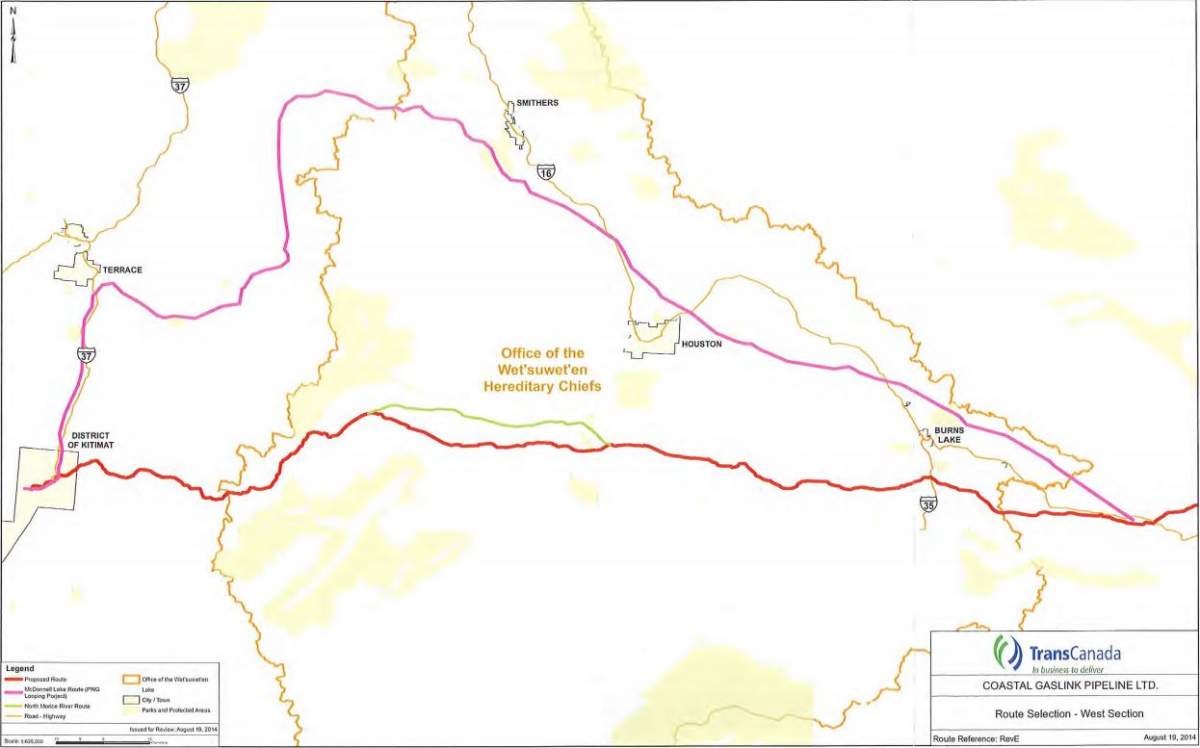

The $6-billion, 670-kilometre Coastal Gaslink pipeline is set to run near Dawson Creek, B.C., to a planned LNG export facility in Kitimat. The Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs oppose the project because the 190 kilometres of the pipeline is set to run through their traditional territory.

The clan chiefs say the pipeline cannot proceed without their consent. The quarrel has sparked solidarity protests across the country, leading to blockades on railway tracks and other demonstrations.

During the early planning stages of the pipeline, Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs offered an alternate route, but Coastal Gaslink deemed it unacceptable.

Here’s a look at how the pipeline route was decided and what the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs proposed:

How did Coastal GasLink choose the route?

On its website, Coastal Gaslink offers a timeline of what was done to select the route.

- Here’s what we know about the Tumbler Ridge mass shooting investigation

- B.C. 2026 budget ‘neither’ big cuts nor tax increase, minister says

- Former Conservative leader John Rustad says he’s not running for his old job

- Parts of B.C.’s South Coast set to see snow-rain mix with ‘rapidly changing’ travel conditions

It says the final route was only chosen after years of study and consultation with affected First Nations communities.

The company claims it spent more than 100,000 hours of field work and study “to determine the most feasible route” to install the 48-inch diameter gas pipeline. Once that was complete, the company applied and granted an environmental certificate from B.C.’s Environmental Assessment Office (EAO).

Coastal Gaslink then secured approvals from 20 other First Nations communities along the final proposed route, including the Wet’suwet’en elected band councils.

Discussions with the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs — who are the crux of the pipeline’s opposition — began in 2012.

Coastal Gaslink described the consultations as “limited in scope and scale” compared to the talks had with other Indigenous communities. The company suggested that the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs exhibited an “unwillingness to engage.”

David Pfeiffer, the president of Coastal Gaslink, said a number of alternate routes were analyzed after receiving feedback from affected First Nations communities and leaders, including the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs. He told reporters on Jan. 27 that the final route selected was the “most technically viable” and had the “least environmental impact.”

Get daily National news

In May 2016, the company amended one route, the “South of Houston Alternate Route,” by “incorporating feedback” from local Indigenous communities. It runs about 3.5 kilometres south of the original one and was approved by the EAO.

What is Wet’suwet’en proposing instead?

The Office of the Wet’suwet’en proposed its alternative — the so-called McDonnell Lake route — during the early stages of the pipeline.

The route would move a segment of the pipeline around the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chief’s territory.

While part of it would still run through their traditional land, it would skirt past culturally important areas, snaking farther north, nearer to Smithers, B.C.

Why is it not “feasible?”

In a letter to the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs, sent on Aug. 21, 2014, Coastal Gaslink laid out a number of reasons for rejecting the alternative route. Portions of the letter were published in part on the company’s website on Feb. 14.

The reasons include:

- The proposed path would need to cross eight additional rivers.

- It would increase the length of the pipeline by 77 to 89 kilometres, increasing what the company calls “environmental disturbance.”

- In certain areas, the 48-inch pipeline “could not physically be constructed” at all, meaning “deviations” would be necessary for as much as 40 per cent of the proposed route.

- The pipeline — specifically the McDonnell Lake portion — would be built even closer to the B.C. communities of Houston, Smithers, Terrace and Burns Lake, which the company claims could bring with it more disruption and safety concerns, although unspecified.

Coastal GasLink says the changes would increase capital costs by as much as $800 million and delay the project by one year.

The alternate route would also result in a “reduction in economic benefits” for the Wet’suwet’en people, according to the company.

The reasons for the rejection were listed briefly in a December 2019 injunction by the B.C. Supreme Court, which cleared the way for Coastal GasLink to continue work on the project.

Impact of route choice a ‘trade-off’

The decision-making process behind a massive project like the B.C. pipeline requires extensive evaluation on multiple fronts, according to Graeme Norval, an engineering professor at the University of Toronto. But, in contesting situations, especially ones with two large stakeholders, big finals decisions often come down to a trade-off of sorts, Norval said.

“We need to remember that not ‘feasible’ and not ‘possible’ are different.”

“If we think about Route A and Route B — one is longer than the other. This means more land to disturb. It makes river crossing more complex. Route B is closer to several communities. So, while both routes are possible, you are trading off between the people impacted and the amount of impact.”

Norval used municipal traffic changes in big cities as an example of the “trade-off,” such as a pilot project on King Street aimed at increasing public transit right-of-way. While it was successful in reducing congestion on the busy downtown street and cutting streetcar commute times, some business owners located on the street claimed it slashed their business.

While not a full-proof comparison, Norval said it’s an example of the “difficult discussions” that need to be had in big projects affecting different groups.

“It’s even more difficult when we accept that there have been many discussions and agreements created, prior to the start of the construction,” he said.

“The question is — how do we get people to speak with each other and listen to each other? Then we need to find some compromise that everyone can accept.”

The Canadian government is grappling with that now. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is under increasing pressure to end the blockades. While multiple levels of government have offered to meet with the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs to discuss a way forward, it has not yet been agreed upon.

— With files from Global News’ Sean Boynton and The Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.