It might be a while before hockey fans fill the United Center in Chicago again, but when they do they won’t be allowed to wear Indigenous headdresses into the building.

The NHL’s Chicago Blackhawks franchise says it will ban headdresses at games and build a wing at an Indigenous museum in Illinois, following a weeks-long review of its name and logo. The name and logo will not be changing.

The franchise made the announcement on Wednesday, roughly two weeks after Washington’s NFL franchise agreed to drop the name “Redskins,” which is also a racial slur. The Chicago NHL team had pledged on July 7 to review its own branding amid broader conversations about systemic racism in corporate logos earlier this summer.

“Moving forward, headdresses will be prohibited for fans entering Blackhawks-sanctioned events or the United Center when Blackhawks home games resume,” the franchise said in a statement on its NHL-linked website.

“These symbols are sacred, traditionally reserved for leaders who have earned a place of great respect in their Tribe, and should not be generalized or used as a costume or for everyday wear.”

The Blackhawks organization says it came to the decision “after extensive and meaningful conversations with our Native American partners,” in order to “uphold an atmosphere of respect.”

The franchise says it will work to integrate “Native American culture and storytelling” across the organization, and that it will try to be a “beacon” for education about its namesake.

The team is named after Chief Black Hawk, who was the leader of the Sac and Fox Nation in Illinois in the early 1800s. The franchise’s founding owner, Frederic McLaughlin, commanded a machine gun battalion nicknamed for Black Hawk during World War I, according to the team’s history on the NHL website. He applied that name to his NHL franchise when it was founded in 1926.

Get breaking National news

The franchise’s logo has always been a stylized Indigenous man’s head — supposedly Chief Black Hawk’s — in profile, with several feathers in his hair.

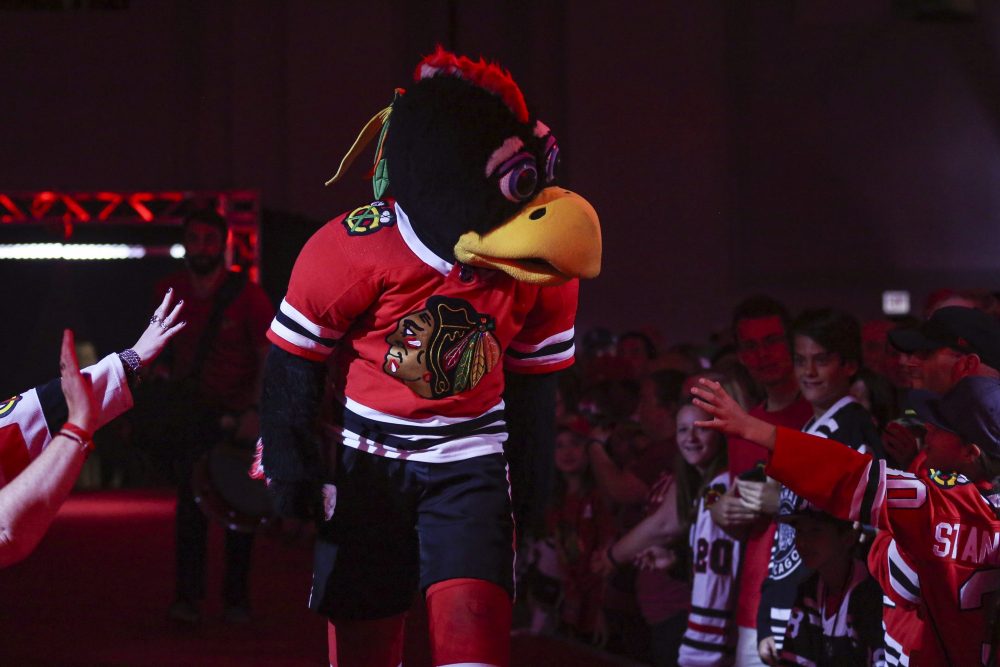

The team’s mascot, Tommy Hawk, is a black bird named after a weapon associated with Indigenous people.

The Blackhawks say they are working to establish a “state-of-the-art new wing at the Trickster Cultural Center, the only Native American owned and operated arts institution in the state of Illinois.” The facility is run by Joe Podlasek, who has worked with the team over the last decade to promote cultural education. Podlasek is of Ojibwe and Polish origin.

“So proud to stand with the Chicago Blackhawks with so many other American Indians!” the Trickster Cultural Center tweeted earlier this month.

The team said earlier this month that it would not change its name or logo.

“We celebrate Black Hawk’s legacy by offering ongoing reverent examples of Native American culture, traditions and contributions, providing a platform for genuine dialogue with local and national Native American groups,” it previously said.

“We recognize there is a fine line between respect and disrespect, and we commend other teams for their willingness to engage in that conversation.”

The Blackhawks are one of several sports franchises named for Indigenous people that have faced accusations of racism over the years. Washington’s NFL team bore the brunt of that criticism until it dropped the “Redskins” name earlier this month, amid pressure from many of its wealthy sponsors. The CFL’s Edmonton franchise also dropped its “Eskimos” name amid similar criticisms.

The MLB’s Cleveland Indians have also said they will review their name. The Atlanta Braves have said they will not change the name of their baseball team, although they have pledged to review their fans’ “chop” celebration.

The Chicago Blackhawks announced their decision ahead of the start of the NHL post-season, which has long been postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic. The league has isolated 24 teams at two hub locations in Edmonton and Toronto, where they will play without fans in the stands.

The Blackhawks will face the hometown Edmonton Oilers in a best-of-five play-in round beginning this weekend.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.