B.C. resident Sukhdeep Singh is concerned about a potential crackdown turning deadly in India as pressure mounts over the historic farmers’ protest.

“Things are actually moving in the same direction that was done back in 1984,” Singh said.

He’s not alone. The sequence of events that led up to the horrific sights witnessed across India in 1984, by a now-haunted generation, is being recalled by people across the province and around the world.

Those concerned about mass violence today say India’s repeated communication blackouts around the massive protest site, attacks on dissenting voices and arrests of activists and journalists in recent weeks are terrifyingly similar.

The slaughter of Sikhs in New Delhi 36 years ago is etched in their collective memories.

Now, familiar fears are being felt amid increasing tensions around the agitation against India’s new agriculture laws and how some of those farmers are being framed as extremists by government supporters.

“We have plenty of evidence of how they systematically built that hate and started portraying one part of the community as an anti-national (in 1984),” Singh said.

“The same thing is happening now. When you are asking for your constitutional right and you are being portrayed as an anti-national.”

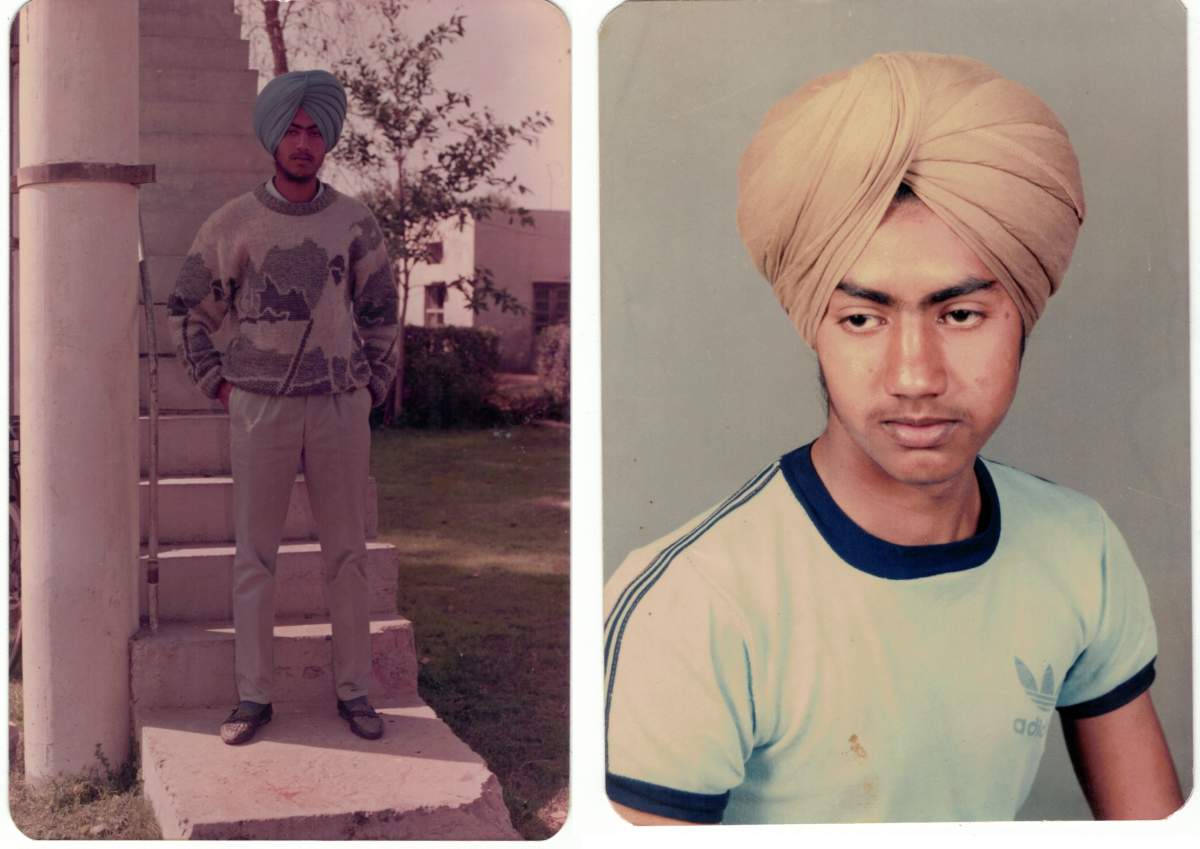

Singh, an independent documentary filmmaker, has focused his work on the events in 1984 and how they unfolded. He was 15 years old when the massacre happened.

He recalls being in Grade 9 at the time, a student with dreams watching his world crumble around him.

“I would say that was the worst time of my life,” he said, adding he feels lucky not to have lost any immediate family members. But living through a genocide of his people, happening within his own community, has taken its toll.

Get daily National news

“The whole focus is survival and that affected everyone, and me as well, that affects your development,” he said.

“That’s why people started looking at how to escape the situation, that’s why there’s the biggest migration, people are not just here for a better life.”

- ‘Buy Canadian’ policy likely to cost taxpayers $12 billion yearly: study

- ‘A foreign policy based on short memory’: Carney continues push to diversify from the U.S.

- Washington must avoid new tariffs with Ottawa: Canadian and U.S. mayors

- LeBlanc heading to D.C. after Carney says CUSMA ‘broken in the short term’

Sikhs make up around two per cent of India’s population, but have been heavily featured as faces of the movement, and often portrayed as as anti-national extremists or even terrorists.

While the Indian government has a documented history of human rights abuses, some say the current crackdown on the press, activists and farmers, is different this time around

“The diaspora tried to define what Khalistan is, they tried to define what it means to be a Khalistani in many different ways than perhaps India was defining it,” Satwinder Bains, director of the South Asian Studies Institute at the University of the Fraser Valley, told Global News.

“There’s a large number of people who are starting to question the idea of terrorism attached to the Khalistani movement and trying to address the idea of an emotional attachment of the land. So I see a difference to what happened in 1984, but certainly it has raised this kind of ire in people’s minds,” she added.

The trauma from 1984 and the years that followed, runs deep for the community, Bains said.

“Part of the reason is because it hasn’t been resolved between government and people,” she added.

Today, as tens of thousands of farmers remain camped out on the outskirts of India’s capital city, fighting not only the new laws, but for their right to peacefully demonstrate, the kind of polarization that led to one of the country’s darkest chapters is being sparked.

In June of 1984, after violence and failed negotiations between the government and protesters, the Indian army attacked Sikhism’s holiest shrine, the Golden Temple.

Code-named Operation Blue Star, the government’s aim was to flush out separatists from the Golden Temple.

The Sikh community around the world reacted strongly with anger and sorrow at the attack of their most sacred site.

Four months later, in retaliation to Operation Blue Star, two of Prime Minister Indira Ghandi’s Sikh bodyguards assassinated her.

What followed in November of 1984 was the mass slaughter of Sikhs in Dehli.

Growing criticism of Indian prime minister

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government’s current clampdown on farmers, journalists and activists even has the Khalsa Diwan Society in Vancouver, which went against protesters and hosted him in 2015, rethinking that move.

“What’s happening today, if I had of known it, we would live in better, different decision, but not at that time, nobody suspected that,” Khalsa Diwan Society president Malkiat Dhami told Global News.

“The farmers are fighting for their rights, fighting for the protection of their property in the future, they’re fighting for their livelihood,” he added.

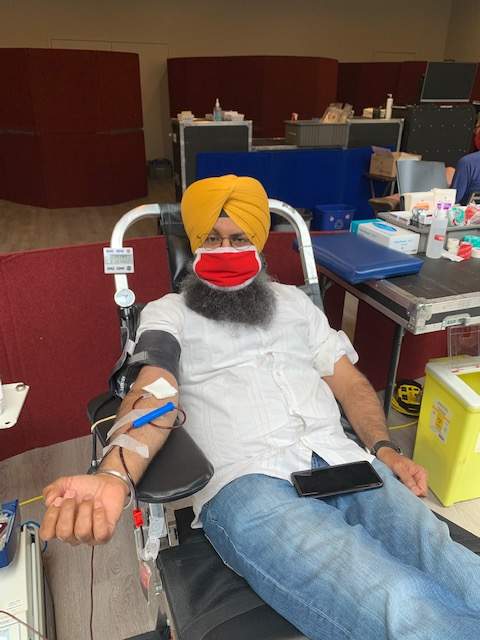

In honour of the victims of 1984, Sikh Canadians hold one of the country’s largest blood drives every year.

“Bringing a positive mindset, love, compassion, care, equality, that’s the only way to go,” Singh said, adding “any tragic event is not just a sequence of events, there’s a mindset behind it, so if you really want to avoid the future genocide, avoid any tragic happening, you need to tackle the mindset.”

Singh, who’s been a volunteer since the blood drive’s inception in 1999, hopes living and acting in love and compassion will reflect in society on a broader level and believes this is the best way to prevent the past, from predicting the future.

With files from Neetu Garcha

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.