A pair of explosions erupted in Beirut, Lebanon, on Tuesday night, creating a wave of destruction that has so far claimed more than 150 lives and injured thousands more.

The seismic impact of the blast was recorded hundreds of kilometres away. It levelled dozens of buildings, stretching from Beirut’s industrial waterfront to residential neighbourhoods and popular tourist districts.

The city’s governor estimated up to 300,000 people had lost their homes. UNICEF estimates some 80,000 children have been displaced.

The exact cause of the explosions is still undetermined, but officials believe the larger blast was caused by the detonation of more than 2,700 tons of ammonium nitrate, a highly explosive material that had been stored at the port for the last six years.

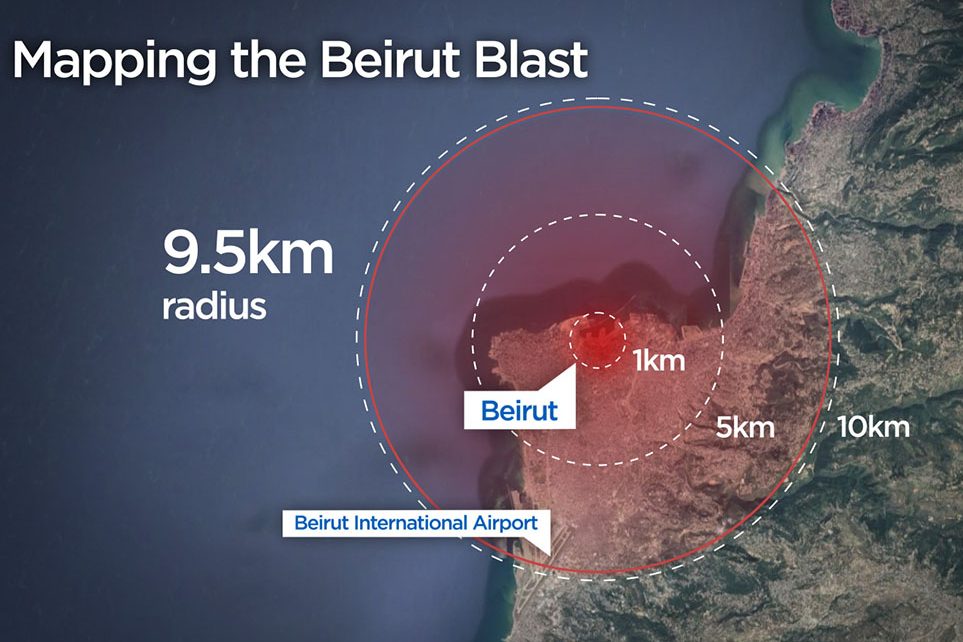

That second blast caused the most widespread destruction. It could be heard more than 100 miles away in Cyprus and shattered windows at Beirut’s airport nearly 10 kilometres away.

Areas nearest to the blast site understandably took the brunt of the shock wave. Other warehouses on the port were destroyed, a ship was capsized on the water, and patients were evacuated from the nearby Karantina Hospital.

Video of the second blast shows the speed at which the explosion tore across the city, leaving rubble in its wake.

Should an explosion like the one in Beirut ever occur in Canadian cities, the damage could be just as great.

Mapping the blast in Canada

Get daily National news

The following maps show three rings representing different levels of damage: areas within a 1-kilometre radius of the blast suffered the worst destruction, structures in the 5 km radius were heavily damaged, and the 10 km radius represents how far damage was reported, such as Beirut’s airport.

In Toronto, if the blast occurred on the waterfront, many of the city’s densely populated neighbourhoods would be affected in some capacity. That includes Danforth Village, Yonge and Eglinton, and High Park.

In Vancouver, should the blast have occurred on the port, the shock wave would have stretched across the Vancouver Harbour and into North Vancouver. The city’s downtown core would be in range to suffer catastrophic damage, as well as popular Granville Island.

- Iran’s unrelenting attacks continue in the Gulf region with no end in sight

- Oil prices jump, U.S. markets retreat as Iran war worsens supply concerns

- Children of some of Iran’s most outspoken regime leaders live in West

- Keir Starmer was warned of ‘reputational risk’ in appointing Mandelson, files show

In Montreal, should such an explosion unfold near the St. Lawrence River, historic neighbourhoods could have been wiped out, including buildings like the Notre-Dame Basilica of Montreal and the Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours Chapel.

However, these maps are just an estimation.

As Joanna Merson, a cartographic developer at the University of Oregon, pointed out on Twitter — topography plays a part in mapping such events. The scope and severity of the damage may vary depending on the natural and artificial physical features of an area.

Merson used a coastline or an uphill area as an example of what might impact the speed of the shockwave. Areas with densely packed high-rise buildings might also be able to cushion the blow.

In Beirut, a large amount of the blast radius appears to have been absorbed by the sea.

Investigation and recovery

The investigation into Beirut’s blast is ongoing.

Lebanon’s prime minister said the investigation would focus on the explosive ammonium nitrate stored at the warehouse.

On Friday, Lebanese President Michel Aoun suggested there are two possibilities behind the blast — either negligence with the storage of the materials or an “external intervention” by a missile or bomb. Aoun said he has requested satellite imagery from France to determine if there were any aircraft in the area at the time.

The tragedy is expected to exacerbate Lebanon’s economic crisis, with damage costs soaring past the $5-billion mark.

Meanwhile, search and rescuers continue to come through the rubble searching for victims and survivors.

— with files from the Associated Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.