A new report has found that immigrants, refugees and other newcomers made up 43.5 per cent of all COVID-19 cases in Ontario as of mid-June, despite those groups representing just over 25 per cent of the province’s population.

The report also found that testing rates were lower for immigrants and refugees when compared to Canadian-born and long-term residents, with the exception of Ontario immigrants who are classified as “economic caregivers.”

“The first thing that stood out for me, and which I think is somewhat actionable, is that clearly there are groups of immigrants who overall the testing rates were a little bit lower than in comparison to Canadian-born,” said Dr. Astrid Guttmann, the lead author of the report and chief science officer at Ontario research organization ICES.

“There were certainly certain groups of immigrants where the percentage of tests that come back positive was quite high, and that’s a really key marker from a public health perspective of whether or not we’re getting out and testing communities.”

Guttmann said the findings of the report reflect the barriers of accessing coronavirus testing.

“That’s really an important message that we need to be carefully monitoring,” she said. “Public health units get the data on who’s positive, but they actually don’t always know within communities who’s being tested and what percentage that is.”

According to the report, immigrants and refugees from world regions where a majority are racialized in Canada — including Central, Western and East Africa, South America and the Caribbean — experienced the highest rates of COVID-19.

“Causes of these inequities are complex and often rooted in social and structural inequities, including systemic racism,” the report reads.

“For COVID-19, occupational risk is critical considering the over-representation of racialized and immigrant populations, especially women, in essential work.”

Many of those essential worker jobs are public-facing and low-paying, the report says, and include health and social care workers, retail grocery store employees, public transit drivers, among others.

The report says immigrant and refugee communities are also over-represented in occupations that take place in settings like factories or meat-packing plants, where physical distancing is difficult and personal protective equipment was not universally available initially.

Get weekly health news

“It’s really about where you work and where you live,” Guttmann said. “Those are the two big risk factors.”

Other findings of the newly released report indicate that while testing rates were higher among those living in low-income neighbourhoods in Ontario, positive coronavirus test results were strongly correlated with living in low-income neighbourhoods for immigrants, refugees and newcomers — not for Canadian-born and long-term residents.

“It’s one of the findings that puzzled us the most,” Guttmann said. “Why would it be that living in a low-income neighbourhood would be so much more of a risk factor for immigrants and refugees than Canadian-born? We don’t know. We’re exploring it a little bit more.”

The report also found neighbourhoods with high household densities were associated with higher positive COVID-19 cases in Ontario in general but even more so for immigrants, refugees and other newcomers.

“Crowded living arrangements are more common in some immigrant populations with multigenerational households, and more generally for those of low income,” the report says.

The report indicated that socio-economic factors were also related to people testing positive for COVID-19: adult immigrants and refugees with fewer years of formal education who spoke little English or French at the time of immigration were associated with lower COVID-19 testing rates but a higher per cent of positive coronavirus cases.

“A number of public health initiatives may help to mitigate the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 infections as Ontario prepares for the possibility of a second wave of infections in the fall,” the report reads.

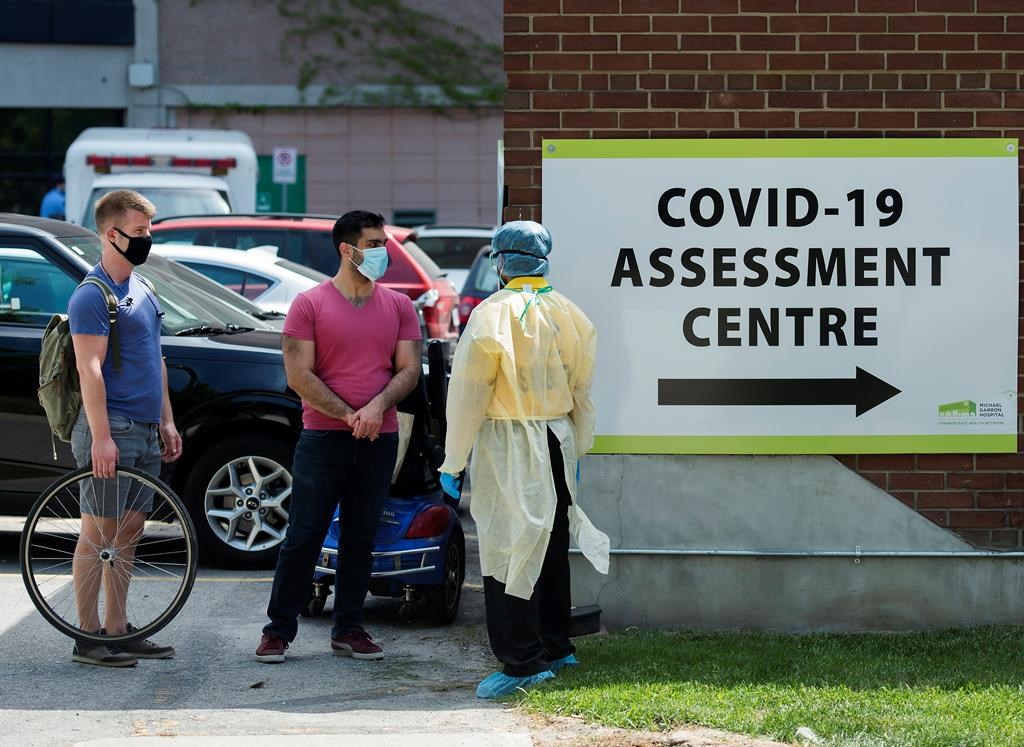

“This includes initiatives such as more accessible testing options, including mobile testing to help identify and address barriers to testing.”

The report says it’s also important for Ontario’s public health units with large immigrant and refugee populations to work with local groups that represent those communities.

“The piece around housing I think is really important,” Guttmann said. “Some of the public health units — Toronto, for example — has started to fund housing people to quarantine if they live in circumstances where households are very crowded and there’s no way for them to safely quarantine. That’s very important.”

Guttmann said it’s also vital that protections are in place for people who are in occupations that put them at risk.

“In the long-term, it is critical that efforts be made to address the social and structural issues experienced by temporary and permanent immigrants and other racialized groups,” the report says.

The ICES report analyzed coronavirus tests and results from Jan. 15 until June 13 for all the province’s residents who are eligible for OHIP — apart from those living in long-term care homes.

The characteristics that were measured include age group, sex, immigration status, country or world region of birth, Canadian language fluency, employment as a health care worker, neighbourhood income, number of people per dwelling and public health unit of residence.

The report notes some limitations, including the challenges in interpreting positive COVID-19 rates in the context of Ontario’s testing strategy, which has developed over time.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.