Police in Ontario shot 62-year-old Ejaz Choudry in his home. In New Brunswick, they shot Chantel Moore in her home and Rodney Levi at a friend’s barbecue. Prior to that, Regis Korchinski-Paquet fell from her balcony in Toronto while police were in her apartment. All four have died in the last six weeks; police called not because they committed crimes, but to check on their well-being.

Amid national and international reckonings over racism and police brutality, there have been widespread calls to use mental health practitioners — not cops — in moments of crisis. But while mental health is just one aspect of overall health (albeit a very important one), Canadian health care is not immune to the systemic racism impacting the country’s police forces.

Experts say that’s evident in a myriad of ways, from the coronavirus pandemic’s disproportionate impact on Indigenous people and Black people to other, non-COVID-19 headlines.

In Alberta, the minister of health recently ordered an independent investigation into the health authority’s handling of a noose taped to an operating room at the Grande Prairie Hospital in 2016. In B.C., the province is looking into allegations that some staff have been engaging in a racist game of what’s-the-blood-alcohol-level of the (primarily) Indigenous patients who come to them seeking care.

But where defunding the police is an option, defunding health care is decidedly not. Nor, says Dr. Suzanne Shoush, does adding more Black, Indigenous and other racialized health-care providers solve the problem on its own — you have to change the system.

Like policing, health care’s racism problem is systemic, says Shoush, who is a Black Indigenous doctor of Sudanese and Coast Salish heritage and the Indigenous health faculty lead for the University of Toronto’s family and community medicine department. Much like policing, she says, tackling it will require facing up to some uncomfortable truths.

“It really all has to do with the blindness of privilege. People who have privilege are really, really blind to the fact privilege plays a role in where they are today.”

***

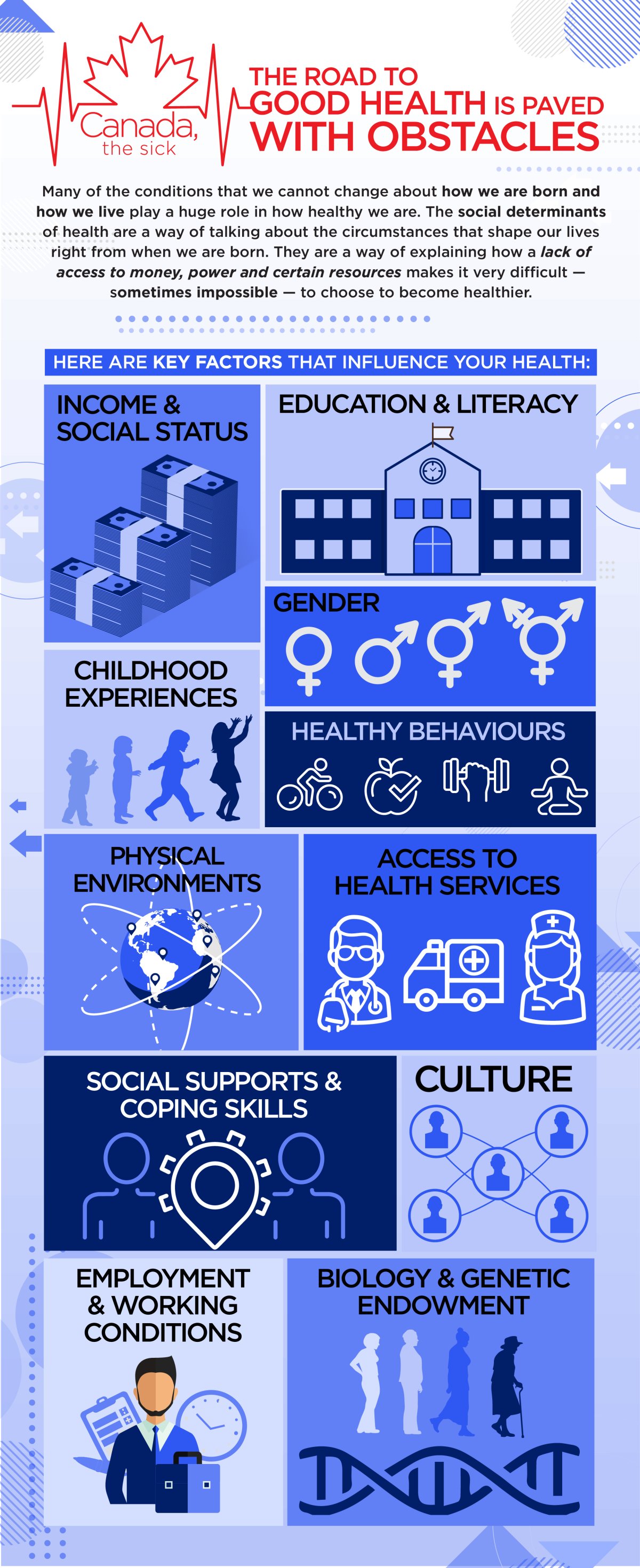

Start with the social determinants of health: key factors that contribute to how healthy you, as an individual, are, as well as the group of people living around you.

Some you can control (to a degree), others you cannot: income and social status, employment and working conditions, education and literacy, childhood experiences, physical environments, access to health services, biology and genetic endowment, gender, culture, race and racism, and historical trauma.

These factors merge together, making Indigenous people among the highest-risk groups for diabetes and complications from diabetes, over-represented in HIV infection cases, tuberculosis cases and sexually transmitted infections, with a stroke rate nearly twice as high as non-Indigenous Canadians’ and a suicide rate among First Nations youth five to seven times higher than their non-Indigenous peers.

For Black people in Canada, the data is harder to come by (a factor experts say serves to worsen Black health). But a research review from the Wellesley Institute, a non-profit that seeks to improve health equity in the Greater Toronto Area, indicates Black people’s health is harmed in part because they live in a racist environment. Much like Indigenous people, any racism experienced during their interactions with the system impacts their access to future care.

Furthermore, statistics compiled by the Black Health Alliance reveal that Black people make up 18 per cent of Canadians living in poverty even though they only represent less than three per cent of the total population. In Ontario, the risk of psychosis for people of Caribbean, East African and West African origin is 60 per cent higher than for others. And the likelihood that breast cancer kills Black women is 43 per cent higher than for white women.

Epidemiologist Nancy Krieger boils it down to six pathways through which racism harms a person’s health, including economic and social deprivation, socially inflicted trauma, inadequate or degrading medical care, and ecosystem degradation and alienation from the land — the latter a recurring theme in reports like the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

“When you are displaced, you are not healthy,” says Shoush, who recently wrote about how Canada was founded without the consent of Indigenous and Black people.

Get weekly health news

“When we have a society that reflects and was founded in a non-consensual relationship, it’s very displacing, and this is why we see huge disparities in wellness, in health, chronic disease, life expectancy, child poverty.”

***

Where some Indigenous people in Toronto will not consider going to the doctor, they might consider chatting with Cheryllee Bourgeois. They see her, after all, with her three children out in the community, at a powwow, at Thursday night socials at the Native Centre.

Bourgeois is an exemption Métis midwife working with Seventh Generation Midwives Toronto, as well as a professor in Ryerson University’s midwifery education program. She became the city’s first exemption midwife in 2018, following in the well-trodden footsteps of exemption midwives in Six Nations in southern Ontario.

Working under the exemption allows registered midwives (Bourgeois was one for more than a decade) to provide a broader scope of care to their clients — to do Pap tests, address sexual and reproductive health and provide other health care not confined to pregnancy and the first six weeks of a baby’s life.

The job itself is a tacit reminder of systemic racism in health care and recognition that increasing Indigenous access to health care involves community accountability and acknowledging Canadian history.

“The health-care system was a very critical, key piece of the whole colonial history of the subjugation of Indigenous people,” Bourgeois says.

“There were such things as Indian hospitals where you were provided substandard care and where you were not allowed to go to the mainstream hospital.”

Even now, it doesn’t matter if Indigenous people give birth in rural, remote or urban settings in Canada, she says, their outcomes remain the same.

“So that leads to something deeper, which is this very pervasive and strong systemic racism that exists within the system, affecting health outcomes,” she says. In other words, it’s good to look at improving access, but if that’s the sole focus of change “then it doesn’t actually solve the problem.”

But Bourgeois’ patients grow by word of mouth, so-and-so telling their aunt or brother or cousin or friend “you’ll be treated well there.”

When the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic struck Canada this spring, Bourgeois and Shoush started Call Auntie, an information hotline for Indigenous people to ask their COVID-19 questions. In only a few short months, it’s morphed into something more.

It’s a form of accountability, Bourgeois says — health-care workers can call ahead to certain testing centres to let them know an Indigenous person is incoming, a “warm referral.” Some people also ask about how to apply for the Canada Emergency Response Benefit or how they can get food delivered to their house because they have a compromised immune system.

Sometimes, Bourgeois says, people just want to talk through their concerns with a supportive listener. It isn’t always about COVID-19. People call to say they’re living on the street — Black people and Indigenous people are over-represented in Toronto’s homeless population — and they’re scared of going to a shelter, so what can they do?

It’s low stakes, Bourgeois says, because nothing they ask will get them put “on a list of trouble clients.”

They want to keep the line going after the pandemic.

“For the Indigenous community, there is literally — I don’t want to say zero… but really, there’s zero trust in the health-care system that they’re actually going to be able to give them what they need,” Bourgeois says.

“In pain? Labelled as drug seeking. Having a trauma response to something? You’re non-compliant. Treated badly so you don’t go to your next appointment? You’re kicked out of care.”

It’s about so much more than extra funding, she says, because the current funding models don’t take into account that need for community accountability — the need for health-care providers like Bourgeois, who deliver babies, give people birth control shots, answer the questions people are scared to ask and then bring their children to Thursday night socials.

“When health care your whole life has basically worked against you, you’re going to do everything in your power to avoid it,” she says.

“You’re really not going to do anything if you don’t change the system… If you actually want to see a change in outcomes or a change in people engaging, you need to build trust.”

It’s important to remember that equitable access is not the same as equitable outcomes, says Kwame McKenzie, CEO of the Wellesley Institute, but he thinks people spend a lot of time thinking about the former rather than the latter.

What’d he like people to think about is: “if everybody gets the same service, is the outcome the same? And is giving everybody the same service a reasonable thing to do?”

Take something simple like treating high blood pressure, McKenzie says. One size does not fit all because the commonly used drugs do not work well for people of Caribbean and African origin. In other words, he says, equal access might be the same drug for everyone but it won’t translate into equal outcomes.

“Outcomes can be not as good because the intervention is the wrong intervention and you need a completely different intervention for different groups,” he says.

“You need a system that interacts with the social determinants of health because both your risk of illness and chance of getting better are very linked to who you are, how you live, what your income is.”

***

More than a decade before health-care workers in British Columbia allegedly made a game out of guessing the blood alcohol levels of (predominantly) Indigenous people seeking care, Brian Sinclair was ignored to death in a Winnipeg ER in September 2008 — presumed to be “another drunken Indian” rather than a 45-year-old with a severe bladder infection.

“Sinclair was not ill but simply sleeping or intoxicated. This assumption, made and remade over and over in the 34 hours while Sinclair sickened and died in a hospital ER, is a striking and painful example of one of the structures of indifference that cost Brian Sinclair his life, as it has cost the lives of other Indigenous people in Canadian cities,” wrote Mary Jane Logan McCallum and Adele Perry in their book Structures of Indifference: An Indigenous life and death in a Canadian City.

It isn’t that people don’t recognize when things are problematic, Shoush says — they do, and that realization isn’t new. She thinks here of the Jane Elliott clip that’s been circulating on social media.

In it, Elliott, a diversity educator, asks a room full of white people in the 1960s to please stand if they’d like to be treated the way Black people are treated. Nobody stands. She asks again. Nobody stands.

Then, she tells the room, “That says very plainly that you know what’s happening, you know you don’t want it for you. I want to know why you’re so willing to accept it or to allow it to happen for others.”

Decades later, Shoush says more people are starting to understand how the structure of systems — be it child apprehension, policing, incarceration or health care — impacts individual outcomes, but more is needed.

“We understand that there are deep, deep injustices in our culture, in our society, but we always say that they should somehow pull themselves up, we should pull ourselves up by the bootstraps, not realizing that some people have been resourced from birth,” she says.

“That myth of individualism has to be shattered across every aspect of our society.”

— with files from The Canadian Press

The Call Auntie information hotline for Indigenous people is open daily from 4 to 9 p.m. at 437-703-8703. All messages left after hours will be responded to.

Comments