As major oil and gas producers and exporters, Norway and Canada share a particular responsibility for confronting the planet’s existential climate threat. However, their different political, economic and cultural features have resulted in major differences in their climate policy track records.

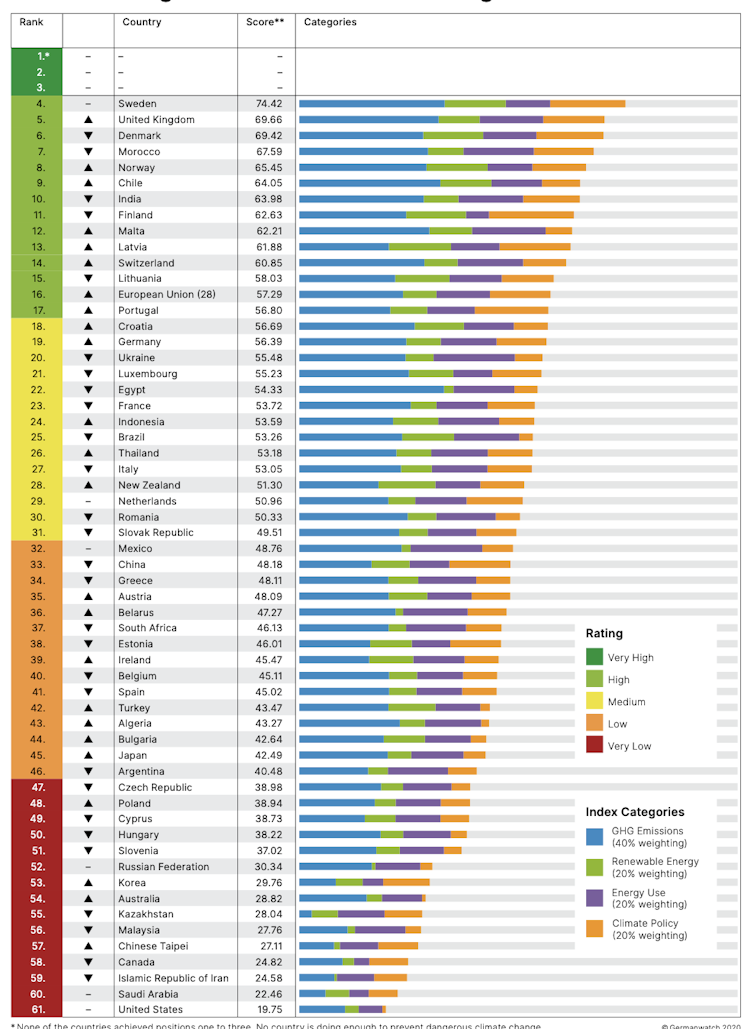

Overall, Norway is a leader in climate change performance and Canada is a laggard. The 2021 Climate Change Performance Index ranks 61 countries on their progress in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, energy consumption, renewable energies and climate policy. Norway ranked eighth overall, while Canada was near the bottom in 58th place.

Both countries face epic challenges in weaning themselves from petroleum dependence — and putting an end to exporting carbon emissions. Canada is a long way from winding down the oil and gas industry and implementing a green and inclusive recovery.

One of the advantages Norway holds is the high degree of equality and inclusivity in the policy process, which translates into a healthier democracy than Canada’s. This is something Canada can learn from and improve upon.

Canada produces 4.7 million barrels of oil per day — 80 per cent of it from Alberta — and exports 79 per cent to the United States. The carbon emissions from the consumption of those fossil fuel exports are almost four times greater than the emissions produced in their extraction and processing. These emissions aren’t attributed to Canada, even though it’s responsible for making them available.

Norway produces 1.7 million barrels of oil daily and, since the country runs mainly on hydroelectricity, exports almost all of it, largely to Western Europe. Norway exports 10 times more emissions than it produces domestically.

Norway’s exit ramp from oil dependence is bumpy. Despite some contradictory climate actions, Norway’s progress exceeds that of virtually all petro-states, with Canada trailing behind.

Norway has committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 50-55 per cent compared to 1990s levels by 2030, largely through domestic actions. Norway is the world leader in electric vehicle sales; by 2025, all new cars sold will be zero-emission vehicles. Only 3.3 per cent of passenger vehicles sold in Canada during the first half of 2020 were electric.

Norway participates in the European Union’s Emissions Trading System, the world’s largest carbon market, and has spent billions on international offsets in developing countries through its REDD+ program to maintain and expand their forests as carbon sinks.

Get daily National news

Canada recently introduced legislation to meet or exceed a 30 per cent reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 compared to 2005, in part by boosting its carbon tax, but continues to heavily subsidize fossil fuel production. Since early 2020, Canada has allocated US$14.6 billion to support fossil fuel energy and an equivalent amount on clean energy.

Norway also spends a lot on its fossil fuel industry — at least US$11.76 billion since 2020. And with an economy that runs largely on renewable energy, it allocated only US$382 million to renewables.

Neither Canada nor Norway has achieved absolute emissions reductions. Industry in both countries downplays this reality, choosing to focus instead on their progress in reducing carbon intensity — emissions per barrel of oil.

Neither country has committed to a production endgame either. Denmark is the first major oil-producing country to commit to terminating state-approved oil exploration in the North Sea and ending all oil extraction by 2050.

Canadian carbon emissions increased 20.9 per cent between 1990 and 2018, mostly driven in turn by a five-fold expansion of oilsands emissions. Canada’s energy regulator predicts oil production overall will grow 41 per cent from 2018 to 2040.

Norway’s emissions increased three per cent between 1990 and 2018, and it continues to sell oil leases for offshore drilling including in the Barents Sea and the Norwegian Sea. Canada has imposed a moratorium on Arctic offshore drilling.

Canada and Norway’s paths to carbon zero have, for the most part, diverged, with Canada falling behind badly.

- In Norway, the state-controlled company, Equinor, and the government jointly determine climate policy. In Canada, petroleum corporations have more leverage on climate policy because they control their production and investment decisions at home and abroad, and are accountable only to their shareholders.

- Norway is a unitary state giving the government uncontested jurisdictional authority over climate policy. As a federal state with divided jurisdictions, the Canadian federal government is in a much weaker policy-making position.

- There is a high degree of political stability on climate action in Norway. Even the right-wing Progress Party acknowledges the climate threat and supports the government’s climate plan. In Canada, wide swings on climate policy over the past 40 years have thwarted sustained advances. While a majority of Canadians now support decisive action on climate change, there are splits along party lines and geography, with most Conservative provincial governments opposing a carbon tax.

- In Canada, especially under Conservative governments, there has been very little consultation with labour unions and NGOs on climate policy, whereas in Norway these consultations are viewed as essential in shaping policy, regardless of the government in power. Additionally, Norway’s lower levels of economic inequality and stronger social safety net reinforce its robust democracy.

- Alberta squandered its oil wealth on low provincial taxes and corporate giveaways. The province created the Alberta Heritage Fund in the 1970s, but it currently contains only US$12 billion. Norway on the other hand, created a sovereign wealth fund in 1996 to retain the bulk of economic rent from the oil and gas extraction. The fund now holds US$1.3 trillion in global investments, which facilitates its climate transition. The fund’s return on these investments in 2019 was US$180 billion, and in 2020 it sold the last of its money-losing investments in foreign fossil fuel companies. The Norwegian government is still highly dependent on the petroleum sector, but fiscal rules allow it to draw up to four per cent annually from the sovereign wealth fund returns if net petroleum transfers fall short of spending requirements.

There is plenty of room for Canada to increase taxes on the wealthy and corporations. It can also strengthen its public investment banks and expand the Bank of Canada’s “quantitative easing” efforts, namely holding government-issued debt to provide the necessary resources for an equitable and sustainable transition.

Governing the decentralized Canadian federation is complex. This puts more weight on political leadership in all parties, in all regions, to acknowledge the truth about the climate crisis and build the necessary consensus to meet the challenge.

Political leadership is the art of persuasion: learning from the past, building coalitions, taking bold action. As a major carbon emitter, Canada must fulfil its global responsibility in helping to stop this runaway train.

Denial, delay and division are no longer an option. Leadership that fails avoid a cataclysmic future will be judged harshly by our descendents.Bruce Campbell, adjunct professor, Faculty of Environmental Studies, York University, Canada.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.