The company behind a contentious pipeline in northern B.C. says building through traditional Wet’suwet’en territory was the most feasible way forward for the project.

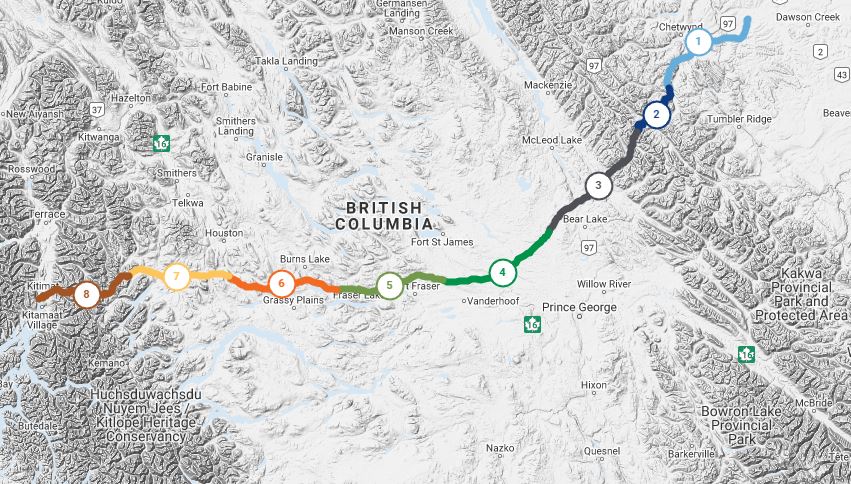

Coastal GasLink’s approved 670-kilometre route from west of Dawson Creek, B.C., to a planned LNG export facility in Kitimat has come under scrutiny as protests spread across the country in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs opposed to the project.

Before and after the RCMP enforced a court injunction against the chiefs and their supporters who were blocking access to a construction site near Houston, B.C., many protesters and politicians suggested an alternate route proposed by the chiefs and rejected by the company could have avoided the years-long dispute.

In a statement posted to its website Friday, Coastal GasLink made clear that the final route was only selected after years of study and consultation with local First Nations along that route.

Coastal GasLink says it spent more than 100,000 hours of field work and study “to determine the most feasible route to install our 48-inch diameter gas pipeline” before applying to B.C.’s Environmental Assessment Office (EAO) for an environmental certificate in 2014.

The company also secured approvals from the Wet’suwet’en elected band councils and 20 others along the final proposed pipeline route.

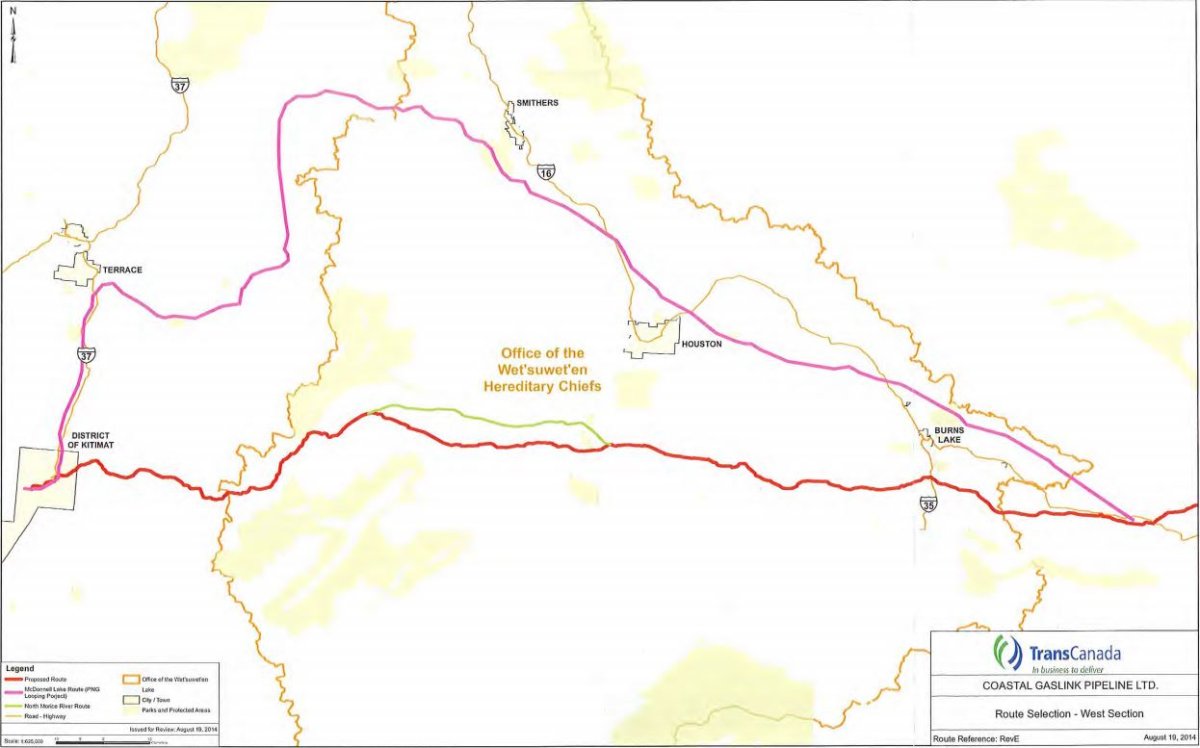

Throughout that time, the company says it was unaware of the alternate route proposed by the Office of the Wet’suwet’en: the so-called McDonnell Lake route that would travel north around the traditional territory before heading back south to Kitimat.

The office’s natural resources department disputes that claim in a 2014 report to the EAO, saying its recommendation of the alternate route was “unsuccessful” throughout two years of negotiations with Coastal GasLink.

“The Wet’suwet’en view this as a loss of co-operation by the proponent, which demonstrates a disregard for Aboriginal rights and title,” the report reads.

Lawsuits filed against Coastal GasLink also point to this rejection as the moment relations soured between the two sides, forcing the hereditary chiefs to dig in and refuse to give consent.

The Office of the Wet’suwet’en was not available to comment on the proposed alternate route ahead of this story being published Sunday.

In its statement, Coastal GasLink says the Office of the Wet’suwet’en met with the company in May 2014 — four months after the application to the EAO was submitted — and expressed their preference for the McDonnell Lake route, which would roughly follow the route of the existing Pacific Northern Gas pipeline used for residential and commercial gas deliveries.

The company says it studied the proposed route and determined it was not feasible for multiple reasons, which were submitted to the Office of the Wet’suwet’en in an August 2014 letter recently made public on the company’s website.

Among the reasons given were an additional eight river crossings, the inability to build a 48-inch pipeline through some areas along the route, an additional 77 to 89 kilometres of “environmental disturbance,” and “a reduction of economic benefits for the Wet’suwet’en people.”

The new route would have also cost the company an additional $600 to $800 million along with a year-long delay, which “negatively impacts the viability of the LNG Canada project.”

Additionally, “the pipeline would be constructed in close proximity to the communities of Houston, Smithers, Terrace and Burns Lake, which would preferably be avoided for construction disruption and operational safety reasons.”

As a compromise, Coastal GasLink suggested to the hereditary chiefs that 55 kilometres of the pipeline be moved three to five kilometres away from the Unist’ot’en healing centre, which sits near the worksite being disputed by the chiefs and their supporters.

The company says the chiefs did not give a response either way to the proposed North Morice River Route. An invitation to the chiefs to fly over the proposed alternate routing to see for themselves was also not returned.

Following a visit to the Gidimt’en clan’s camp outside the Coastal GasLink worksite in January, Nanaimo-Ladysmith Green MP Paul Manly issued a statement accusing the company of ignoring the hereditary chiefs’ requests for an alternate route.

“The Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs provided alternative routes to Coastal GasLink that would have been acceptable to them as a pipeline corridor,” Manly said.

“Coastal GasLink decided that it did not want to take those acceptable options and instead insisted on a route that drives the pipeline through ecologically pristine and culturally important areas.”

Former Green Party leader Elizabeth May was included in that statement decrying government actions in support of the project, which she said “demonstrate complete disrespect for the constitutional role of the hereditary chiefs in the management of their land.”

The former MP for the region, Nathan Cullen of the NDP, has repeatedly raised the question of why an alternate route wasn’t approved.

The Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs claim authority over rights and title to land that was never covered by treaty, while elected councils only have jurisdiction over First Nations reserves.

The dispute over who has final say on the $6.6-billion Coastal GasLink project has sparked Canada-wide protests in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs and their supporters, which have shut down rail and port activity particularly in Ontario and B.C.

The hereditary chiefs have since launched a legal challenge against the EAO’s approval of the project, arguing it fails to incorporate the findings of the inquiry on missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls by placing construction “man camps” near communities on traditional lands.

The complaint also accuses the EAO of not considering the facts when granting an extension of the company’s environmental certificate, including Coastal GasLink’s alleged “non-compliance” of conditions that were part of the original certificate.

Comments