France’s yellow vest protesters, called “les gilets jaunes,” are protesting the rising living costs associated with the country’s carbon tax and, more specifically, the dramatic increase in gasoline and diesel prices.

The protesters number in the thousands, and they torched cars, looted stores and tagged the iconic Arc de Triomphe with graffiti. One woman died in the protests.

French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe granted a temporary victory to the people Tuesday, stalling another planned gas price increase slated to take place in January. Now, the fuel price increase of approximately €0.03 per litre of gas and €0.06 per litre of diesel will come into effect six months later.

France’s plight illustrates a conundrum: how do political leaders introduce policies that will do long-term good for the environment without inflicting extra costs on voters that may damage their chances of re-election?

It is a question facing leaders across the world as delegates hold talks in the Polish city of Katowice this week and try to produce a rule book to flesh out details of the 2015 Paris Agreement on fighting climate change.

The protests have already inspired copycat incidents elsewhere — Belgian police used water cannons on protesters wearing yellow vests last week.

READ MORE: Why France’s ‘yellow vest’ protesters are rioting in Paris and across the country

Asked if the government was worried about similar protests in Canada over the introduction of carbon taxes and other climate plans, Environment Minister Catherine McKenna dismissed the idea.

“Our approach has always been how do you have smart policies that reduce emissions, but in a way that makes life affordable for Canadians,” she said Tuesday.

WATCH: Flames flicker on streets in French city as France students continue to protest Macron reforms

“I think Canadians understand the costs of climate change — they’re paying the cost,” she said.

Get breaking National news

“I had to call a rancher whose ranch literally burned down. I met with paramedics who had to rescue people from flooding in Toronto. People have died of extreme heat; we’re paying the cost right now of our inaction over decades.”

READ MORE: Confused about carbon taxes and rebates? Here’s what you need to know

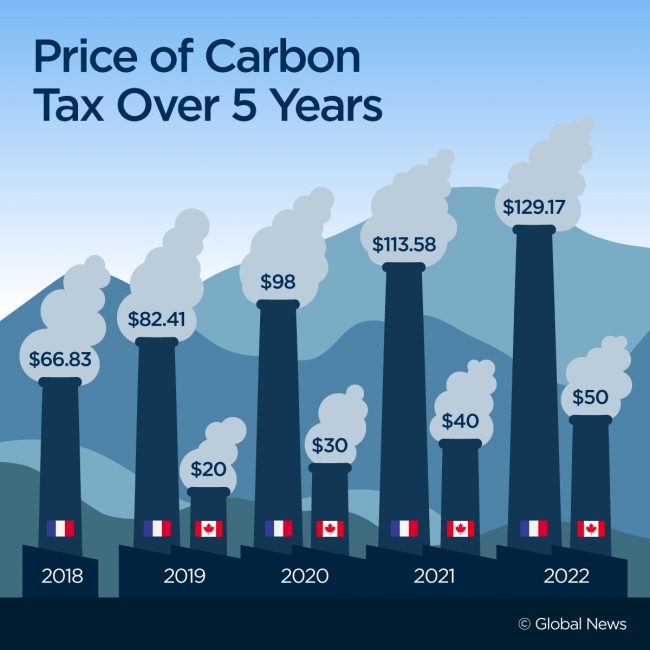

Canada’s planned carbon tax, introduced in October and expected to take effect in January, would see a tax of $20 per tonne of emissions — and that would rise by $10 a year until it reaches $50 per tonne.

The tax will be on industry and companies, but it’s expected the cost will be passed onto consumers via higher electricity and heating bills along with added driving costs from the gas surcharge.

In France, the carbon tax in 2018 was €44.6 ($66.83) per tonne and will rise to €86.20 ($129.17) in 2022.

- Canadians have billions in uncashed cheques, rebates. Are you one of them?

- Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump heritage site enjoys boost after shout out on ‘The Pitt’

- What is Nipah virus? What to know about the disease as India faces outbreak

- Income and wealth gaps increased in 3rd quarter of 2025: StatCan

| France | Canada | |

| 2018 | €44.6 ($66.83) | – |

| 2019 | €55 ($82.41) | $20 |

| 2020 | €65.40 ($98) | $30 |

| 2021 | €75.80 ($113.58) | $40 |

| 2022 | €86.20 ($129.17) | $50 |

The higher carbon tax, along with a tax increase on diesel, was expected to boost the price of gas by 3.9 euro cents per litre (5.84 Canadian cents) and the price of diesel by 7.6 euro cents (11.39 Canadian cents) per litre in 2018.

But in reality, the price of diesel in France has gone up by about 20 per cent over the past year to approximately €1.49 (C$2.23) per litre, according to the website Carbu. The average price last year was €1.24 (C$1.86) — a rise of 37 Canadian cents. That’s more than the expected 10-cent rise.

French President Emmanuel Macron has blamed higher oil costs for part of the rise but also defended his fuel tax, saying it was necessary for environmental reasons.

Canada’s gas prices are expected to rise after April 2019, when the carbon tax takes effect.

By 2022, the price on carbon pollution is expected to add 11.6 cents per litre to the cost of gasoline and 13.7 cents per litre of diesel.

A big difference between Canada’s carbon tax and France’s carbon tax is where the money is going. In the provinces that will use Canada’s carbon tax instead of their own plan, 90 per cent of the revenue from the taxes are expected to be refunded during tax time, the government says.

In France, the revenues will be used to tackle the national budget deficit.

Of the €34 billion ($38.71 billion) the French government will raise on fuel taxes in 2018, a sum of only €7.2 billion is earmarked for environmental measures.

“Although the carbon tax in B.C. is still fairly low, when it was introduced, the funds it raised went to community projects, schools, etc., so people saw that it had benefits elsewhere in their lives,” Simon Dalby, a specialist in the political economy of climate change at Wilfrid Laurier University, told Global News.

“The problems with carbon taxes come when there aren’t practical alternatives for people to cope when prices rise.”

Francois Gemenne, a specialist in environmental geopolitics at SciencesPo University in Paris, said the riots are not only about fuel costs — but it was the last straw for many.

“This is something that has been boiling for a couple of weeks… there are growing inequalities in French society,” he told Global News.

Macron promised to make the environment a priority when he was elected 18 months ago, but he also promised economic reform.

His tax policies have alienated many in the middle class — and analysis of the 2018-19 budget showed incomes of the poorest households would get worse under his plans.

Critics also say the fuel tax will disproportionately affect residents of rural areas — fueling claims that Macron is out of touch with the French people.

*with files from Reuters and Global’s Josh Elliot and Jeff Semple

Comments