When Justin Trudeau or Andrew Scheer approach a microphone and mention help for the “middle class,” Stephen Gordon cringes slightly.

Gordon, an economics professor at Université Laval, said the term — often peppered throughout speeches by politicians on the campaign trail — is essentially meaningless.

“There isn’t a standard definition so it can mean whatever people want,” he told Global News. “That’s kind of why politicians love it.”

The four main party leaders have mentioned the term middle class nearly 100 times on the campaign trail, and the Liberals reference the term 48 times in their 85-page platform.

The parties are also targeting voters with a slew of promises directed at helping the so-called middle class on everything from income tax cuts to free tuition to national pharmacare.

While economists might shudder when they hear talk about the elusive middle class, parties love to speak about this group because it appeals to the broadest section of voters.

“Everyone wants to believe they’re middle class,” Gordon said. “People don’t want to be low status, but you don’t want to be the one per cent or you’ll get things thrown at you.”

But whether or not you believe you are middle class is almost entirely dissociated from how much money you’re making, Melanee Thomas, a political science professor at the University of Calgary, said. Anyone making from $30,000 to almost $200,000 a year might consider themselves in the middle, she said.

“When a party leader talks about looking out for the middle class, people are generally self-reflective and say: ‘Oh, they’re looking out for me,’” she said.

“The concept becomes meaningless.”

So who, exactly, is in the middle class, and how much do you have to be earning to join this elusive group?

Get daily National news

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) says anyone making between 75 per cent and 200 per cent of the median national income is in the middle class. In Canada, that would be between just over $25,000 and $66,000, according to Statistics Canada. The median annual income in 2017 for a single person living in Canada was $33,000 and $92,700 for families.

Using the OECD classification, that would put roughly 60 per cent of Canadians in the middle-income bracket.

Gordon said politicians will often announce policies that help wealthier Canadians under the guise of helping the middle class.

“When that language is used to sell policies that basically benefit people much higher than those in medium-income distribution, that’s the part that bothers me,” he said.

But how far a median household income of $92,700 will take you can vary greatly depending on where you live in Canada.

- ‘A foreign policy based on short memory’: Carney continues push to diversify from the U.S.

- Carney says former prince Andrew should be removed from line to throne

- Canada and Japan sign partnership deal on defence, energy, trade

- LeBlanc says U.S. meeting on CUSMA and trade ‘constructive and substantive’

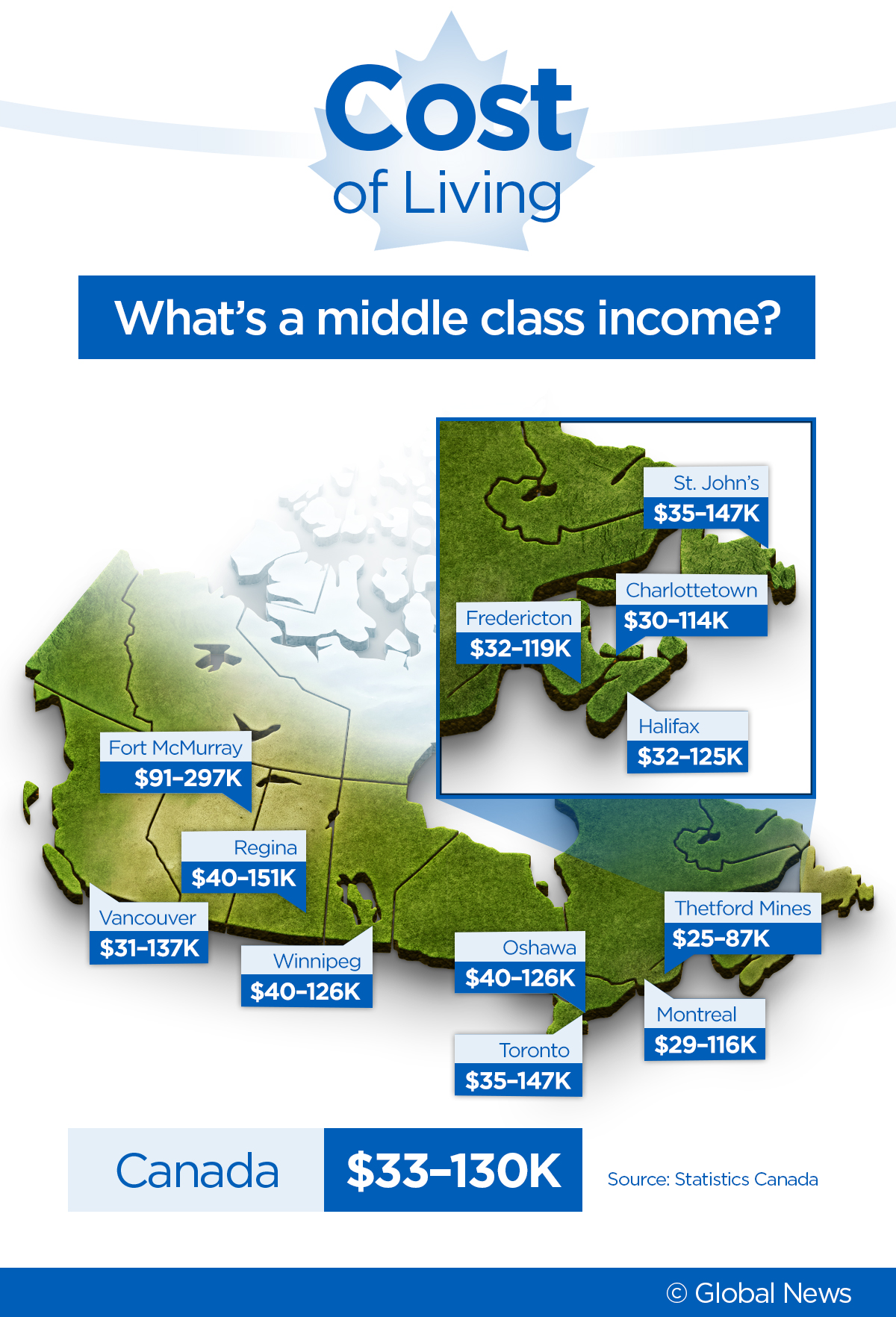

Data compiled by Statistics Canada for Global News based on the 2016 census found a wide disparity in what constitutes the middle class in various regions in Canada.

The StatCan data broke down Canadians into five equal groups based on reported income and then collected the middle three groups to represent the “middle class.” The numbers refer to all households, including individuals living alone, couples, couples with children and single parents with children.

REALITY CHECK: Does Trudeau deserve all the credit for Canada’s economic and job gains?

The data shows that households making between an average of $33,000 and $130,000 could be considered part of the middle class.

Shortly before the decline of Alberta’s oil and gas sector, Statistics Canada considered middle-class families in Fort McMurray to be making a range of $91,000 to $297,000, while households in Toronto made between $35,000 and $147,000.

“The income distribution differs dramatically across provinces,” said University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe. “If you’re earning $94,000 here in Alberta then you are right smack in the middle. But if you’re earning $94,000 in New Brunswick, you’re doing quite a bit better than average.”

READ MORE: Tired of high cellphone and internet bills? This election is full of promise(s)

Tombe said he finds the imprecise language around the middle class “frustrating” and that it is oftentimes just a political “buzzword.”

“This kind of conversation often misses the fact that individuals move quite a bit up and down the income distribution not just over their life but sometimes from one year to the next,” he said. “We can’t just target a particular set of people with a certain static level of income because then you’re missing the real underlying fluidity that exists.”

In Ottawa and Regina, median incomes weigh in at more than $80,000.

Recent Ipsos polling conducted exclusively on behalf of Global News looked at the voting intentions of the so-called sandwich generation — Canadians aged 35 to 54 who are caught between the demands of caring for at least one child and also caring for a parent.

The three polls conducted since the start of the election campaign — with a total sample of over 5,500 Canadians — found these voters had a greater likelihood of casting their ballot based on issues that directly affect their pocketbook, health and education.

READ MORE: Physicians decry omission of health care from federal leaders’ debate topics

The poll found the sandwich generation tends to lean Conservative, with 42 per cent of voters saying they would cast their vote for Scheer, nine points ahead of those who would vote Liberal at 33 per cent.

The Liberals have made a number of promises aimed at providing relief for the so-called middle class. They are pledging to make the first $15,000 for those earning under $147,000 tax-free and have also promised to increase the Canada Child Benefit by 15 per cent. The party is also pledging to make parental benefits tax-free and promising to create 250,000 new childcare spaces for before and after school.

REALITY CHECK: Trudeau claims Scheer is giving Canada’s wealthiest a $50,000 tax break

The Conservatives have promised their own “universal tax cut,” cutting the rate on taxable income under $47,630 from 15 to 13.75 per cent over three years. They’ve also promised to make Employment Insurance benefits for new parents tax-free, remove the GST from home heating costs and bring back the public transit and children’s fitness and arts tax credits ushered in under former prime minister Stephen Harper.

Tombe said the Liberal and Conservative income tax changes are quite similar, with the Grits’ changes focused more on the lower end of income distribution and the Tories’ on the higher end.

“The big differences between them are the Liberal one is more generous to single-earner families,” he said. “Whereas the Conservative one is better for dual-income families where both individuals are above the first bracket.”

READ MORE: A breakdown of false, inaccurate statements leaders made during the leaders’ debate

The New Democrats, meanwhile, have pledged $10 billion over the next four years to create 500,000 new childcare spaces in Canada, with the goal of offering free services for some parents, in addition to offering a national pharmacare program and free dental care for households earning under $70,000. They’ve promised to impose a one per cent wealth tax on the “super rich,” or those making more than $20 million.

The Green Party has promised free tuition for post-secondary students and to extend health-care coverage to include universal pharmacare plus dental care for low-income Canadians. They also want to increase corporate tax rates from 15 to 21 per cent and create a Federal Tax Commission to ensure the tax system is equitable.

Thomas from the University of Calgary said more constructive conversations should focus on what is actually required to maintain a decent standard of living.

“That would require a very different philosophical shift in how we talk about issues during an election campaign,” she said.

— With files from Erica Alini

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.