Ontario is the worst offender among Canadian provinces when it comes to the lack of sufficient housing stock, according to a new analysis from Scotiabank Economics.

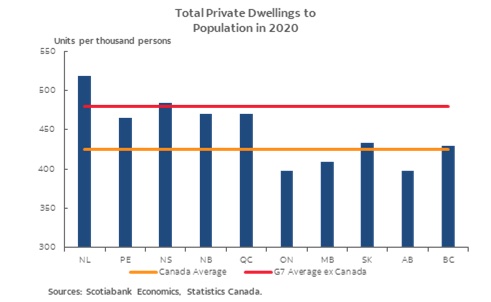

A report published Wednesday shows that Ontario, Alberta and Manitoba are the only provinces below the national average when it comes to per capita housing stock available. Scotiabank’s analysis relies on data from 2020, the last year with complete information on hand.

To make up the difference, Ontario would need to add 650,000 new dwellings, Alberta would need to build 138,000 units and Manitoba would have to construct 23,000 homes.

But as wide as some of these gaps are, striving towards the mean in Canada is not a high bar.

Canada already ranks lowest among all G7 nations for per capita housing stock, Scotiabank reported last year, needing more than 1.8 million homes to reach the average of its peers on the international stage.

Jean-Francois Perrault, senior vice-president and chief economist at Scotiabank as well as the report’s author, wrote that the delta between Canada and other G7 nations when it comes to housing points to the “collective failure in right-sizing the number of homes relative to our population.”

Need to reconcile immigration with intensification

It’s the growth of Canada’s population that’s become so difficult to manage, Perrault told Global News in an interview on Wednesday, with the pain points coming largely at the municipal level.

While the federal government has stated that it wants more immigration to bolster Canada’s economy, that sweeping directive comes up against obstacles at the city level, such as NIMBYism, zoning challenges and a lack of available labour or materials in the construction industry.

“There’s an economic imperative to have a lot more Canadians, which is fantastic,” he said.

Get weekly money news

“When it gets down to the nitty-gritty and the people are actually confronted with the day-to-day, what it means to have more Canadians from a real estate perspective, it’s a much, much more challenging situation.”

Ontario’s status as an attractive destination for immigration has made the shortage of available housing particularly stark, Perrault said. On the other end, Newfoundland and Labrador’s housing stock is the highest in Canada on a per capita basis, largely due to a decline in population through the mid-90s.

The ongoing shortage will continue to push up prices, Perrault says.

“If we don’t fix this, if we don’t right-size the number of homes in Canada or Ontario relative to population needs, things are never going to be more affordable.”

Provinces, feds looking for answers

There’s some optimism in the near term that Canada is taking the housing shortfall seriously, but it could be some time before the provinces are on track to fill the gap.

Conservative Party MP and shadow minister of finance Pierre Poilievre on Wednesday moved to study the drivers of inflation in Canada at the federal finance committee, with a particular focus on housing affordability. His motion passed unanimously with a report due by the end of May.

The federal government also has signalled plans for a housing summit to start examining how to fix the problem, though a date for that hasn’t been set.

Ontario also struck a task force on housing affordability late last year with the mandate to increase the supply of units for rental and ownership (Perrault notes in a disclosure the group is chaired by Scotiabank).

Housing starts are meanwhile picking up pace, Perrault says, enough to make a “small dent” in the housing stock gap. But it will take years of accelerated pressure to get the country’s housing market on track to meet the growing demand.

Until the dwellings are actually built, however, Perrault believes there’s little policymakers can do in the short term to make housing more affordable. Adjusting interest rates, for example, will do little to change the reality that home prices will rise as growing immigration levels continue to drive up demand for the stock that’s there, he says.

“In the short run, it’s very difficult to see how affordability is dramatically improved in the next year or two.”

Comments