The conventional wisdom about Canada’s premier account for retirement savings is clear: do not take money out of your registered retirement savings plan (RRSP) until your golden years.

The advice makes sense for most people. Withdrawing from your RRSP usually means you’re pillaging your retirement fund and losing the tax advantage that comes with leaving the funds untouched until the end of your working life.

Richard Shillington, though, has a different take. Many Canadians “would be well advised to cash out any RRSPs around age 65,” the Ottawa-based statistician wrote in a recent report for the Institute for Research on Public Policy.

READ MORE: When saving into an RRSP instead of a TFSA could cost you dearly

Shillington, who sits on the Council on Aging of Ottawa’s expert panel on income security, is shining a light on an issue that’s become well known among some financial planners but hasn’t fully made its way into the financial-advice mainstream: using RRSPs can result in significant clawbacks of government benefits for some seniors.

The retirees Shillington is talking about are those receiving the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS), among other income-tested benefits and tax credits. And there are many more such seniors than people realize, he notes.

WATCH: Why deferring withdrawing from your RRSP may be a bad idea

“Some walk around thinking that if you receive the GIS, you have no savings,” he told Global News via telephone. “It’s not true.”

Statistics show just under one-third of seniors in Canada receive the benefit, he added.

When RRSPs are great — and when they are not

With an RRSP, income taxes are deferred. You don’t pay tax when you put money into the account, only when you withdraw. (That’s why you generally get a tax refund when you make a lump-sum deposit into an RRSP. You have essentially overpaid your income taxes: the taxman is returning the taxes you paid on the money you used for the contribution.)

Canadians usually convert their RRSPs into so-called registered retirement income funds (RRIFs) when they stop working (and must do so by the year they turn 71). Then they start taking money out, gradually, for use throughout retirement. Withdrawals are taxed at a rate based on their overall annual income.

READ MORE: How much do you really need for retirement? We did the math

This works well for many Canadians. People often need less income in retirement when, say, the mortgage is paid off and the kids have moved out. A lower income comes with a lower tax rate, so the taxes they pay on their RRIF withdrawals are lower than the taxes they didn’t pay on their RRSP contributions. In general, the higher one’s pre-retirement income tax rate is compared to their post-retirement tax rate, the greater the advantage in using RRSPs/RRIFs.

It’s a pretty sweet deal — but that math doesn’t work for everyone.

READ MORE: Save or pay down the mortgage? Rising interest rates are changing the math

If your expenses — and the level of income you need to cover them — aren’t going to change much after retirement, there won’t be much difference between your pre- and post-retirement income tax rate. The investments inside your RRSP still get to grow tax-free, but that would also be true if you had put the money into a Tax-Free Savings Account (TFSA).

Government benefits, though, can tip the balance strongly in favour of TFSAs for some seniors, Shillington notes.

The key difference is that money taken out of an RRSP or RRIF counts as income for tax purposes, while TFSA withdrawals do not. This means that RRSP/RRIF money can put seniors in a higher income bracket that results in a partial or full clawback of government benefits.

WATCH: Weighing the costs and benefits of reverse mortgages

The consequences are especially serious for lower-income seniors, Shillington shows. These retirees are usually eligible for the GIS, a supplementary, non-taxable amount they receive along with their Old Age Security (OAS) pension. But GIS benefits are rapidly scaled back as income rises.

Generally speaking, seniors lose roughly 50 cents in GIS benefits for every $1 of income, Shillington notes in the report.

For example, if a retiree withdrew $1,000 from their RRSP, depending on their income, they would stand to lose $500 in GIS benefits — and still be taxed on their $1,000 withdrawal, Shillington told Global News. By contrast, $1,000 out of a TFSA would have no impact on their GIS amount.

Seniors may also face benefit clawbacks on other income-tested benefits, such as drug and rent subsidies, he noted.

READ MORE: Nest-egg inequality explains why women need to save more than men

That’s why Shillington argues lower-income seniors should consider emptying out their RRSPs around age 65 and transferring the funds to a TFSA.

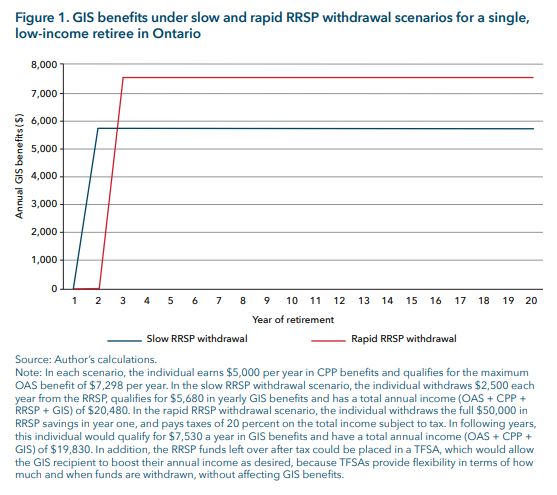

Imagine, for example, a single senior whose annual income consists of OAS, GIS and $5,000 from the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and who has $50,000 in an RRSP. If this individual gradually tapped the RRSP/RRIF by withdrawing $2,500 annually for 20 years of retirement, they would get $5,680 a year in GIS benefits. Including CPP and OAS, their overall annual income would be $20,480.

If the senior emptied their RRSP in the first year and moved the money to a TFSA, they would be ineligible for the GIS benefit for that year but receive $7,530 in GIS benefits in every subsequent year. After paying income tax on the $50,000 withdrawal from the RRSP, the senior would be left with $40,000 in a TFSA, enough for annual withdrawals of $2,000 over a 20-year period. This senior’s overall annual income after year one would be $21,830.

WATCH: Should you pay down the mortgage or save for retirement?

After 10 years, TFSAs are still misunderstood

TFSAs were created, in good part, to help lower-income seniors, Shillington notes in the report. He quotes former finance minister Jim Flaherty, whose 2008 budget speech read:

“A TFSA will provide greater savings incentives for low- and modest-income individuals because neither the income earned in a TFSA nor withdrawals from it will affect eligibility for federal income-tested benefits and credits.”

A decade after the fact, though, just 36 per cent of Canadians without a work pension plan have opened a TFSA, Shillington points out.

In part, this may be due to the fact that Canadians retiring today only had RRSPs at their disposal for most of their working lives.

WATCH: Why women need to save more for retirement

It doesn’t help that Canadians with modest income have limited access to financial advice, Shillington told Global News. And when they do seek advice, they often get cookie-cutter answers that are tailored for people with middle class incomes.

“I blame the banks,” Shillington told Global News.

“Financial institutions understandably design their advice for a population that has money … and they’re not doing a very good job of identifying the people who are going to be on GIS,” he said. “But that is not a marginal group.”

READ MORE: Here’s what taxes can do to your savings if you’re not careful

Financial planner Jason Heath says confusion about TFSAs is rampant across the income spectrum.

“Some middle-income earners, who would probably benefit from RRSP contributions, opt for TFSAs to avoid the evil ‘tax hit’ on RRSP withdrawals but give up great tax deductions and tax deferral in the meantime,” he told Global News via email.

“Other low-income earners who should probably pay down debt or contribute to a TFSA, instead make RRSP contributions because RRSPs are ‘for retirement,'” he added.

And many Canadians across the board use TFSAs as savings accounts instead of investing their money, giving up the chance of truly benefitting from tax-free growth, he said.

Heath agrees that low-income seniors can benefit from drawing down their RRSPs in their 60s, especially if they are conservative investors and have a long life expectancy.

A good strategy for them may also be to use their RRSP savings early in their retirement and defer CPP and OAS benefits until age 70, as these increase by 8.4 per cent and 7.2 per cent, respectively (plus inflation), with each year of deferral, Heath added.

However, delaying OAS also means postponing receipt of the GIS, for which there is no increase upon deferral, Heath and Shillington both noted.

Still, the overarching point is the same. As Heath put it: “Strategic early RRSP withdrawals and the use of TFSAs for retirement savings instead can help those who need it most to maximize their government pensions.”

Comments