After a three-century wait, the last Salem “witch” can rest easy now that her name has officially been cleared.

Massachusetts lawmakers finally exonerated Elizabeth Johnson Jr. on Thursday, 329 years after she was convicted of witchcraft during the Salem witch trials. She was sentenced to death in 1693 but received a stay of execution along with a few other Massachusetts residents who had been charged. She was only 22 when she was sentenced.

In 1712, Johnson petitioned for exoneration of her charges but her request was never heard in court.

Her case was picked up in the modern day by a group of unlikely advocates: a Grade 8 civics class. Students from North Andover Middle School in Massachusetts championed the clearing of Johnson’s name and researched the necessary legislative steps to make it a reality.

“They spent most of the year working on getting this set for the legislature — actually writing a bill, writing letters to legislators, creating presentations, doing all the research, looking at the actual testimony of Elizabeth Johnson, learning more about the Salem Witch Trials,” Carrie LaPierre, the students’ teacher, told The Boston Globe. “It became quite extensive for these kids.”

Johnson’s exoneration was officially passed thanks to legislation introduced by state Sen. Diana DiZoglio, a Democrat from Methuen.

“We will never be able to change what happened to victims like Elizabeth but (we), at the very least, can set the record straight,” DiZoglio said.

Get daily National news

LaPierre echoed DiZoglio’s sentiments, saying, “Passing this legislation will be incredibly impactful on their understanding of how important it is to stand up for people who cannot advocate for themselves and how strong of a voice they actually have,” she said of her students.

According to Witches of Massachusetts Bay, a group devoted to the history and lore of the 17th-century witch hunts, Johnson is the last convicted witch to have their name cleared.

Very little is known about her. According to Emerson Baker, a history professor at Salem State, Johnson lived in Andover and never married or had children.

“We’re not even totally sure when she died,” Baker said in an interview with The Boston Globe.

Andover is a small town about 17 miles away from Salem. The town was swept up in its own witch-hunt frenzy after the fervour spread from Salem. Forty-five people were arrested for witchcraft in Andover, 28 of which were members of Johnson’s family, including her mother, Elizabeth Johnson Sr.

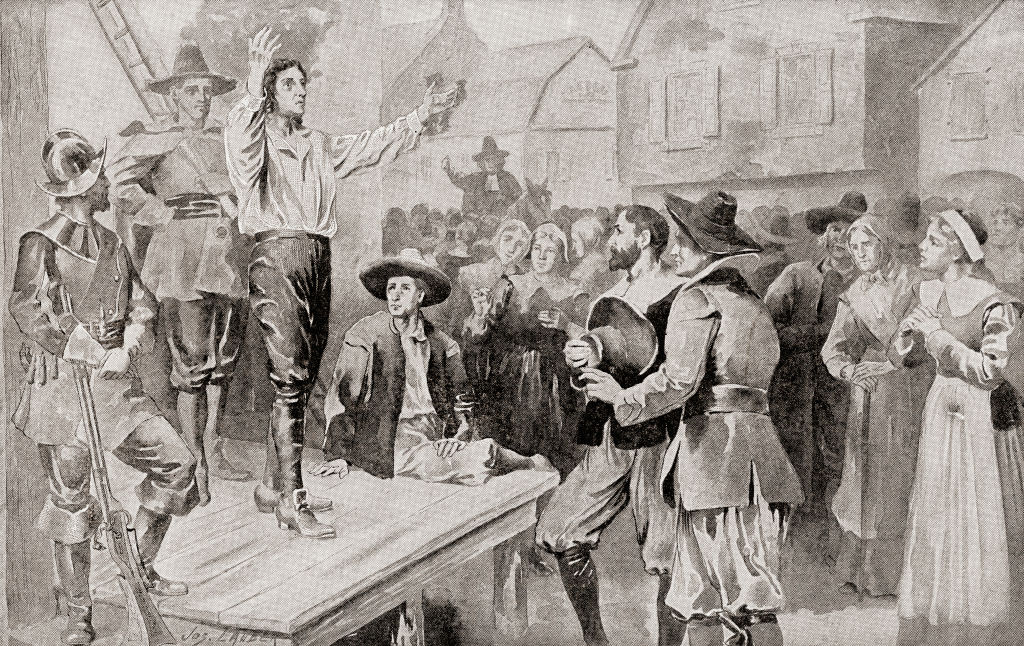

Twenty people were killed during witch trials in Massachusetts and hundreds more were accused. Nineteen were hanged and one man was crushed by rocks. Factors including superstition, misogyny, fear of disease, and petty squabbles all contributed to the Puritan frenzy that was driving the Salem witch trials.

In the centuries since then, dozens of accused “witches” have been cleared officially, including Johnson’s mother, but Johnson herself endured a long wait.

She was passed over in a legislative resolution that cleared one person in 1957 (and referred to “certain other persons”). In 2001, then-governor Jane Swift added five more names to the resolution.

“I’m a bit disappointed that we missed a person,” Swift said. “What has always resonated with me is that these are some of the earliest historical examples in the U.S. of women being vilified for acting outside of their accepted role.”

In a similar vein, DiZoglio said “Elizabeth’s story and struggle continue to greatly resonate today.”

“While we’ve come a long way since the horrors of the witch trials, women today still all too often find their rights challenged and concerns dismissed.”

— With files from the Associated Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.