The case of a Quebec man who received a conditional discharge after pleading guilty to sexual assault highlights the need to address “systemic” issues in how courts weigh an offender’s background, career prospects and potential in such decisions, experts say.

Quebec judge Matthieu Poliquin granted the discharge to Simon Houle last month, after Houle pleaded guilty to a 2019 sexual assault of a sleeping woman. In his decision, Poliquin said Houle’s assault happened “all in all quickly” and that a criminal conviction would hamper his prospects.

“A sentence other than a discharge would have a significant impact on his career as an engineer,” Poliquin wrote, adding: “It is in the general interest that the accused, an asset for society, can continue his professional career.”

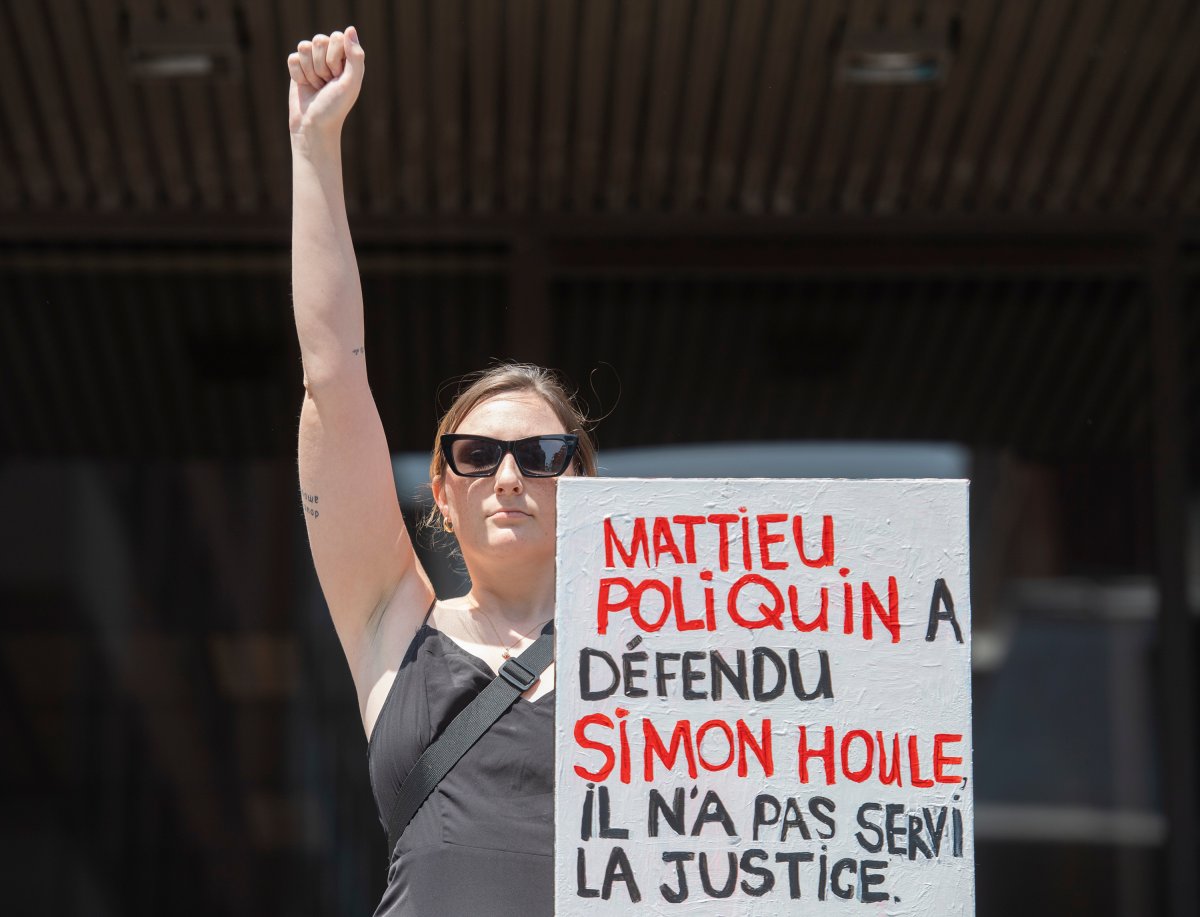

Since issuing that decision, Poliquin has been the subject of protests by hundreds of Quebecers condemning him and decrying what they have described as a lack of justice.

At least one woman held a sign suggesting Poliquin “defended” Houle rather than carrying out justice.

While Quebec prosecutors say they are appealing the conditional discharge, which was granted without Crown support, legal experts and gender equality workers say the Houle case and the judgement of Poliquin highlight important questions about the public interest and “systemic” injustice.

According to Section 730 of the Criminal Code, conditional discharges are supposed to be granted only when they are in the interest of the accused, and when they are “not contrary to the public interest.”

What that means, though, has not been clearly defined, said law professor Isabel Grant.

Get breaking National news

“It’s that ‘not contrary to the public interest’ that these cases turn on, and that’s what I wonder about in this case,” said Grant, who is a professor at the University of British Columbia’s Allard School of Law. “There aren’t a lot of guiding principles in these cases.”

Typically, she said, cases where courts feel a strong deterrent message is necessary are an example where giving a conditional discharge might be contrary to the public interest.

Grant added without all the details of the case that the judge had, it is difficult to say whether the decision fell short of meeting the requirement for conditional discharges not to be contrary to the public interest. But speaking generally, she said sexual assault cases must be taken seriously.

“The Me Too movement and those working in this area have tried to highlight the seriousness of sexual assault: the harm it does both to the complainant but to women who go through life with the constant threat of male violence,” Grant continued.

“Many women shape their behaviour around avoiding male violence – not walking alone at night for example – in ways most men do not experience.”

Broadly speaking, Grant added that Canadian judges have appeared to be taking sexual assault more seriously in recent years than they did a decade ago and said she hopes any women who want to come forward to report sexual assault understand that the conditional discharge is “an anomaly.”

“I also wonder, what if the accused weren’t a wealthy engineer – would he have gotten the same benefit of a conditional discharge?”

That question of whether it was appropriate for the judge to weigh the impact of a criminal conviction on Houle’s professional career and ability to travel is one also raised by a group of Quebec feminists.

In an interview with Global News, the president of the Fédération des femmes du Québec said the Houle case demonstrates the pervasiveness of rape culture in society, and emphasized the need for the justice system to play a stronger role in preventing sexual violence.

Mélanie Ederer described the conditional discharge as “a slap on the wrist and hope for the best” that shows why the fight for “systemic” social reform is far from over.

“What the judge said about his chances of being hired, of being able to travel –that’s not things that are said for other people in other crimes,” Ederer said.

“That’s why we have to think of it not just in the judicial system. We have to think of it systematically in the entire society. So how do we want to act in case of a crime? How do we want to act against a rape?

“Who is held accountable and who is protected?”

That conversation, Ederer said, remains lacking among Quebec’s political leaders.

But among women and allies on the ground, the case has fueled an already-burning flame.

A wave of outrage aimed at Poliquin has spurred countless posts online, with social media users saying they have filed official complaints about his conduct with the province’s judicial council.

Others are taking aim at Houle, calling for complaints to be filed with the Ordre des ingénieurs du Québec, the professional body that accredits engineers in the province.

Neither organization has confirmed receipt of complaints or indicated the amount received so far in response to questions from Global News.

Still, the rage persists.

“We’re mad. We’re truly mad,” Ederer said, urging anyone feeling angry or let down by the case to act.

“In every workplace, in every family, in politics, also the judicial system … say to women that we trust you and we will do what we can to protect you,” she continued.

“It has to be said. It has to be screamed.“

Comments