Through the latter half of the 1970s, some areas of the music community were having a Marshall McLuhan-esque existential crisis thanks to the rise of synthesizers and the adoption of new studio technology.

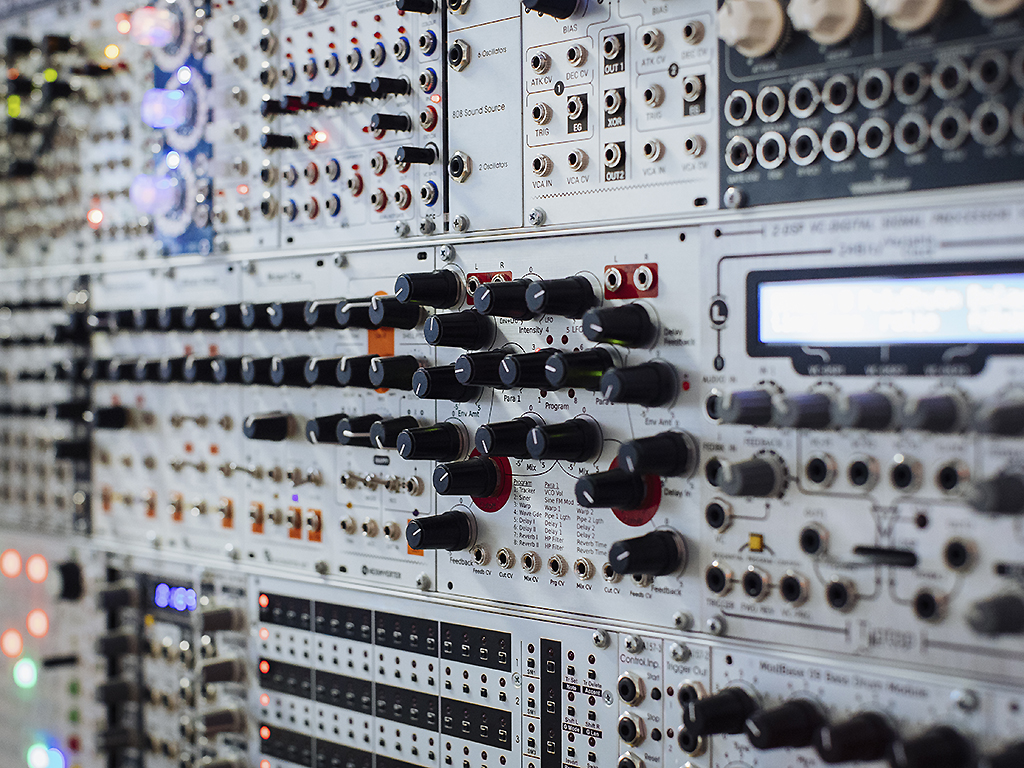

The new machines, many of which could perform tricks that no human could ever duplicate manually, were driving music into new territory at a fearsome speed. Was humanity being sapped from music? Were humans going to lose control of music? And were these new artificial sounds, methods of recording, and programmed robotic performances actually music in the first place?

And it wasn’t just music. Technological change was sweeping through photography, movies, radio and television. It all seemed both very exciting and very overwhelming.

READ MORE: The Cult’s Ian Astbury talks Indigenous influence and the evolution of the band

In late 1978, Trevor Horn, an English session player and producer, sat down with keyboardist Geoff Downes and songwriter Bruce Woolley to write a new wave-ish song about music, mass media, and the way the public was being force-fed it all. I wouldn’t be surprised if they had Network‘s Howard Beale on their mind.

Horn had recently read a 1960 short story called The Sound-Sweep by British writer J.G. Ballard that told the story of a nonverbal boy with the job of vacuuming up all the stray music in the world. He meets a destitute opera singer living in an abandoned recording studio whose career had been ruined thanks to something called “ultrasonic music.” All of humanity’s music had been displaced and replaced by this new technology.

Kraftwerk was another inspiration. Their “man-machine” approach to music had Horn thinking about the possibilities of record labels having vast banks of computers in subterranean vaults that would in the near future be tasked with writing and performing all of humankind’s music.

The Buggles were envisioned as part of that, a “robot Beatles” that would never be seen — or at the very least, never play live. (Fun fact: The original name of the band was The Bugs, as in “studio insects.”)

As the new song came together, Horn, Downs, and Woolley jammed on concepts of modern technology clashing with nostalgia, a fear of the future combined with a sense of loss for the past. It took three months to write and record their new song using up a budget of £60,000 (about C$100,000 then, or about C$380,000 today). In keeping with the theme of the song, many of the instrumental parts were generated by synthesizers. (Another fun fact: The original demo was sung by a woman named Tina Charles.)

Woolley released the song first with his band The Camera Club, a group that featured a young Thomas Dolby on keyboards.

READ MORE: Sum 41 releases new song, ‘A Death in the Family’

That was fine, but the version everyone knows is by The Buggles, which featured Woolley, Horn, and Downes. It was released on Sept. 7, 1979, and was an immediate hit, reaching the number one spot on singles charts in 16 different countries. (In Canada, it only managed to climb to number six while in the U.S., the song barely scraped into the Top 40.)

In 1981, the song was completely repurposed for a new venture called MTV. What began as a tale about music-making machines displacing an opera star from her spot on the radio became a rallying cry for those promoting this new thing called a “music video.” No wonder this was chosen to be the first clip played by MTV when it debuted at precisely 12:01 a.m. ET on Aug. 1, 1981.

In those opening minutes, VJ Mark Goodman promised that we’d “never look at music the same way again.”

“The best of TV combined with the best of radio,” he said. “We’ll be doing for TV what FM did for radio.”

Radio didn’t much fear the video star at first because many cable systems didn’t see the value of carrying a 24-hour music video channel.

But then a strange thing began to happen. Cities that did have access to MTV saw dramatic spikes in the sales of records by artists whose clips were played on the channel. Why would an unknown band like, say, Duran Duran, start selling records by the ton in Oklahoma City? Sales stats like that combined with the channel’s aggressive “I want my MTV” campaign resulted in a massive uptick in public demand. Soon, all cable companies were offering it.

READ MORE: Fans praise Keanu Reeves for how he takes photos with women

Through the ’80s and ’90s, radio and music video channels lived side by side in a sometimes competitive, sometimes symbiotic state. Basic cable channels got into the act, too, carving out after school and late-night shows featuring music videos. Remember CBC’s Good Rockin’ Tonight?

Record labels supplied the music videos gratis to these channels and shows because they knew airing them would goose record sales. Artists knew that production costs came out of their future royalties, but it all became part of doing business. You had to spend money to make money.

While we still had radio stars — that is, performers who had hit records on FM and (for a while longer, anyway) AM radio — MTV, MuchMusic, The Box, and other channels and outlets created video stars, telegenic performers whose fame was driven by not only how they sounded, but also by how they looked. The list is near endless: Michael Jackson, Madonna, Cyndi Lauper, Duran Duran, Prince, Bon Jovi, Guns N’ Roses, Nirvana.

Meanwhile, the VJs — the other stars of video — became famous in their own way. It was all pretty glamorous. It was only going to be a matter of time before visual music killed off the old DJs on the wireless.

A funny thing happened, though. Radio refused to roll over and die. While it had to share space with video channels, it learned to adapt. It continued to adapt in the era of the internet, through the rise of satellite radio, and now through the age of streaming. With more than 88 per cent of the Canadian population tuning in to radio every week — a number that’s even higher in the U.S., the U.K., Australia and a number of countries throughout Europe — radio remains popular, powerful and profitable. Ask any artist and they will still tell you that the fastest and most efficient way to get their music out to a mass audience is radio.

And those video stars? They’ve all moved to YouTube. The novelty of waiting for your favourite music video to come up on Much or MTV disappeared long ago, forcing programmers to cancel (or highly marginalize) music video-based programming in favour of reality and lifestyle shows. And whither all those VJs? Moved on to other things, including satellite radio (Mark Goodman, Martha Quinn, Nina Blackwood, Downtown Julie Brown, J.J. Jackson before he died in 2004), podcasts (Adam Curry), and even good ol’ terrestrial radio (Carson Daly, Chris Booker, Matt Pinfield).

Turns out that no matter how you define that Buggles threat in 1979, video did not kill the radio star. Radio is still just fine, thank you.

And one more thing: On Feb. 27, 2000, MTV aired its one-millionth video. What did they pick to make that momentous occasion? The Buggles’ Video Killed the Radio Star, of course.

—

Alan Cross is a broadcaster with 102.1 the Edge and Q107, and a commentator for Global News.

Subscribe to Alan’s Ongoing History of New Music Podcast now on Apple Podcast or Google Play

Comments