Walking around the downtown core of any major Canadian city, it’s not unusual to see weed dispensaries nestled between restaurants and cafes. It would’ve been a pipe dream just a decade ago.

Since making marijuana legal, the Canadian government has continued to inch toward a softer drug policy.

The federal government introduced legislation Tuesday to repeal mandatory minimum penalties for drug offences, and Health Canada decided last year to allow some palliative patients to use psilocybin — the chemical compound in magic mushrooms — to relieve end-of-life suffering. Toronto and Vancouver have also called for the decriminalization of the possession of small amounts of drugs.

Taking all this together, experts say it’s clear we’re starting to “see a shift” in Canada’s stance on drugs.

“I see an acknowledgment that the war on drugs has been a failure,” said Dr. Akwasi Owusu-Bempah, an assistant professor in the department of sociology at the University of Toronto.

“I see a shift in the acknowledgment that many substances that are currently illegal — and people don’t have access to — can be used as medicines. And I see a shift just generally with respect to our openness and the use of drugs for pleasure.”

In a submission to Health Canada last month, British Columbia detailed its intention to decriminalize the personal possession of up to 4.5 grams of illicit drugs such as heroin, crack and powder cocaine, fentanyl, and methamphetamine. Vancouver has also made a similar submission of its own. And just one week ago, Toronto’s top doctor said she’d like to see the possession of small amounts of illegal drugs decriminalized in the city — and she’s got support from the local police chief.

The changes come as the country finds itself in the grips of an opioid crisis that worsened amid the pandemic. Between April 2020 to March 2021, a total of 6,946 apparent opioid overdoses were reported across the country — an 88-per cent jump from the same time period prior to the pandemic.

B.C. reported the highest-ever number of drug deaths in the first seven months of 2021: 1,204, surpassing last year’s record by 28 per cent. Drug toxicity is now the province’s leading cause of death for those aged 19-39, according to the B.C. Coroners Service.

In Ontario, opioid-related deaths rose by more than 75 per cent after COVID-19 hit in 2020, compared with the year before, a report by Ontario Drug Policy Research Network showed.

These figures point to one thing: “What we’re doing isn’t working,” according to Dr. Leslie Buckley, an addictions psychiatrist and the chief of addictions at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

“We’re trending up on all substances. Opioid deaths, crystal meth — we’re seeing so much of that — alcohol and cannabis are both on the way up.”

Canada's history with drug laws

Drugs have only been illegal in Canada for a little over 100 years, according to the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. Views began to shift in society in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the coalition’s website explains, mainly due to the “influence of Protestantism,” a growing unease in the medical community when it came to “unregulated medicine,” and a growing anti-opium sentiment.

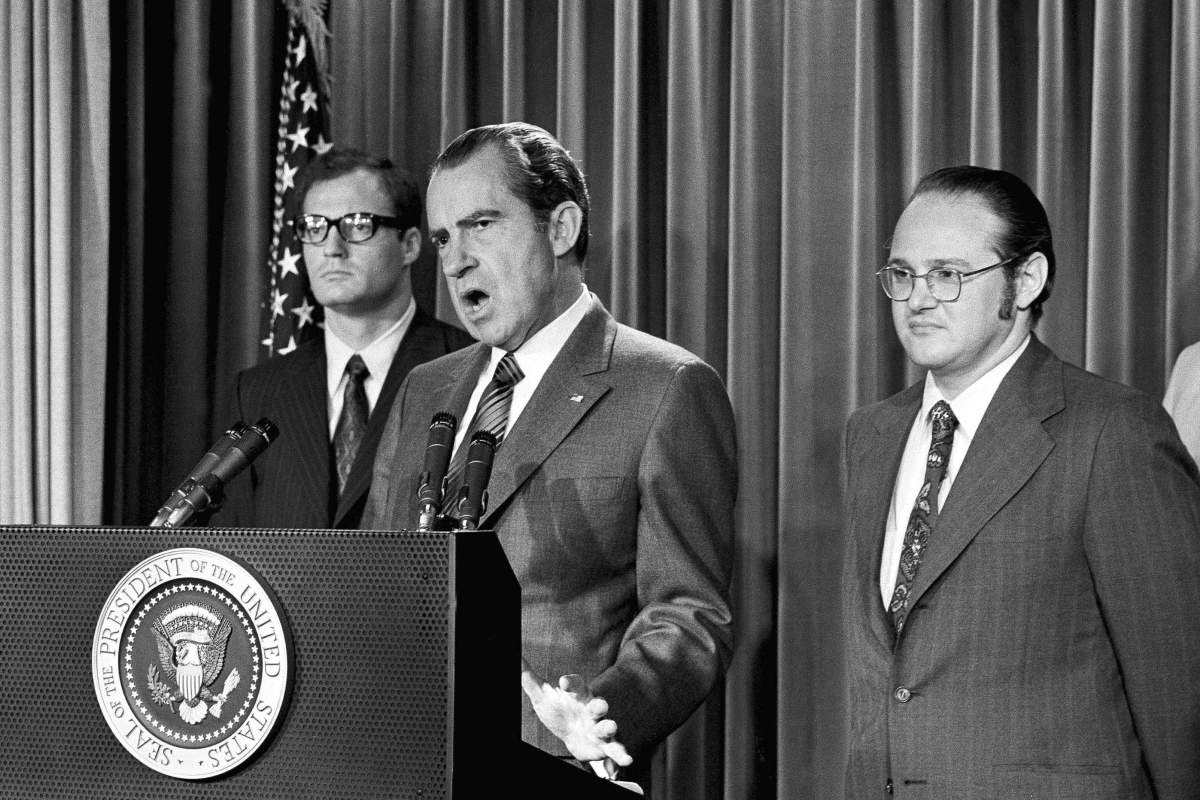

In 1971, then-U.S. president Richard Nixon kicked off the so-called war on drugs, declaring in a historic speech that the United States government planned to treat drug addiction as a “public enemy No. 1” that had to be defeated with a “new all out-offensive.”

Get breaking National news

Canada followed suit with a harsher approach to drugs in 1987, when then prime minster Brian Mulroney brought about Canada’s first five-year National Drug Strategy.

“The war on drugs has not only been ineffective but in many ways amplified some of the problems around substance use that it is presumably meant to address, by criminalizing users,” said Andrew Hathaway, a professor of sociology at the University of Guelph.

“If you recognize the drug problems are a matter of addiction, are a matter of dependence, things that are typically framed within a public health or a medical framework — it really makes no sense to keep up the war on drugs measures.”

Increasingly, policymakers seem to be in agreement with Hathaway.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has so far rejected wholesale decriminalization of simple drug possession and consumption. However, his government has taken some steps that treat drug use as a health issue rather than a criminal one.

In 2018, the Liberal government legalized marijuana. Also in 2018, the government made changes to the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, allowing health care providers to prescribe, sell or provide methadone without having to apply for an exemption with Health Canada.

The Liberal government is now trying to scrap mandatory minimums for drug offences, too, and is increasingly being lobbied by companies touting the medicinal benefits of magic mushrooms.

“I’m never averse to a positive suggestion or solution, and I’m always willing to assess that,” Justice Minister David Lametti added when pressed about the decriminalizing small-scale possession of drugs on Tuesday.

The new mandatory minimum bill would help “divert” people facing those kinds of charges away from the criminal justice system into “more appropriate forums to address those problems,” he said.

Conservative Leader Erin O’Toole also showed a slightly softer stance on drugs earlier this year, expressing his concerns about heavy-handed sentences for drug offences.

“It’s not appropriate to have very serious penalties for Canadians who have problems with drugs,” O’Toole said at a news conference in January, according to The Toronto Star.

Still, he does not agree with experts calling for the decriminalization of small-scale possession of drugs.

“We’ve seen horrible cases with opioids and other (drugs). Maybe it’s time for the government to put in place a plan for the well-being of Canadians, on the drugs and on mental health,” O’Toole said.

“It’s not the time right now to legalize all drugs.”

Trudeau’s government has not indicated any intention to legalize all drugs. The only proposals to date have dealt with the decriminalization of small-scale possession.

When asked for an updated statement on Tuesday, the Conservatives provided Global News with a statement from their justice critic, Rob Moore.

“Canada’s Conservatives believe those struggling with addiction should get the help they need to recover,” the statement read.

Overall, the policy changes and softening stances show that there’s a sea change happening with respect to Canada’s approach to drugs, according to Owusu-Bempah.

“I think we’re seeing some fairly large —I’d almost say momentous — shifts with respect to our view on what are currently a variety of illegal substances,” he said.

Addiction as a public health issue

The pervasiveness of drugs and addictions issue in our society is “not a problem that we can arrest our way out of,” Hathaway said.

“That’s been widely recognized for decades. It’s just it takes time for it to seep into the public consciousness.”

Humans have consumed drugs for thousands of years. The first evidence of opium use in Europe dates back to 5,700 BCE, according to The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness and Culture.

“People are using drugs now, and people will continue to use drugs,” Owusu-Bempah said.

There were over 70,000 drug offences committed in 2019, according to Statistics Canada’s data on police-reported crime. Just shy of 25 per cent of those arrests were related to cannabis, and 20 per cent were cocaine-related. There were also over 10,000 arrests made for the possession of methamphetamine.

Accordingly to Buckley, people begin using drugs for a variety of reasons. Issues like anxiety and trauma are “huge risk factors” when it comes to addiction — and it can impact anyone, from “any walk of life.”

That’s why something called “primary prevention,” which refers to an intervention that takes place before someone actually develops an addiction, is so important, Buckley said.

“We need some new, innovative ways to think upstream instead of just thinking about where we’re at right now, and really help young people make sure that they know the harms that they’re facing with substances today,” Buckley said.

“(We should) also think about making sure we have a robust mental health system so that young people can get their needs met in terms of anxiety and treatment for trauma, as those, as we know, often lead to substance use.”

Beyond addressing the root cause of addictions, shifting away from a punitive approach could also help usher in a more equitable society, according to Owusu-Bempah. That’s because the existing, more punitive approach toward addictions tends to disproportionately impact people of colour, he said.

“The racialized nature of policing and the fact that the police target Black and Indigenous people for stop and search activities means that those people are more likely to be caught in possession of drugs, even though rates of use are relatively similar,” Owusu-Bempah said.

According to the Ontario Human Rights Commission, Black people in Toronto represent 37.6 per cent of those involved in cannabis possession charges — despite representing just 8.8 per cent of the city’s population. White people are underrepresented, it also found.

When it comes to the possession of what the OHRC called “other” illegal drugs, Black people represent 28.5 per cent of those charged, despite making up a much smaller portion of the city’s population. They are three times more likely to be charged that a white person.

These arrests don’t just affect the individual, he said, but their families, too.

“Our drug laws have had intergenerational impacts in Black and Indigenous communities,” Owusu-Bempah explained.

Experts have advised a multitude of ways forward. Owusu-Bempah highlighted the importance of decriminalizing drugs and regulating their contents so that people consuming drugs are less likely to overdose. Buckley noted that we need more accessible treatment, more harm reduction, and more supervised consumption sites. Hathaway suggested funding social programs would help support those struggling with addictions — and the root causes for those addictions.

But all this, Hathaway said, would require governments “to move away from something that has been so firmly entrenched within our criminal justice system for such a long time.”

“The law is really just a codification of morality,” Hathaway said.

That means, though, that “to shift away from that version of the law means it inevitably will require a shift in ideology as well.”

— with files from The Canadian Press

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.