For years, residents in some of Canada’s largest industrial cities have wondered whether toxins from petrochemical plants and other manufacturers are making them sick.

A new peer-reviewed study has found “strikingly high” rates of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in Canadian border towns, including Sarnia, Ont., a city whose manufacturing sector is referred to as Canada’s Chemical Valley.

The study reviewed 18,085 Canadian cases of AML between 1992 and 2010. It found hot spots for this type of leukemia in several Canadian cities, including Hamilton, Thunder Bay, Sault Ste. Marie, Sarnia and St. Catharines.

Sarnia was at the top of the list.

READ MORE: Toxic Secret — Are industrial spills in Canada’s ‘Chemical Valley’ making people sick?

Local residents in Sarnia have long been raising public health concerns about the impacts of industrial pollution. The city is surrounded by 57 companies which are registered to emit pollutants, including oil refineries and other chemical plants on either side of the U.S.-Canada border.

Overall, Sarnia had about 1.5 times more cases of AML than the national average, but the frequency of cases was even higher in the north side of the city and neighbouring Village of Point Edward.

“The incidence of AML (in this area) … was a striking 106.81 cases per million per year, which is more than three times the Canadian average,” said the paper, published on Feb. 27, 2019, in the journal, Cancer.

BELOW: The N7V postal code region in northern Sarnia has reported AML rates that are three times the national average.

The authors found this area had the highest incidence in the country, while the other significant hot spots were also in industrial regions of Ontario.

The province of Prince Edward Island was also identified as a hot spot.

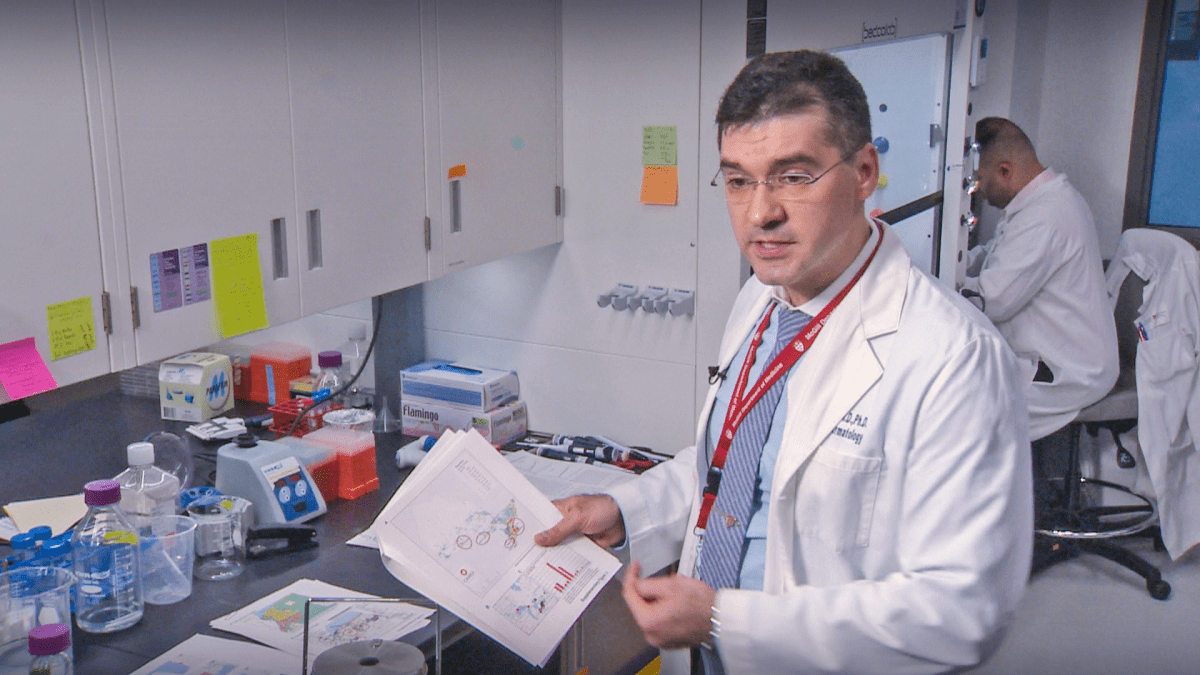

The paper was produced by a team of researchers led by Ivan Litvinov, a Montreal dermatologist, out of the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre.

“There’s quite a lot of people who are suffering. And so that means we’ve got to get our resources out there,” Litvinov said. “We need to make sure that we have the education, the support services and our abilities to treat those patients.”

The scientific study noted that benzene, a known carcinogen, is also a key risk factor in the development of AML. Benzene is one of the toxins released into the air by petrochemical plants.

Get weekly health news

The study found cities with the highest levels of benzene in the air, such as Sarnia, were also the cities with the highest levels of AML.

“Collectively, these findings support the possible link between benzene exposure and leukemogenesis and highlight its significance as a major risk factor for AML in the Canadian population,” the study said.

While Ontario has the most stringent limits on benzene levels in Canada, this limit is consistently exceeded in Sarnia.

In fact, recent federal air monitoring data released to Global News by Environment and Climate Change Canada shows that benzene levels in Aamjiwnaang First Nation, on the south side of Sarnia, were three times the regulated annual limit in 2017.

In July 2017, five companies that said they couldn’t meet Ontario’s stringent benzene standard were approved instead for an alternative process, called a “technical standard.” Under a technical standard, companies are not breaking the law if they don’t meet the benzene standard — but are required to make progressive technical modifications, including greater leak detection and repair.

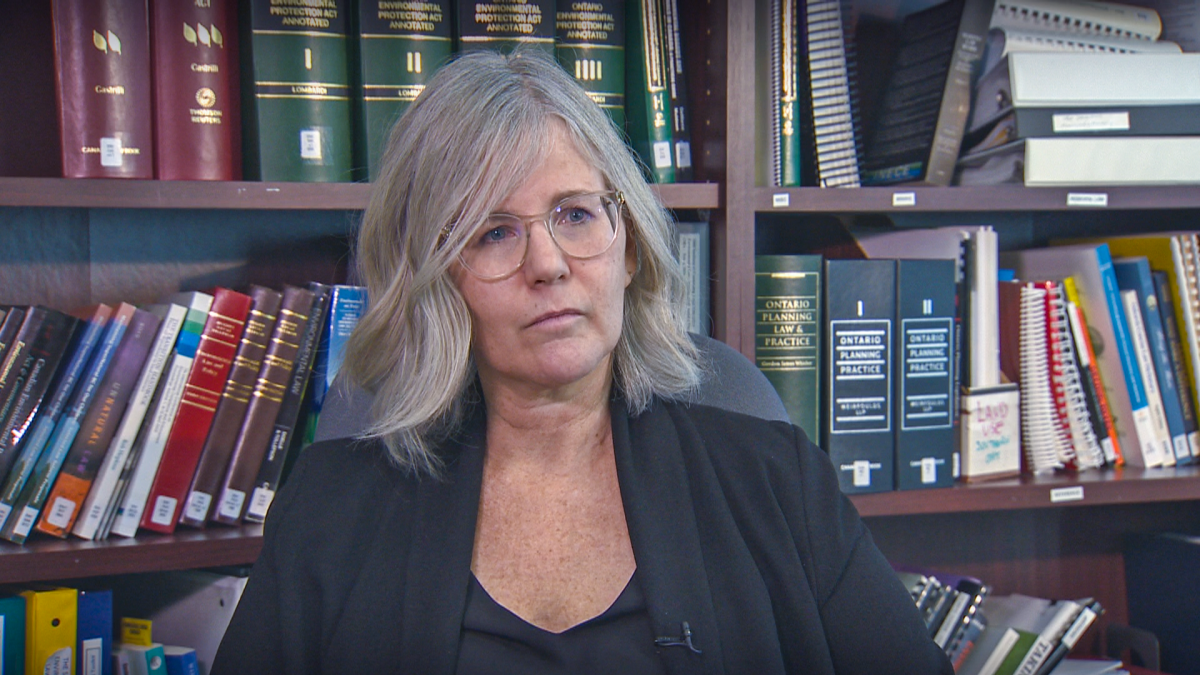

Elaine MacDonald, a program director at Ecojustice, a non-profit environmental law firm, said that the public should be “angry” that the government has let them down.

“People want to think that they’re being protected, that the government is properly regulating industrial emissions and what this study is showing is that they’re not,” MacDonald, an environmental engineer, told Global News in an interview.

Wilson and Dorothy Plain, who live in Aamjiwnaang First Nation, lost their 13-year-old son, Jeremy, to AML in 2006.

Dorothy Plain previously told Global News in 2017 that she doesn’t think there is any safe amount of benzene that can be released by chemical plants.

“I always wondered in the back of my mind, knowing where we live and what’s around here, ’Well, does that have something to do with it?’” said Wilson Plain Jr., of his son’s death.

READ MORE: ‘It’s a disgrace’ — A year after Ontario promised change, toxic emissions still spilling into Sarnia

The federal environment department noted that it published draft regulations to control toxic pollution from the petroleum sector — including benzene, which is a volatile organic compound — in May 2017. Two years later, Environment and Climate Change Canada says it “remains committed to publishing final regulations.”

Successive federal and provincial governments have been consulting with industry and studying new air quality standards and regulations for more than a decade. Both levels of government have introduced some new regulations to reduce pollution from vehicles and industrial plants.

But the existing regulations don’t fully cover a number of toxic substances released from petrochemical plants that are linked to health problems such as asthma or cancer.

WATCH BELOW: One year after Canada’s toxic secret exposed

The International Agency for Research on Cancer — a division of the World Health Organization — classifies benzene as “carcinogenic to humans” based on evidence that it causes AML. The agency also says that benzene has been linked to other forms of cancer.

“We were surprised to see that, actually, the areas that were scoring very high on benzene exposure were also the towns that were highlighted by the incidence of AML,” Litvinov said. “That just seems to further corroborate the data from the International Agency for Research on Cancer. … This is something that our public and regulatory agencies should probably know about.”

The Ontario government is moving ahead with a health study to get more information about how industrial pollution may affect the population. This came in response to an investigation by Global News in 2017 about what was happening in Sarnia.

“We’ve committed over $2 million to make sure that the study gets done,” Ontario Environment Minister Rod Phillips said in an interview. “We also brought the federal government onside. They’re also going to be contributing to the study, as is the community.”

Global News and the National Observer reached out to a local industry group representing petrochemical companies in the region, the Sarnia-Lambton Environmental Association.

Vince Gagner, a spokesman for the group, declined an on-camera interview but did comment in an email that the new research could “play a role” in the ongoing health study, prompted by the Global News 2017 investigation.

Previously, a provincial government health organization, Cancer Care Ontario, studied incidence of 24 different types of cancer, including leukemia, over a shorter period from 2004 to 2008, but didn’t identify what Litvinov’s study uncovered. The provincial research also considered a person’s age as part of its study, but it didn’t specifically look at AML.

“Their study is important in that it’s among the first studies to report on the burden of AML across Canada,” said Todd Norwood, a staff scientist at the provincial organization, in a phone interview.

WATCH BELOW: A troubling trend of leaks and spills in the Sarnia area

Norwood said that it would be important for researchers to continue building on the latest study, including additional comparisons about age and gender, to identify larger trends and patterns.

Litvinov added that provincial officials have already been in touch to exchange information and learn more about his team’s research.

The study authors also said more research was needed to review risk factors, which could include occupational risks or lifestyle factors such as obesity or smoking.

Litvinov also said that hospitals would have more data and information that could be useful to identify the nature of the problem.

“Once we have all this data, we would have a much fuller picture to come to regulating bodies to say, ‘We really think that we’ve seen a signal. The signal is true. It’s supported with molecular and clinical data. Now let’s do something about it.’”

megan.robinson@globalnews.ca

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.