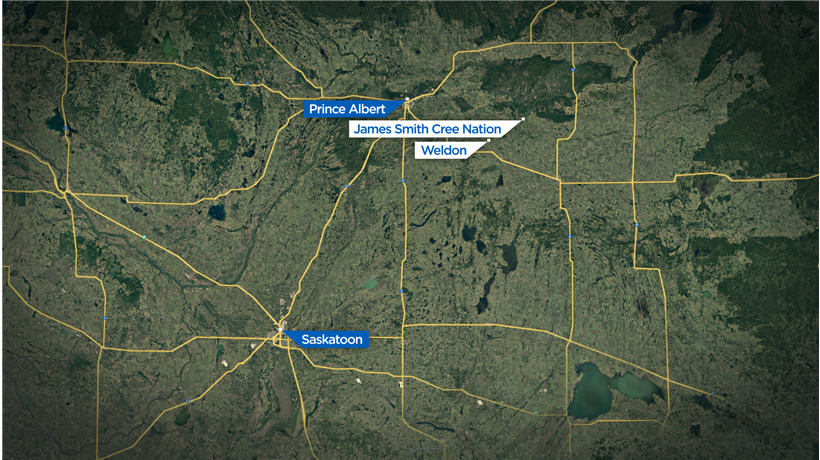

The Burns siblings were each involved in the health and wellness sector in the James Smith Cree Nation. On Sunday, 11 people died and 19 more were injured after a series of stabbings that took place on the First Nation’s land and in the village of Weldon. The Burns’ sister, Gloria, a 62-year-old addictions counsellor who worked for the National Native Alcohol and Drug Abuse Program, was one of the dead.

Darryl was also an addictions counsellor until Monday, when he quit his job after his sister’s death, frustrated by the lack of social support and rampant drug and alcohol abuse on the reserve.

The RCMP had initially embarked on a multi-province manhunt to find two brothers — Damien and Myles Sanderson — in relation to the murders. However, Damien’s body was found on Monday morning at a location on the James Smith reserve with injuries not believed to be self-inflicted. Officials warned that his brother, Myles Sanderson, may be injured but is still considered armed and dangerous and faces multiple charges in connection with the attacks.

According to documents obtained by Global News from the Parole Board of Canada in relation to Myles’ statutory release from prison in February, the suspect had 59 adult criminal convictions and a history of drug and alcohol abuse. The 31-year-old started smoking marijuana at age 12 and using cocaine at age 14, documents show.

On Monday afternoon, as Saskatchewan RCMP announced the discovery of Damien’s body, the Burns brothers had travelled outside the First Nation’s boundary to speak to Global News about their sister.

“We have a story and we want to tell it,” Ivor said emphatically.

Darryl disagreed with a blanket media ban set by his band, which also prevents reporters from being on reserve land — so much that he also quit his job on Monday morning, mere hours after his sister was murdered.

“We’re in a crisis and we need people to understand that people here are hurting,” he told Global News.

“I went into the band meeting this morning and spoke my mind. I’m not going to be quiet. I don’t think the band is doing enough.”

Gloria’s Red Road

Gloria Burns had been an addictions counsellor for about 20 years, her brothers said. She had four adopted sons — nephews she had taken in when their mother died when they were younger — and had lived a hard life before finally finding peace through her career.

“She devoted her life to helping people. She grew up in this community, and she had battled with addiction. She battled with a whole bunch of issues in her life before she started working in the field,” Darryl said.

Get breaking National news

Ivor spoke proudly of his sister’s journey on her “red road,” which means living life with purpose on a path to positive change. Several times he recalled the impact she had had on her community. He said she had “suffered but had found the teachings she was searching for.”

Wearing a bright blue T-shirt emblazoned with the logo of the Elite Indian Relay Association, Ivor spoke passionately about his sister and the community tragedy as RCMP cars streamed into the reserve.

James Smith Cree Nation has a population of about 3,400, while the on-reserve population is estimated to be about 1,900. The area is a sparse stretch of arid land and wheat fields, bisected by gravel roads.

It’s a small reserve where “everyone knows everyone,” Ivor said, which makes the situation all the more tragic.

The day Gloria died, she had been dispatched on a crisis call as a first responder. The Burns brothers did not say where on the reserve her body was found, but said she was discovered alongside another two bodies, that of her friend and a young boy.

“We worked on the same team and it was her turn to be on call. Anyone could have taken that call,” Darryl said, his voice breaking.

The community has been left in total chaos after the tragedy, Ivor said — even more so, considering the Sanderson brothers had lived alongside them in the community.

“In my little mind, a massacre is something unreal. It’s something that is hard to comprehend because we’re kind of a small people. We’re stuck on the same little piece of land … and we all live close together.”

Ivor said he is desperate to tell the world that help is needed on the reserve and in many First Nations communities. This was how he was making sense of his sister’s murder.

“We’re taking it as a teaching to give us the strength to voice what’s not being said,” he said.

Myles Sanderson’s troubled history

Darryl recalled Myles as a deeply troubled young man with a history of violence and substance abuse.

He also said that Damien did not seem to have the same entrenched issues as his brother, though he had lived a hard younger life.

“I had a couple of conversations with Damien. He was so respectful and he was trying, he was really trying.”

A summary of Myles’s younger life, detailed in the Parole Board of Canada decision, describes a life spent bouncing back and forth between the homes of his separated father and mother, physical abuse and domestic violence.

It also outlined a history of drug and alcohol use that began at age 12, when Myles began drinking alcohol and smoking marijuana. He began using cocaine at 14 and used crystal methamphetamine for a brief stint in his late 20s.

“You said that your regular use of cocaine, marijuana, and hard alcohol would make you ‘lose your mind’ and that you can be easily angered when drunk, but are a different person when sober,” the parole decision states.

The documents also say Myles had never been able to maintain long-term sobriety.

Saskatoon police confirmed shortly after the murders had been committed that they had been searching for Myles Sanderson since May, when he stopped meeting with his assigned caseworker and was classified as “unlawfully at large.”

Three months earlier, Myles had received a statutory release after serving four years and four months of a federal sentence for a series of offences including assault and robbery.

The statutory release was granted on the condition that he not contact his former spouse or his five children, avoid certain people, not consume, purchase or possess drugs and alcohol, and follow a treatment plan.

“It is the Board’s opinion that you will not present an undue risk to society if released on statutory release and that your release will contribute to the protection of society by facilitating your reintegration into society as a law–abiding citizen,” his parole document said.

His release came after an initial statutory release, in August 2021, which was cancelled after Myles resumed contact with his former partner, thus breaking one of his parole conditions.

Gloria would have wanted forgiveness

Darryl said the two men were the “products of residential schools” and “had a lot of anger.” He spoke clearly and concisely. Ivor stood by his side, nodding in approval.

“The battle we’re fighting here is not with each other. … The battle we’re fighting here is with alcoholism and drug use.”

The Sandersons, Darryl said, are “symptoms of residential school syndrome” where the “effects are rippling down to our children.”

While the community had begun to move on and heal, Darryl said he believes there could never truly be healing without addressing the substance abuse “epidemic.” He said they needed strong leadership from elders and mental health therapists to come in and help at-risk members.

Darryl said there was “no response” from the band’s leadership after he resigned and rose his issues with them on Monday. Calls to James Smith Cree Nation chief Wally Burns have gone unanswered.

Both brothers appealed directly to Ottawa for help.

“We can’t get help unless we ask for it,” Ivor said.

As RCMP trucks continued to trundle by in the background, throwing up plumes of dust in their wake, the men were adamant that they did not hold ill will toward the Sandersons. They said Gloria would not “hate them” and would want them to be forgiven.

Darryl concluded with one final message for the man who allegedly killed his sister.

“Myles, if you’re seeing this, give yourself up, Bud. There are a lot of people back here who are hurting. And we want to start healing.”

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.