An Ethiopian Airlines passenger jet en route to Nairobi crashed minutes after taking off Sunday morning, killing all 157 people on board.

The plane was a Boeing 737 MAX 8, the exact same model that was involved in a fatal crash in Indonesia five months ago. That crash killed 189 people.

Two crashes involving that specific, newer model jetliner in less than half a year have ignited fresh safety concerns about a company that’s long been seen as the most reliable maker of passenger aircraft.

WATCH: Retired flight safety analyst says recent incidents involving Boeing 737 may be due to differences between models

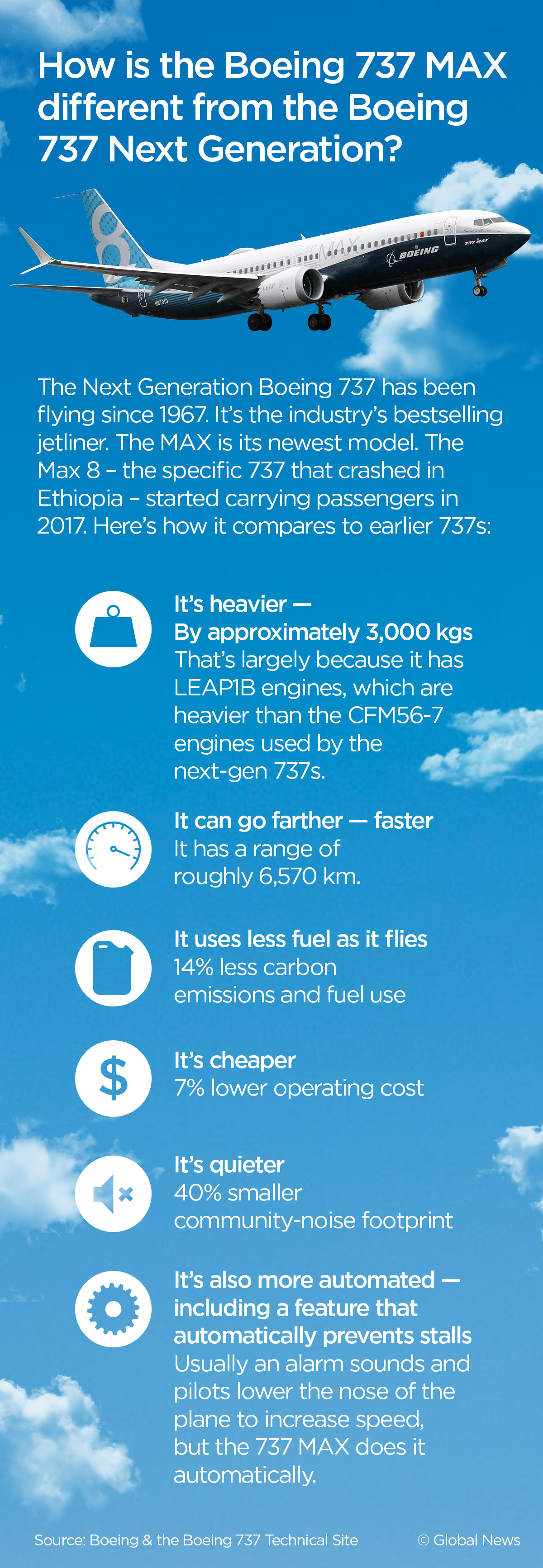

So how, exactly, does the newer Boeing 737 MAX fleet compare with Boeing 737 Next Generation, the previous series in a line that’s carried passengers since 1967?

“It’s very similar, just more technology,” said aviation expert Jock Williams. Basically, he says, it’s “better toys in the plane.”

That’s not unique to Boeing, Williams explains. Planes have been advancing in tandem with technology. They’re now built using fibreglass instead of aluminum, and autopilot, which didn’t work reliably when Williams was a pilot, is now routine.

The Boeing 737 MAX 8 is faster and more fuel-efficient

In building the MAX line, Boeing made a few modifications so that its new jets could fly faster and further. Per Boeing, the MAX 8 has a range of roughly 6,570 kilometres. It’s a heavier plane by roughly 3,000 kilograms, according to the Boeing 737 Technical Site, hosted by a U.K. pilot with a degree in physics.

That’s due in large part to its engines, which are LEAP-1B models instead of the CFM56-7 engines installed in the 737 Next Generations. But while the MAX 8s are heavier, they are ultimately more efficient, using less fuel and producing 14 per cent fewer carbon emissions. That’s a savings for airlines that use them, as operating costs are seven per cent lower with Boeing MAX models than they are with 737 Next Generation models.

WATCH: China orders its airlines to ground Boeing 737 MAX 8 jets

“The MAX 8 is designed to go fast and far and is, I think, a very successful design,” Williams said. “I think we’ll be flying MAX 8s 25 to 30 years from now.”

That is, he cautions, if people don’t “jump to conclusions” that the model is to blame for the crash.

The “anti-stall” system people are questioning in the wake of the crash

From a pilot’s perspective, the Boeing 737 MAX line is likely “85 per cent the very same to fly” as a Boeing 737 Next Generation. One of the big differences that’s being scrutinized in the wake of the second fatal crash is the MAX 8’s automated anti-stall system, also known as the plane’s manoeuvring characteristics augmentation system, or MCAS.

An airplane is at risk of stalling when there isn’t enough wind speed over the wing. Typically, an alarm of some sort will sound, alerting the pilots, who will lower the nose of the plane in order to increase speed and come out of the stall.

Air France Flight 447, which crashed into the ocean while flying from Rio de Janeiro to Paris, killing all 228 people on board, was partly the result of a stall. A final report into the 2009 crash found the pilots were not able to recover from the stall, with one pilot tilting the nose of the plane up instead of down.

The Boeing 737 MAX 8’s MCAS essentially automates this feature in order to compensate for its new engine, which had to be moved forward, changing the plane’s centre of gravity and increasing the risk of a stall.

“The designers were worried after the test pilots tested the aircraft. They found that the airplane had some instability problems,” said Ross Aimer, a former pilot and CEO of Aero Consulting Experts.

Enter MCAS.

WATCH: Warning on Boeing 737 MAX planes after Indonesia crash

Williams explains that in most plane models, the pilot is trained to push the yoke — the steering column — forward while applying full throttle to lower the nose and build the plane’s speed up again.

The Boeing 737 MAX 8 does it automatically.

“So the pilot says, ‘Holy jeez, this feels a lot different from anything I’ve ever felt before,’” William said. “Then he does something else and, once again, the plane surprises him with its response.”

Were pilots trained on the new “anti-stall” system?

It’s too soon to say exactly what caused the Ethiopian Airlines flight to crash on Sunday. Investigators recovered the plane’s partially damaged black box on Monday. A growing number of companies are grounding the Boeing 737 MAX 8 while they await answers, although Federal Transport Minister Marc Garneau says Canada will not order its airlines to ground their MAX 8s.

However, Aimer says Boeing “did not disclose this fairly important addition to the operators.” Indeed, the family of a victim in the Indonesia crash in October filed a lawsuit saying the company had effectively “blinded” its pilots.

WATCH: Global News coverage of the Ethiopian Airlines plane crash

The lawsuit claims the pilots spent the bulk of the minutes-long flight fighting the anti-stall system, which kept lowering the nose of the plane as a result of allegedly incorrect data from the sensors in the automatic system, which they didn’t know existed.

“Pilots always want to know what exactly ticks in their airplane,” Aimer said. “And they had no idea about this.”

Aimer adds that Boeing is updating the software to make sure the sensors work correctly, although the company didn’t address that in its statement after Sunday’s crash.

“Boeing is deeply saddened to learn of the passing of the passengers and crew on Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302,” reads the three-line statement. A Boeing technical team will go to the crash site to provide support.

—With files from Andrew Russell

_2_848x480_1455788611861.jpg?w=1200&quality=70&strip=all)

Comments