“Ralph Goodale will scrum with reporters at the media centre this afternoon.”

Scrum. I couldn’t believe my ears.

For 15 months, political reporters across Canada have had little to no access to what used to be a daily occurrence: a packed group shouting questions with microphones poised to hold politicians to account and hear their thoughts.

“Catching spit,” as my colleague David Akin often calls it, is not de rigueur in the time of COVID-19.

What we’ve mostly had access to are virtual press conferences, during which phone questions are limited, orderly and often controlled by political staffers.

We’ve heard a lot of “please press star one now” and “you’re on mute” — never a scrum where we can follow up freely and press for answers properly.

(Every political reporter can debate with you about the best strategy for the exact moment to press ‘star one’ in the lead up to a press conference so your question will be taken. The process can still be a mystery all these months later.)

We used to be able to wait for ministers and MPs in person at regular times throughout Parliament Hill before and after various meetings and question period. Now, not only are the majority of meetings virtual, if someone does appear in person, approaching can be a COVID-19 no-go, especially as a pack of reporters. And that means politicians can completely control whether they feel like speaking to media, and when — if at all.

Which brings me to what happened in the town of Falmouth, in Cornwall, England on Friday, June 11, where hundreds of media were camped out for three days to cover the G7 world leaders’ summit happening in Carbis Bay, about an hour away.

Parliamentary veteran Ralph Goodale, one of the most experienced, effective and verbose scrummers in recent history, now Canada’s High Commissioner in the United Kingdom, was being offered up to reporters to comment on the sidelines of the summit.

In the flesh.

No tenuous connection or dreaded “star one.”

Goodale spoke and took questions for well over 20 minutes, commenting on everything from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s conversation with the Queen, his bilateral meeting with U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson and the lack of one with American President Joe Biden and Canada’s vaccine contributions on the world stage.

The scrum expanded to include not just Canadian but international media who noticed it, pleased to see a human being standing in front of a microphone willing to take questions.

And there, outside in the British seaside air, standing masked and spaced out alongside reporter colleagues, well distanced from Goodale who had removed his mask to speak, I felt a wave of reporting adrenaline that has been lacking throughout 15 months of virtual mediocrity. I felt a new sense that normalcy and a return to holding people to account the way we used to do may just be possible.

Not to overstate it: Goodale didn’t make major news. He did provide clips for television and context on government positions, useful as we’d had zero access to other Canadian officials on camera since the trip began the day before (and never got access to any others, outside of the prime minister at two press conferences later on).

During the course of the G7, I conducted four other in-person interviews with experts, alongside colleagues. Five in-person interviews in three days felt like a pandemic record.

Overall, access to the main events at both the G7 and NATO summits was extremely limited. The only time I laid eyes on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in person were at the two media availabilities he held throughout the six-day trip.

Much of that was due to COVID-19 rules by summit organizers, but there was also a palpable lack of information from the Canadian side that no pandemic could excuse.

I have covered two previous G7 summits, and each had some opportunities to work and observe closer to the actual events. I’ve stood in the room for the opening of bilateral meetings including between Trudeau and former U.S. president Donald Trump and French President Emmanuel Macron.

I happened to pass former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in a hallway.

In these moments, body language and presence can share a lot more than you’re able to pick up virtually from a screen.

At the 2021 G7 summit, access to bilateral meetings was limited — not just for media, but official delegations were permitted fewer people in the room as well.

And then there was the infamous COVID-19 testing.

Get weekly health news

The U.K. government stipulated everyone needed rapid daily testing to be allowed into the various sites, as well as a PCR test upon arrival. That included Trudeau.

All the U.K. tests were self-administered: a new experience for the Canadian contingent, as regular rapid testing is not normalized in our country. In the U.K., people are encouraged to order free tests (they come in boxes of seven) and use them regularly.

At first glance, taking the test was more daunting than the prospect of reporting on and analyzing the G7 summit.

My hotel room turned into a mini science lab, with a vial, swab, liquid and test device all laid out as I tried to follow the instructions perfectly, terrified of an inconclusive result that would bar me from covering the event. Ok, four swabs of the left tonsil. Where exactly is my tonsil again?

A kind Canadian embassy staffer told me she’s taken at least 30 with no inconclusive results. That was reassuring.

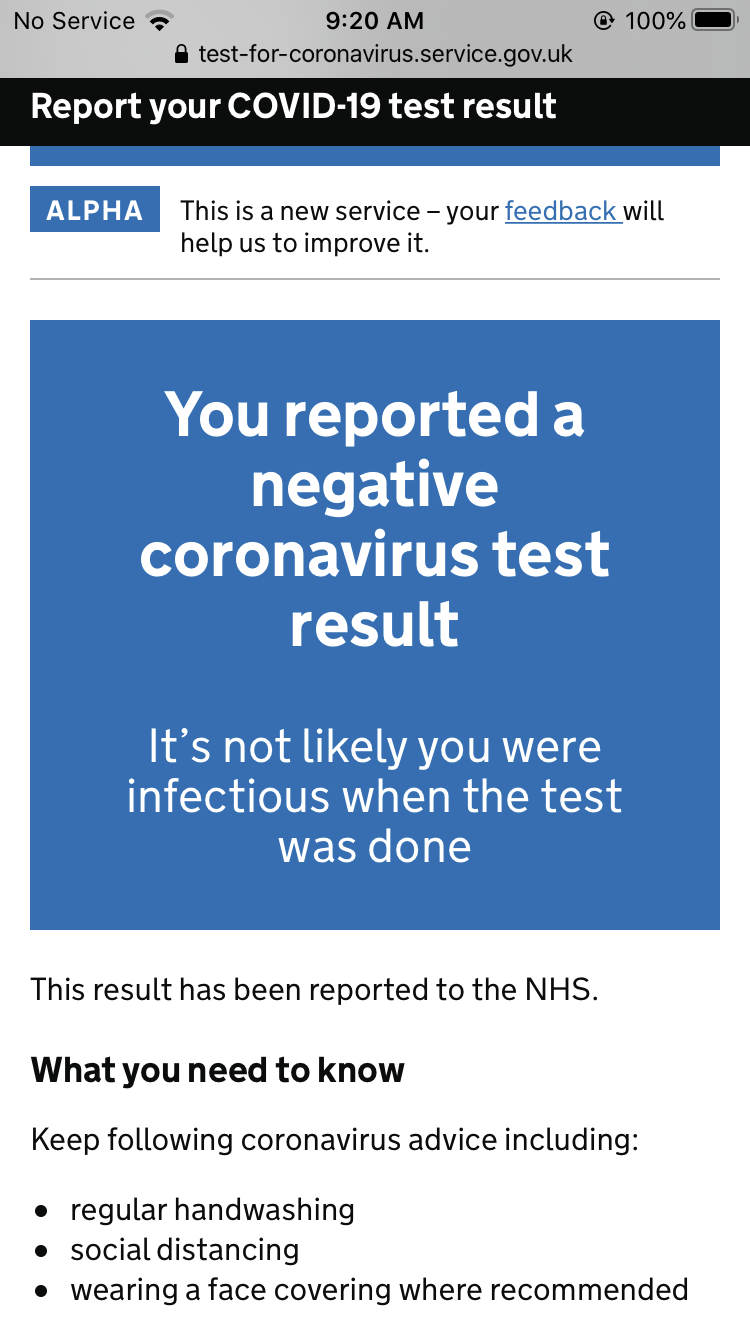

You couldn’t eat or drink for half an hour before the test, and had to wait 30 minutes after taking it before logging the result on a U.K. National Health Service website and answering a series of questions. That would produce an email and/or text message, which we’d show to security upon arrival at the media centre.

Over the course of the trip, the Canadian delegation took a total of nine PCR and rapid tests so far. One more will come on day eight in quarantine.

Interestingly to us journalist test-takers, the different self-administered tests, both rapid and PCR, seemed to come with different instructions, requiring different depths for that invasive swab (most were only about an inch deep, not that brain-scraping experience) and different numbers of “swabbings” from each tonsil and each nostril.

Canadian reporters eagerly shared gag reflex stories with each other — an experience that made an unusual work trip in pandemic life feel even stranger. I was made fun of for bringing along a tube of nasal lubricant, a suggestion from a physician friend that I maintain turned out to be quite helpful for a swab-irritated nose.

Not just testing, but all COVID-19 protocol seemed a little different wherever we went — but was top of mind everywhere.

In Cornwall, the media centre had plexiglass between each seat and signs to show whether they had been disinfected. You needed to wear a mask except when seated, eating or drinking.

In Brussels covering the NATO summit, there were no dividers between seats and no daily testing, but there was a temperature check. They also wanted masks on at all times, and insisted we wear a specific one: a European version closer to an N95.

Climate change was a focus at both the G7 and the NATO summit. It was incongruous that while there was an obvious effort to “go green” — I didn’t see a single plastic water bottle, all were made from glass or other recycled materials — disposable masks and rapid tests full of non-recyclable plastic mounded trash cans.

On masking: In the Twittersphere, much was made about photos of Trudeau masked or unmasked in various photos. This is the same prime minister who constantly reminds people to distance and mask up at home — never mind telling everyone now is not the time to travel — now spotted at receptions overseas standing very close to world leaders, unmasked.

It’s worth reminding people of two facts for context. First of all, Canada drags on the world stage in terms of full vaccination status.

While the prime minister constantly points to our star position in terms of people with a single dose, Canada is at the bottom of the list for double vaccinations among G7 nations, ahead of only Japan. So while Trudeau has a single dose of the vaccine, most everyone around him at those events and meetings would be fully protected.

And second, those daily tests.

Regular testing, while fairly ghastly and unpleasant, and without a perfect record of accuracy, did leave people with a feeling of safety and comfort.

I personally haven’t been in such close quarters with my own colleagues in 15 months, and I’m not talking anything dangerously packed, or fancy cocktail receptions with the Queen.

But regularly, there would be half a dozen of us on a minibus, or eating in a hotel restaurant. We stayed as distant as possible, and we wore masks more than were mandated, but regular testing certainly provided an extra feeling of security.

On trips with the prime minister, workdays are usually longer 12-15 hours. There is little to zero downtime to explore the places you’re visiting. It’s a work trip in every sense of the word. That was especially true on this trip, where we were asked not to go sightseeing or even leave our hotels by host countries.

But, like that scrum, there were fleeting moments that gave hope about a return to normalcy.

A patio lunch break with colleagues tasting local fare different from what swims in Canadian waters. A short walk to check out a protest and see Falmouth’s high street. I popped into one store to buy some local souvenirs for loved ones back home. Its employees were outside protesting, excitedly telling us, “This never happens in Cornwall!”

Since the start of the pandemic, gritting my teeth through countless virtual interviews and pressers and a loss of human connection, I have always held out hope access to politicians and an ability to hold them to account will return to pre-pandemic levels. I have some cynical thoughts about that.

With a potential fall election, many wonder if these summits serve as a template for covering a campaign. If they are, journalists will be pushing for more access to the people vying for votes.

Still, briefly visiting and working in two European countries and catching glimpses of a life, still altered, but closer to the one we used to know, left me buoyed about possibilities for our own future reality — on and off the job.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.