This the second in our series of stories on temporary emergency room closures in Nova Scotia. To check out the rest of our CODE ZERO series, click here.

As Nova Scotia’s premier walks to the podium, he’s assailed by a mixture of boos and applause.

It’s June 25, 2018, and although his Liberal Party won a strong majority just over a year ago, Stephen McNeil is not on friendly ground.

He’s forced to adjust the microphone for his 6’7″ frame and raise his voice in an attempt to drown out the ongoing heckling

McNeil — along with then president and CEO of the Nova Scotia Health Authority (NSHA) Janet Knox, then-minister of Municipal Affairs Derek Mobourquette and Business Minister Geoff MacLellan — are in Sydney, N.S., to announce a series of sweeping changes to health care in Cape Breton.

READ MORE: Temporary emergency room closures on the rise across Nova Scotia

As the premier and his entourage detail how the Northside General Hospital in North Sydney and the New Waterford Consolidated Hospital in New Waterford will be permanently closed, the shouts of “shame” and “traitor” continue to rain down.

The news that the beds and resources will be shifted to a revitalized Cape Breton Regional Hospital in Sydney and an expanded Glace Bay Health Care Facility in Glace Bay does not make anyone in the room happier.

By the time he walks off the stage, McNeil is shouting into the microphone.

Increasing closures, more frustration

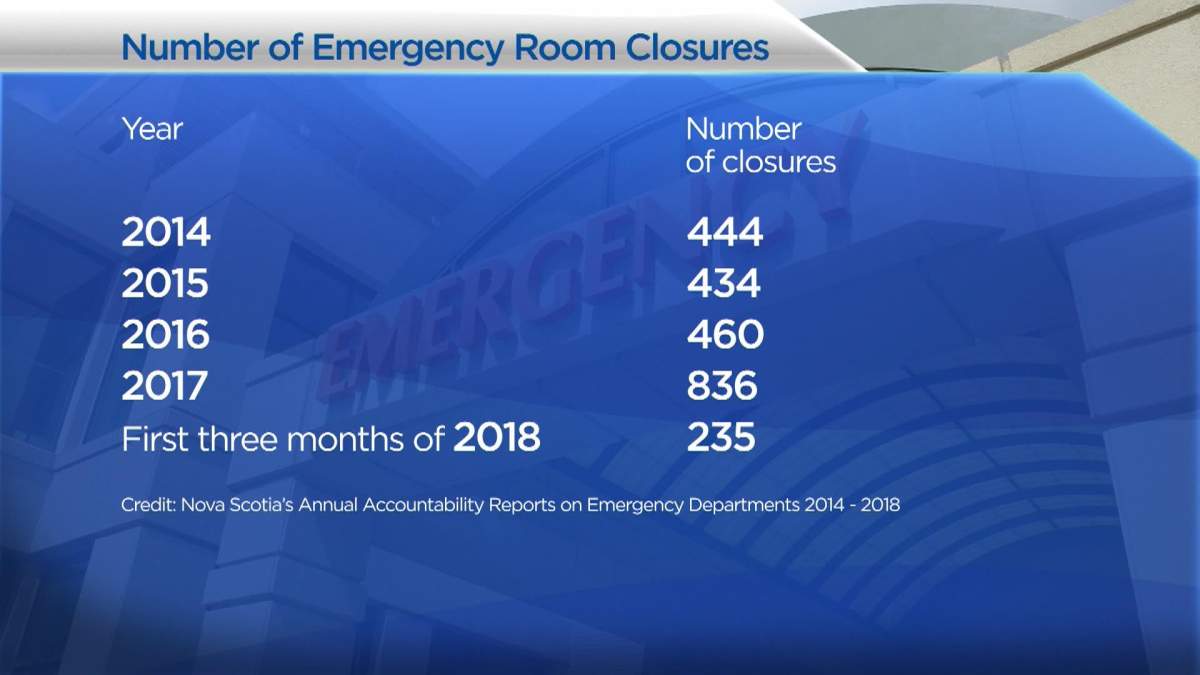

Only six months before McNeil made his trip to Sydney, the province had hit an alarming statistic. The end of 2017 saw ERs across Nova Scotia close a total of 836 times, according to data collected from reports prepared by the Nova Scotia government.

Nowhere has been harder hit than the Glace Bay Health Care Facility, which between 2014 and the first three months of 2018 was closed 364 times.

Found in a town of fewer than 20,000 people on the north-eastern shores of Cape Breton Island, the hospital has borne the brunt of a measure which Barb O’Neill, the emergency program of care director in the NSHA’s eastern zone, said is meant to compensate for a shortage of doctors and nurses.

Get weekly health news

“The department closures in this area are related to physician vacancies,” said O’Neill.

Sometimes those closures can come with as little as a half a day’s warning.

For employees, that means completing their shift at the Cape Breton Regional Hospital, roughly 25 minutes away.

“You’re robbing Peter to pay Paul continuously,” said Dr. Margaret Fraser, president of the Cape Breton Medical Staff Association.

“When I started here, we staffed North Sydney 24/7. Glace Bay 24/7. New Waterford 24/7 and Sydney 24/7. We are now at the point where we can barely keep the regional going.”

READ MORE: 6 N.S. emergency departments will be closed at some point this week due to doctor shortages

Patients left ‘incredibly frustrated’

Fraser has been working in the Cape Breton health-care system for more than 10 years.

She said that patients are “incredibly frustrated” with the state of health care in Cape Breton and the increase of temporary ER closures isn’t helping.

“The waits are hours long and it certainly shows the patients are increasingly impatient with that. And often by the time you get to see somebody, they’re very angry,” said Fraser.

It’s a sentiment echoed by Coun. Amanda McDougall of Cape Breton Regional Municipality.

Glace Bay is part of her district and McDougall said that her constituents don’t want to go to the Cape Breton Regional Hospital because they know that the hospital will be overwhelmed dealing with patients who have come from North Sydney or New Waterford when their ERs have closed.

In the four years of data analyzed by Global News, the Northside General Hospital in North Sydney and the New Waterford Consolidated Hospital in New Waterford were closed 223 times and 179 times, respectively.

Although the reports analyzed by Global News only provide data up to March 2018, residents said that it feels like closures are becoming more frequent.

For instance, In June and July of 2019, the Glace Bay Health Care Facility was only open for a total of four days.

“There’s always questions because the ER continues to be closed. It continues to be closed. Nobody knows when it’s going to be open,” said McDougall.

Part of the challenge is informing a population about frequent but inconsistent closures.

The NSHA provides a list of ER closures on their website and alerts media organizations so they can share the information as well.

But McDougall said that sometimes just isn’t enough.

“It’s impossible to reach every single person and let them know. And then when you’re in a moment of peril, if you’re in a moment of emergency and I need to go, I need to get out and get help. Maybe if you don’t have access to the internet, it’s not going to be that simple to figure this out,” she said.

Losing faith in the system

According to health -care officials, the sense of frustration can make those needing care less likely to seek it — with Fraser saying every closure brings with it a chance that someone will be harmed.

McDougall agrees.

“This impacts that person who is on that gurney, but it’s also impacting our entire community because you start to lose faith in the health-care system.”

As the redevelopment of Cape Breton’s health-care facilities continues, the ability to staff the revamped facilities remains a challenge.

O’Neill said the NSHA is actively recruiting and that it’s an ongoing effort.

“It will continue to happen until we can get to the point where we have enough position resources to cover the site 24 hours a day,” she said.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.