With a growing anti-racist protest movement across North America triggered by the death of Minneapolis man George Floyd in police custody, many Winnipeggers, including some of the city’s well-known figures, are reflecting on their own experiences with racial injustice.

Grand Chief Arlen Dumas of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs told 680 CJOB he first experienced racism as a young child in school.

“The first thing I experienced as a young child was being introduced to what racism was, being called a ‘dirty Indian’ and being called terrible things, and I didn’t really understand what these names were or what it was about, because to me, everybody was the same. We were all kids.

“That was my introduction to that difficult issue. Fortunately, I had supports to help me understand. My grandfather made lots of efforts to help me explain… you’ve just got to keep being strong and keep being a good role model and show everybody the reality of who I was as an individual, as a First Nations person.”

Dumas said the racist taunts served to give him the conviction to prove people wrong, and to defy what people were saying about him.

An assault he experienced while attending university — for no reason other than who he was, he said — furthered his resolve to persevere.

“I think we all, collectively, need to become more aware of (racism) and move things further ahead.

“I don’t think you can walk away.

“I think it’s important to try and give people an opportunity to have an understanding and to try and teach people and create some awareness.

“I find that in my experience… sometimes people would be worried about coming to ask — there was a sense of intimidation, or they were afraid of the fact they were naïve or ignorant about things.”

Dumas said as a father of four children, he realized that to young kids, racism doesn’t exist — which gives him hope for the future.

Get breaking National news

“When you see little children playing, everybody’s the same,” he said.

“Racism and ignorance are things that are taught to people, and the more we work together, I think it’s reasonable to believe we can coexist.

“We’ve just got to make sure we teach our children and make them aware of these things so they don’t learn these behaviours.”

Winnipeg lawyer Priti Shah, CEO of Praxis Conflict Consulting, told 680 CJOB she, too, faced racism from a young age in school.

“It was very obvious to us in school that we were different, and that at times we were singled out. Our family communities were very diverse, but whenever we were dealing with other institutions, people just didn’t look like us and we were often singled out.

“That always gave a feeling of being set apart from everyone else and somewhat isolated and introspective about your experience.”

Shah said she’s experienced systemic racism throughout her adult life as well, even as a respected lawyer.

“We, as lawyers, are charged with upholding people’s rights, but within the organization, once you become a person who speaks on equality and diversity, you get pigeonholed in that area and aren’t seen to be capable to lead in any other department,” she said.

“What happens is there are biases within the system, within the questions, within the mechanisms that perpetuate the same decisions, the same choices being made.

“It is a constant feeling that you’re not seen… I had a church leader a few weeks ago say, ‘We didn’t even notice that you’re a visible minority,’ and I almost didn’t know how to act.”

Shah said people need to want to see things differently, but unfortunately, if the system is working in their favour and they’re part of the majority, many are uncomfortable pushing for change.

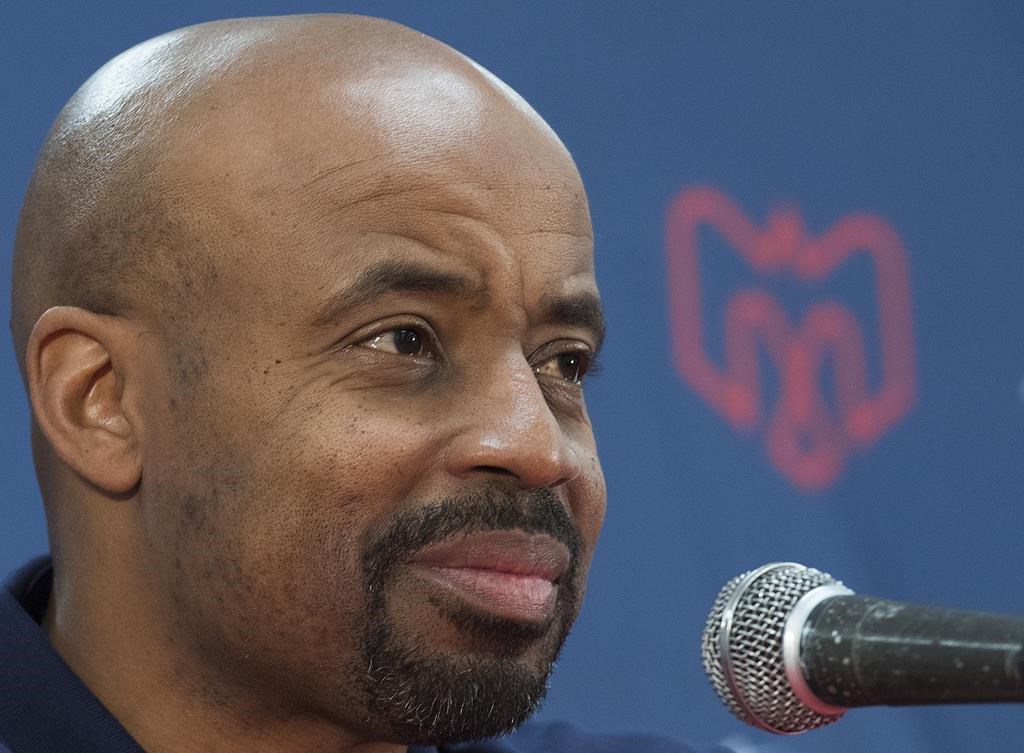

Currently in the role of head coach for the CFL’s Montreal Alouettes, former pro quarterback Khari Jones was a fan favourite in Winnipeg, leading the Blue Bombers to the Grey Cup final in 2001.

Jones told 680 CJOB that his early years in California were “as idyllic as you would find” and that he didn’t start experiencing racism until he was older.

“It was when I got to college that I felt it a little bit at times, and even at the professional level and, of course, when me and my wife decided to get married,” he said.

“There were a lot of worries about being in an interracial marriage.

“There have been a few cases — nothing crazy — being in Canada and maybe being who I’ve been up here as someone people know, we haven’t felt a lot of racial divide, but there has been some. When I was playing there, there were letters that were coming into the team and to myself that were threatening in nature and very racist.”

Jones said he kept the offensive letters and recently took them out for the first time in years, inspired by his emotional reaction to the Floyd protests in the United States.

“They’re very horrible, as far as talking about me, my wife, and my child that had just been born, in about the worst terms you can talk, and there were threats in there.”

Jones said his daughters — one of whom was born in Winnipeg — have had a good experience growing up in Canada, due in part to the diversity of locations his football career took the family.

“My girls have had a pretty good upbringing. Because we’ve moved around a lot, and we’ve lived all over the map, they’ve had kind of a different upbringing. They’ve dealt with a lot of different people and a lot of different places, and I would say their experience has been pretty good here.”

Comments