Ottawa’s health and social services providers are bringing attention to the disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 on the city’s Black and racialized communities with a new data release showing just how jarring the discrepancies in coronavirus infections are between white and non-white residents.

The latest release from Ottawa Public Health analyzes COVID-19 data collected across the city from February to August, stripping away infections that took place in long-term care homes, congregate living settings and people who have died.

There were 1,444 people who met OPH’s criteria and responded to the sociodemographic survey, roughly half of the total number of residents who had tested positive by that time.

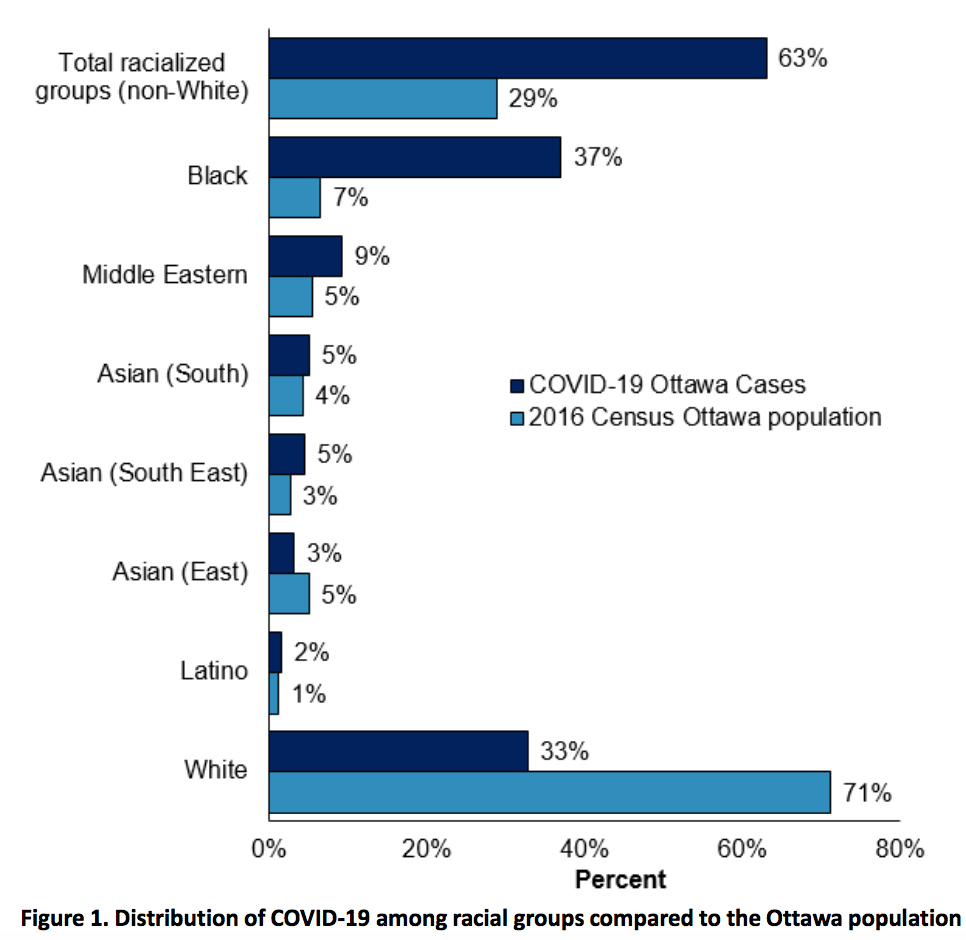

The report shows that Black people make up 37 per cent of all coronavirus cases in Ottawa since the start of the pandemic, despite making up just seven per cent of the overall population.

In total, racialized residents account for 63 per cent of all coronavirus infections compared to making up 29 per cent of the city’s population.

Across most of these groups, women are also more likely to have been infected with the coronavirus, according to the data.

Conversely, white residents represent roughly a third of all COVID-19 cases despite representing 71 per cent of Ottawa’s population.

The statistics on racial identity and COVID-19 in Ottawa are stark, said Hindia Mohamoud, director of the Ottawa Local Immigrant Partnership, in a press conference on Tuesday.

“It is overwhelming. It is concerning. And it is urgent,” she said of Black people’s overrepresentation in the data.

Get weekly health news

Racialized communities are harder hit by COVID-19 for a number of reasons related to the social determinants of health, which include housing, employment and access to food, transportation and health-care resources. Systemic racism in health care can also affect an individual’s access to care, according to experts.

Mohamoud said Black residents are facing higher rates of the virus because, in many cases, they were the ones who stepped up to keep the city running during the early lockdowns by working in the front-line service or health-care sectors.

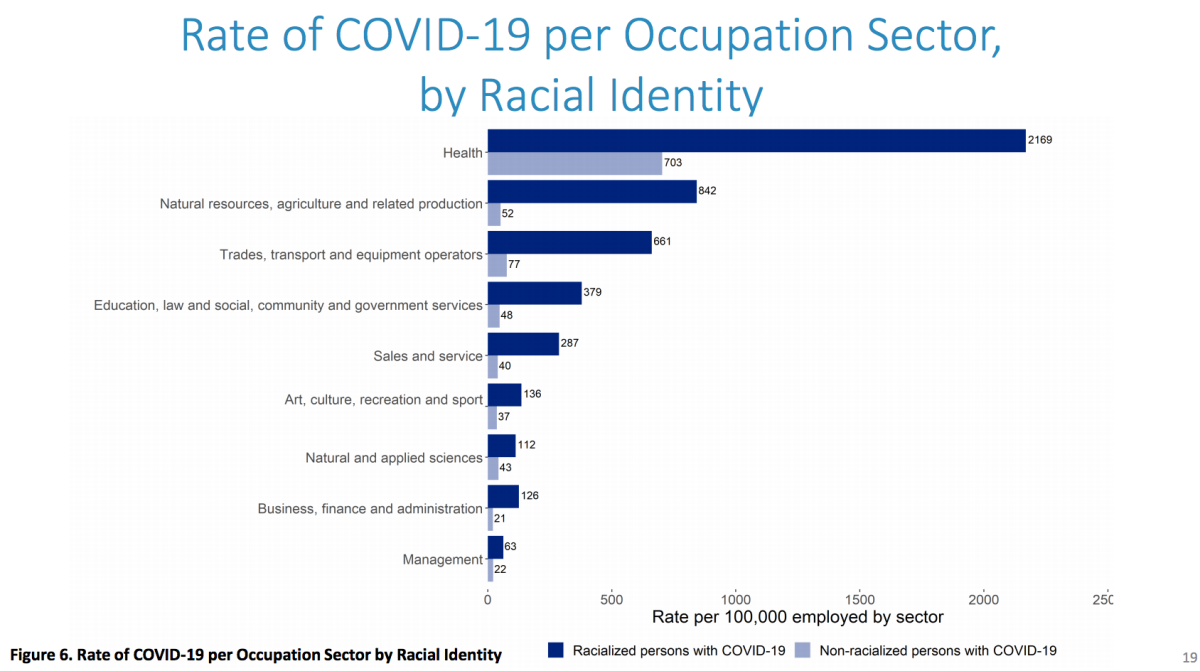

For example, racialized workers in health care report rates of coronavirus infection three times that of their white counterparts, according to the data.

“They did the hard jobs, the essential jobs. And that exposes them to a high risk of infection,” she said.

The OPH report did not include data on the relationship between income and COVID-19 infections, though Ottawa’s medical officer of health Dr. Vera Etches said there are “connections” between people’s employment and their ability to stay home from work or access benefits when they’re sick.

Naini Cloutier, executive director of the Somerset West Community Health Centre, also noted that recent immigrants might not be fully aware of their rights as workers and could worry about confronting an employer about working conditions if their job is perceived to be at risk.

Ottawa is among the cities in Canada with the highest household median income, but Etches said that “those advantages are not spread out universally.”

The Ottawa Health Team (OHT), which includes OPH, OLIP and community health centres, is working on “targeted” strategies to address neighbourhoods in the city facing higher rates of infection.

It’s not enough to just set up a pop-up testing site in a neighbourhood and ask people to show up and get tested, Cloutier said. The confusion and stigma surrounding COVID-19 could prevent an individual from presenting for an assessment, for example.

Cloutier said strategies such as bringing registered nurses who speak a community’s first language to talk residents through the process can be productive in promoting understanding.

The OHT is also working on promotional campaigns through bus stops and holding forums within marginalized communities to hear their direct concerns about the pandemic.

Andrea Gardner, OLIP co-chair and associate executive director of Jewish Family Services, said Tuesday that while the disparities in the pandemic require immediate funding and support to build resilience in marginalized communities, the issues that led to these impacts existed before COVID-19 and will exist well after without long-term action.

Disadvantages such as unstable employment, reliance on public transit, overcrowding in homes and lack of reliable access to food are cracks in Ottawa’s social system that only became more apparent when the pandemic hit, she said.

“These work and life conditions have become a matter of life and death,” Gardner said.

Etches noted that the OPH report does not include information on Indigenous populations, though the local public health unit is working with First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities on strategies to address the impacts of the pandemic on their lives as well.

Etches also said that one thing Ottawa residents of all ethnicities can do to keep COVID-19 out of at-risk communities is to continue taking actions to limit the spread of the virus in the first place.

Ottawa continues to report lower levels of COVID-19 compared with other areas of the province, with 19 new coronavirus cases on Tuesday.

OPH confirmed to Global News that a reporting issue that saw Ontario overreport cases on Monday and underreport on Tuesday does not affect the local public health unit’s daily reports.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.