The way you dress can have an effect on whether or not people think you’re competent, a new study suggests. Researchers said these judgments take place in a matter of milliseconds.

The study was conducted by researchers at Princeton University and was published in the Nature Human Behaviour journal on Monday. It aimed to show how something as nuanced as the subtle economic status cues in clothes can impact perception.

“Your snapshot judgments of competence, even when you don’t know the person at all can predict a lot of important social outcomes, like who becomes a CEO of a big company and who doesn’t,” DongWon Oh, lead author of the study, said in an interview.

“We found the economic cues are really hard, if not impossible to ignore.”

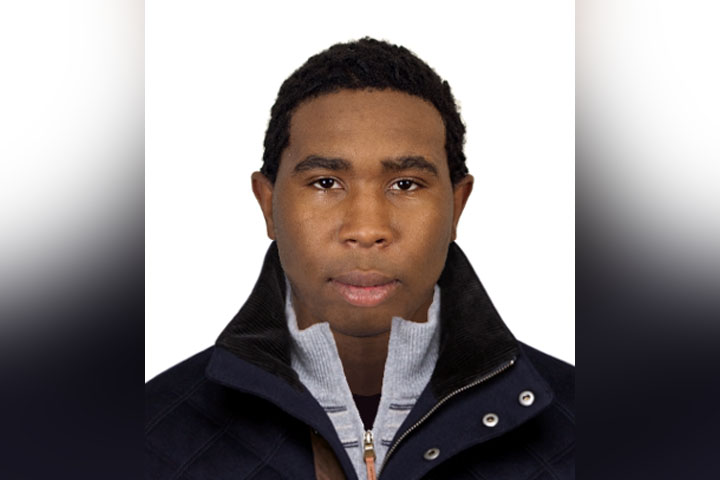

Oh and team started the experiment with images of 50 people’s faces. They were each wearing clothes rated as “richer” or “poorer” by an independent group of judges who were asked, “How rich or poor does this person look?”

Based on those ratings, the researchers selected 18 black and 18 white subjects displaying the most prominent rich-poor differences. Those images were then used across nine slightly tweaked versions of the same study.

Study participants were asked to rate the competence of faces shown in photos.

Regardless of what was worn in the images, researchers found that clothing perceived as “richer” by a participant led to higher competence ratings of the person pictured than similar clothes judged as “poorer.”

The bias shown adds “yet another hurdle to the challenges faced by low-status individuals,” the study said.

Participants saw the images for three different lengths of time, ranging from about one second to approximately 130 milliseconds.

Get daily National news

Their reactions were “non-deliberate, and triggered by brief exposure,” researchers said.

Several studies included modifications to the original design.

In some iterations, they replaced all suits and ties with non-formal clothing. In others, they told participants there was no relationship between clothes and competence.

In one study, the researchers provided information about the person’s profession and income to minimize potential inferences from clothing.

In another, they expanded the participant pool to nearly 200, and explicitly instructed participants to ignore the clothing.

Regardless of these changes, the ratings remained consistent. Faces were judged as significantly more competent when the clothing was perceived as “richer.”

Oh said there were limitations to the study.

“This is a very controlled situation where you only see the visual images and it’s a static image, so it’s pretty stripped out,” he said.

Oh said results could differ drastically in real-life situations where someone had previously heard about a person from a friend, read about someone’s accomplishments online or were forced to spend longer amounts of time with them than allotted in his study.

They also found that physically attractive people were viewed as more competent, which affected the way Oh’s team selected their subjects.

Understanding how to reverse these biases, however, will take more time and research.

Determining why certain types of clothes are viewed as “richer,” how facial features factor in, and how individuals come to these conclusions will need to be examined, said Oh.

But in a world where Instagram and Facebook can act as the first impression, making such judgments may be difficult to unlearn.

“Under certain circumstances, where you only see photos of other people in either richer versus poor-looking clothes, it seems very hard to reverse these kinds of biases,” said Oh.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.