Imagine if we could predict whether someone was going to commit a violent crime years before they ever picked up a weapon.

The notion might sound like a plot line from a futuristic sci-fi thriller, such as Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report, where police can peer into the future. But our ability to predict a person’s propensity for violence is fast becoming a reality.

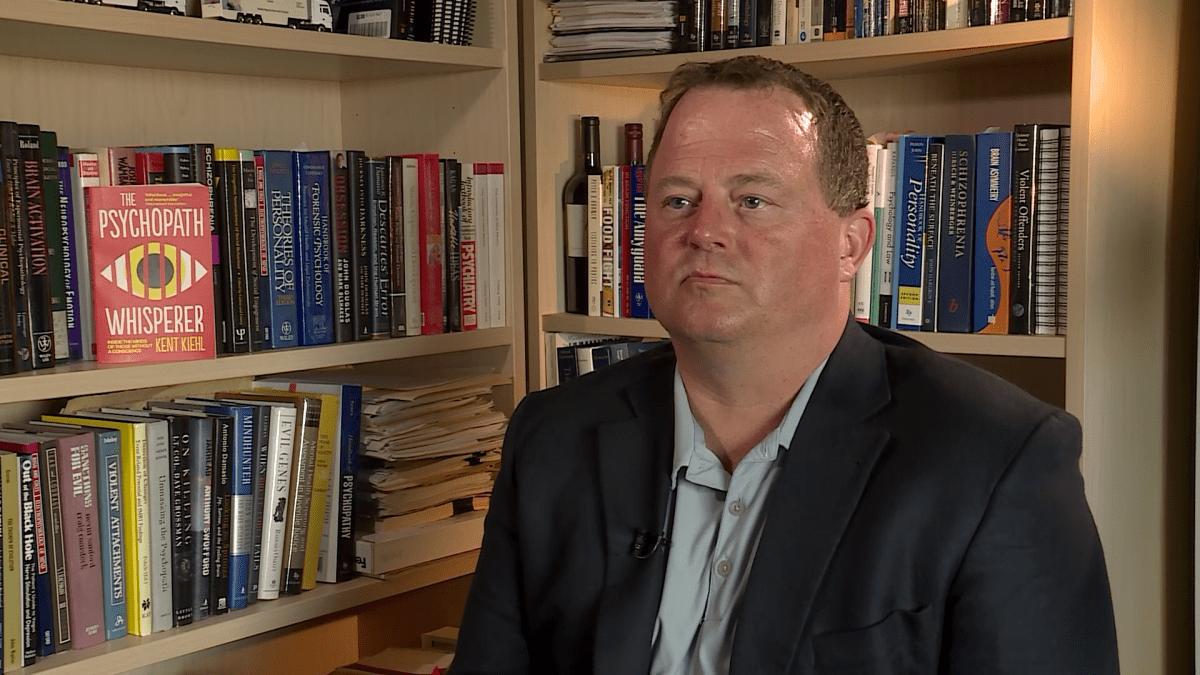

“The real goal is prevention,” says neuroscientist Kent Kiehl. “It’s to help identify children at risk for these conditions and to steer them away from it before they ever enter the criminal justice system.”

Kiehl runs the non-profit Mind Research Network in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and is one of the world’s leading experts in psychopathy — a personality disorder characterized by impaired empathy and remorse that affects around 25 per cent of the North American prison population.

“We’ve now got techniques that can show us how their brains are different. And it’s a fairly robust difference,” Kiehl explains.

Kiehl is a former graduate student at the University of British Columbia, where he studied under famed Canadian psychologist Robert Hare and was among the first to identify psychopaths by imaging the brains of prisoners in Abbotsford, B.C.

Get daily National news

“Building upon those original studies at UBC, we’ve been able now — in sample sizes 100 times bigger — to show exactly what we think is wrong or different about the psychopathic brain. People who have these traits — lack of empathy, guilt and remorse — they’re very glib, superficial. And they’ve been this way from the very beginning, from a very early age.”

Over the past two decades, Kiehl and his colleagues have conducted brain scans on more than 5,000 inmates in Canada and the United States, the largest sample of its kind. The scans revealed that psychopaths’ brains are visibly different: The orbitofrontal cortex (behind the eyes) and the amygdala (deep inside the brain), which are responsible for producing feelings of guilt, remorse and fear, are dysfunctional in psychopaths.

“It’s become almost diagnostic,” he says. “These areas of the brain that are essential for processing normal emotions and having a normal emotionally life, it’s like they have a weaker muscle mass; there’s less tissue there, there’s less volume. They’re just not able to do the heavy-lifting that the rest of us take for granted.”

WATCH: Canadian criminologist helps create algorithm to catch serial killers

Unlike in Hollywood movies, where the word ‘psychopath’ is almost always synonymous with a murderous madman, most real-life psychopaths are not killers. In fact, Kiehl says roughly one in 150 adult males is a psychopath, meaning many of us likely know someone who fits the profile.

“They’re very good at faking and conforming or blending in,” explains Michael Artnfield, a criminologist at Western University. “They’re very good chameleons. And that duplicity is part of what makes them so dangerous.”

As shown in this Global News Explainer video, most serial killers also fit the definition of a psychopath, which is often combined with a traumatic childhood and pathological sexual fetishes. “When you get multiple different things going on, you can get a really dangerous person,” Kiehl explains.

The science of psychopathy is now shifting from identification to prevention. A therapy program for young male psychopaths was able to reduce the rates of re-offending for violent crimes by up to 50 per cent. “So that means that a boy who receives this treatment is 50 per cent less likely than a peer who doesn’t receive this treatment to re-offend violently,” Kiehl says. “That is amazing progress in a field that used to be synonymous with re-offending. Almost all psychopaths will commit a new crime within 10 years.

“There are very few attempts to treat this condition. And that’s what I hope changes in the future.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.