He knows his name, his identity and that he’s in hospital. While a Canadian man has been in vegetative state for 12 years following a car accident, neuroscientists at the University of Western Ontario say they’ve communicated with the man by concentrating on a string of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions.

He’s one of three brain injury victims the researchers have tried to reach out to. Their next steps are to consider how many more patients may be “trapped” in their bodies and if this technology could provide autonomy to these patients in making health decisions.

It’s uncharted territory in communicating with unresponsive patients – and with this breakthrough comes many questions, experts say.

“If in fact you can reach in and have some kind of communication then I would argue we have an ethical obligation to be really, honestly checking in with those patients and allowing those patients to weigh in on their own end-of-life decisions,” Dr. Kerry Bowman told Global News.

He’s a bioethicist and professor at the University of Toronto, specializing in end-of-life decision-making.

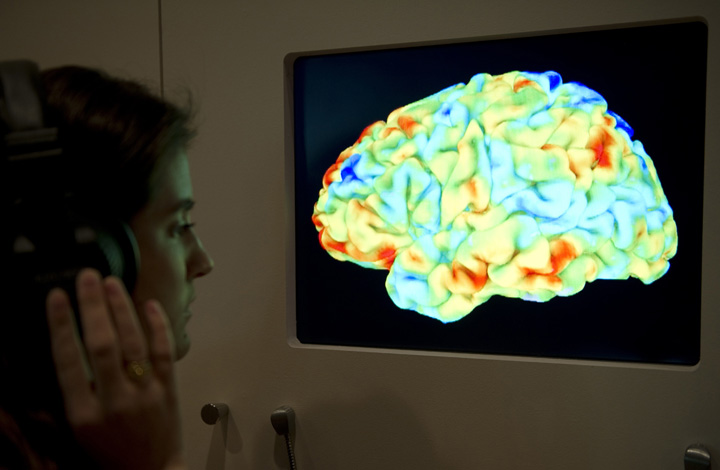

On Monday, Western scientists published their findings after working with three male patients – two from Ontario and one from Alberta – using a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner.

“From the moment they are diagnosed as being vegetative, they are thought to lack any form of cognition and they are lost to the world from that point on,” lead author Dr. Lorina Naci said.

- Trudeau tight-lipped on potential U.S. TikTok ban as key bill passes

- Canadian man dies during Texas Ironman event. Her widow wants answers as to why

- Hundreds mourn 16-year-old Halifax homicide victim: ‘The youth are feeling it’

- On the ‘frontline’: Toronto-area residents hiring security firms to fight auto theft

Read more: Scientists use Sesame Street to study brain development in children

In previous research, doctors have found that non-responsive patients can perform certain tasks, such as imagining playing tennis or navigating the rooms of their home. Since then, science has asked: what kind of mental lives are these patients able to sustain?

First, Naci and her colleague Dr. Adrian Owen, provided their subjects with music to determine if they can hear sounds compared to silence. Then patients were asked to follow commands to see if they could focus on the music and then relax and ignore the noise.

Turns out, the brain activity lessened when patients were asked to relax. “It shows that there is an internal, self-guided process from the patient to focus when asked,” Naci said.

Finally, the researchers tried to communicate with the patients. Simple questions – such as “Are you in a supermarket?” “Are you in a hospital?” “Is your name Mike?” – were asked as patients were told to focus on a response.

Naci said the subject from Alberta – he went into cardiac arrest following an altercation in 1997 – became “very unsettled.”

But the 38-year-old Ontario man who had been in a vegetative state since 1999 showed striking awareness of his situation.

“The patient was highly cognitively preserved and alert as you and I would be,” Naci said.

“This means they can hear their loved ones and doctors, they can understand but they just cannot respond. They are trapped in their bodies,” Naci said.

Misdiagnosing patients who aren’t in a vegetative state happens more frequently than Canadians realize, Naci said. Some studies have suggested that up to 20 per cent of patients can communicate via some sort of command following.

“Up to 40 per cent of patients in a vegetative state are misdiagnosed. So there is room for improvement,” she said.

Read more: Doctors requesting ‘unnecessary lower back MRIs: Canadian report

Naci wants to try the process with more patients to get a pulse of how many could be alert. She also wants to check on patients’ mental health, perhaps ask if they are depressed, for example.

“If they are communicating with us, we can take those answers seriously and act on them. We may then be able to involve them in health care decisions and give them some sense of autonomy they have lost,” she explained.

These are just baby steps but as the technology advances, other hot-button issues surface.

“We need to follow this research very carefully because I think the implications for end-of-life decisions are massive with this research,” Bowman said.

He suggests that right now, the resources may be limited and the accuracy may be questioned but if science turns this technology into common practice, every patient should be tested. And if patients show they’re present and cognitive, they should have the right to make decisions on their behalf.

“In Canadian law, to be capable they don’t need to tell you what month it is or who the prime minister is. That’s not the legal threshold. They just need to understand and appreciate the situation theyre’ in,” he explained.

“There is nothing in the law that says they have to be able to sit up and have a conversation with you.”

Read more: 6 Canadian game-changing ideas for global health care

Ryan D’Arcy, a neuroscientist at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, made his own device – called the Halifax Consciousness Scanner – that helps detect brain activity in patients.

In this case, it’s a rapid diagnostic tool that measures brain processing, treating the brain like a vital sign. It’s akin to measuring heart rate or blood pressure, he says.

The difference is, his technology doesn’t interact with vegetative patients.

“You certainly would want the science and technical capability well-demonstrated, proven, examined and accepted by the scientific community,” he told Global News.

Naci said she is glad she was able to make contact with the patient – his family had insisted they knew he was still conscious.

“I feel this family always had this sense that the patient may be there even though it wasn’t obvious to the medical staff. I feel happy the family was vindicated,” she said.

Read more: Mandela’s long hospitalization sparks end-of-life discussions in South Africa

Bowman said he’s worked with many families who are certain there’s life behind their loved one’s lifeless body.

“People in vegetative state do move. Their eyelids flicker and they have involuntary movements and sometimes that’s interpreted as responses,” Bowman said.

“Often when families say they think they’re responses, they’re not taken seriously. Sometimes, they are wrong but sometimes these families are right all along.”

carmen.chai@globalnews.ca

Follow @Carmen_Chai

Comments