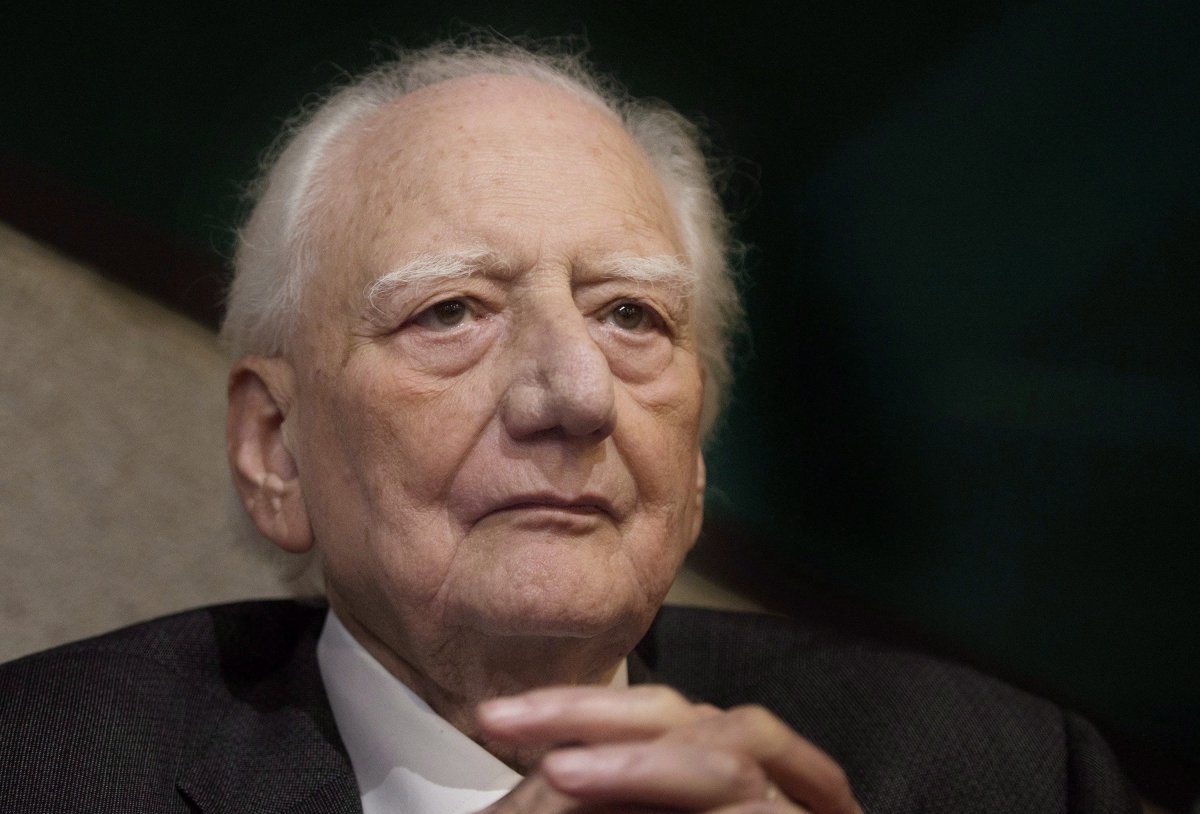

Roger Taillibert, the architect who designed Montreal’s 1976 Olympic Stadium and relentlessly defended it against its critics, has died at the age of 93.

The renowned French architect created hundreds of other buildings, including the Parc des Princes stadium and Deauville swimming pool in France and the Khalifa Stadium in Qatar.

But in Canada, he’s best known for the stadium that remains a defining feature of Montreal’s skyline. It remains the most visible legacy of the first Olympics on Canadian soil, but it has also been much maligned for ongoing maintenance issues and a surprise billion-dollar price tag that took the city 30 years to pay off.

Taillibert was born in France in 1926, and studied at the prestigious École du Louvre andÉcole nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts.

READ MORE: Comaneci, darling of ’76 Olympics, revisits Montreal

Taillibert’s success in France in the 1960s and early 1970s and his penchant for sweeping, grand designs attracted the attention of then-Montreal mayor Jean Drapeau, who asked him to design a stadium to house the 1976 Olympics and later the Montreal Expos baseball team.

Taillibert’s vision for the Olympic Stadium included a massive concrete dome with a retractable roof, held up by cables suspended from the world’s largest inclined tower, at 165 metres high.

Claude Phaneuf, the city of Montreal’s main engineer for the Olympic installations, said Taillibert’s genius and his technique of using pre-stressed concrete allowed him to design buildings with dramatic curves that surpassed what anyone else could do.

Get breaking National news

“He used circles, ellipses instead of straight lines. All his constructions were firsts of great genius, and those exist in the Olympic stadium,” said Phaneuf, who believes his friend never received the credit he deserves in Canada.

WATCH BELOW: Exhibit celebrates anniversary of Montreal Olympics

Taillibert, he said in a phone interview, was an exacting taskmaster who “didn’t tolerate mediocrity,” but he was also a loyal friend. The two spoke on the phone almost every day and spent time at Taillibert’s home north of Montreal, Phaneuf said.

“Sometimes we had discussions, we didn’t get along all the time, but I have to admit that (with) his superior knowledge and capacity, I had to eventually get behind his positions because he saw much further than I did,” he said.

Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante wrote on Twitter Thursday that Taillibert has left the city a great legacy.

“The Olympic Stadium is known in the four corners of the world and it gave us certain great moments in our history,” she said.

Taillibert remained proud of the design and continued to defend his creation over the years, despite criticism over its malfunctioning roof and an original price tag that ballooned to several times its original estimate.

Although the main stadium was built in time to host the Games, albeit barely, the tower and roof would not be completed until 1987. A later series of mishaps included a 55-tonne beam that came crashing down in 1991, a retractable roof that never worked as planned, and a 1998 roof tear that sent ice and snow crashing to the stadium floor, forcing the cancellation of two Rolling Stones concerts.

Taillibert, who once sued the city over his unpaid architect’s fees, always insisted that the stadium’s problems were due to mismanagement and cost-cutting rather than a design flaw.

“I’m very happy with the design,” he told The Canadian Press in 2016, citing its “beautiful” pool complex and use of ramps to aid mobility.

READ MORE: Desjardins to move into Montreal Olympic Stadium tower

Last year, at the age of 92, he was still consulting with experts to refine his original design for the roof, which he insisted would be the best and most cost-effective solution to replace the current one, which is torn in thousands of places.

Taillibert’s career as an architect spanned decades, and his legacy includes buildings across Europe as well as in Canada, Jordan and Qatar.

In recent years, Taillibert divided his time between Paris and his home in St-Sauveur in Quebec’s Laurentians region, where according to Phaneuf he continued to swim, cycle, and take an active interest in Quebec politics until his death.

In addition to being an architect, Taillibert was also an accomplished painter.

One of his final public appearances was at the opening of an exhibit of his drawings, paintings and sketches that ran last summer in Repentigny, north of Montreal.

Comments