If Canadians want a full economic and social recovery from the coronavirus pandemic, child care is key.

That’s the message from the authors of a new report published Tuesday by the Institute for Gender and the Economy at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, in partnership with YWCA Canada.

The report proposes what it calls a “feminist recovery plan” for the country and highlights the critical need for a focus on ensuring no workers are sidelined in the recovery from a pandemic economic and health crisis that data shows has hit women and vulnerable communities harder than men.

“Without attention to inequity in post-pandemic recovery, a potential decline in our achievements is a real threat, given the gendered economic, health and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic across all aspects of society,” the report’s authors state.

“In the past few decades, Canada has made major strides towards a more gender-inclusive workforce … but systemic barriers still exist—and the first phase of the pandemic’s economic downturn has shown that gender inequities are influencing who is bearing the brunt of the pandemic’s effects.”

“What lies before us is an opportunity to re-imagine our future.”

Tammy Schirle, a professor of economics at Wilfrid Laurier University and also a working mother navigating the same challenges the report lays out, says its focus on child care is critical.

“Women, I think, are faced with some very unique challenges when it comes to recovering from this pandemic,” she said.

“When we look back at who lost jobs between February and April, there are about five and a half million men and women who lost jobs but for most men, that was a very short term crisis. They work in places like construction. They lost a lot of jobs in April, but they quickly rebounded in May.”

That wasn’t the case for women, Schirle explained.

Get breaking National news

“They lost a lot of jobs right away in March in those first shutdowns working in things like accommodations and food services and entertainment and recreation and a lot of their jobs haven’t come back yet,” she said.

“So women generally have been hit harder by this crisis. Now, moms end up with this very unique challenge of not only trying to find a job again, but just getting to work while the kids are still being taken care of.“

The economic crisis sparked by unprecedented social shutdowns in a bid to limit the spread of the coronavirus has been frequently dubbed a “she-cession.”

Shelter-in-place orders and social lockdowns have devastated many of the industries where women make up the largest proportion of workers: the service sector, hospitality and care-giving among them.

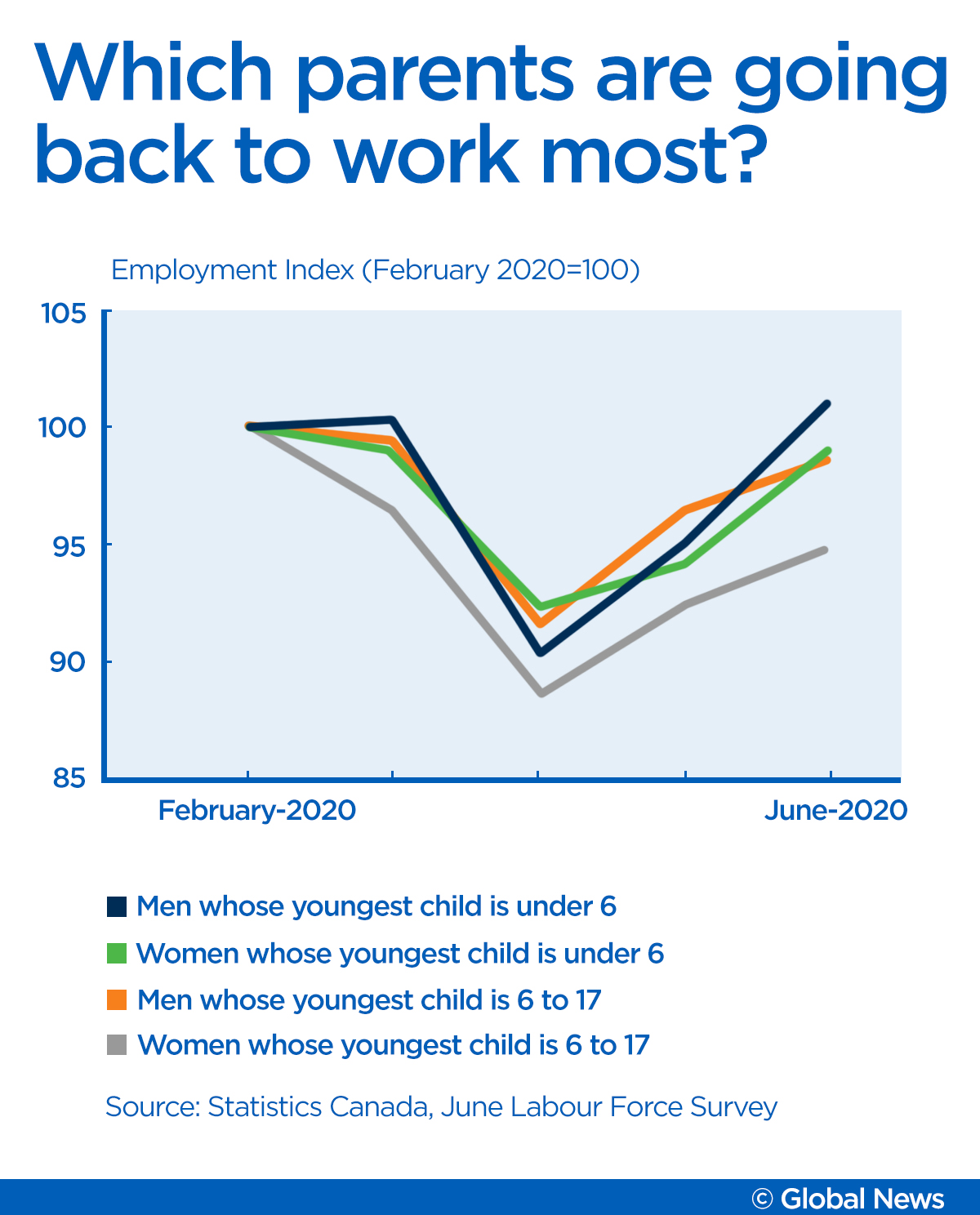

And for women with children in particular, the gradual return to work now taking place across the country is taking place more slowly than for men with children.

The June labour force survey from Statistics Canada showed that while the return to pre-COVID-19 employment is picking up, more women than men with children under the age of 18 reported working less than half their usual hours.

For men with kids under 18, 8.7 per cent said they worked less than half their usual hours in June. Among women, that number jumped to 14.3 per cent.

Within that category of parents with children under the age of 18, women whose youngest child was between 6 and 17 years old were returning to work at the lowest numbers compared to other parents.

The federal data agency said the trend is one that it plans to watch carefully, especially with the gradual reopening of some schools a possibility this fall.

“As the easing of COVID-19 restrictions continues in the coming months, and as children aged 6 to 17 begin to return to school in September, the ability of mothers of these children to return to pre-COVID-19 employment levels will be of particular interest to monitor,” the data agency said.

While some child care facilities have been allowed to reopen, not all can do so at full capacity, and others have shut down entirely because of the lockdown’s financial impacts.

The federal government announced last week some $625 million in support for the provincial child care sectors, billing it as a way to help stabilize an industry hit hard by the shutdowns and one that is key to allowing workers to return to their roles, or seek new work.

But that’s already been criticized as not enough and the report authors urged officials to allocate more money to a cohesive strategy to roll out more child care availability.

The report lays out recommendations including allocating at least one per cent of GDP to child care and early education, creating a National Child Care Secretariat and coordinating the reopening of schools and child care with any economic reopenings.

Schirle said successive governments and businesses have traditionally looked at child care as something distinct from the infrastructure designed to support the economy.

She said the pandemic’s hit on women and working mothers shows that view needs to change — now.

“We really need to start thinking of child care as part of a care-giving infrastructure that is supporting our labor market. I think we have this very old model in mind where we had a decentralized way of offering child care,” she said.

“When we’re talking about 15 per cent of our workforce having to juggle work and kids, that’s not a small segment of our workforce anymore. So it is a much bigger part of our economy than it used to be and I think people need to really wrap their head around that.”

Comments