They rarely get mentioned during Remembrance Day and Armistice Day tributes, but hundreds of thousands of Muslim soldiers fought for the Allied cause during the First World War — around 885,000, according to the British Royal Legion.

Some 400,000 of them hailed from the British Indian Army, whose 1.5 million troops comprised the largest volunteer force in history.

Now, a century after Muslim soldiers from South Asia, North Africa and elsewhere went to war for their colonial masters, a U.K.-based campaign is working to shed light on their oft-overlooked sacrifices.

The idea is to give overdue appreciation for the Muslim contribution to the war effort and use the stories of Muslim soldiers to counter Islamophobic and anti-immigrant narratives in Europe and North America.

READ MORE: As Canadians mark Remembrance Day, world leaders warned of ‘old demons’ rising again

“Many far-right activists and sympathizers in Europe say and believe, ‘Muslims have never done anything for us,'” wrote Hayyan Bhabha, executive director of The Muslim Experience. “The truth is one which they can’t deny. They (Muslim soldiers) made the greatest sacrifice. They died for you too. Hundreds of thousands of them.”

The Muslim Experience is a project of Forgotten Heroes 14-19, a non-profit organization set up by Belgian aeronautics executive Luc Ferrier in 2012. Ferrier is not Muslim, but he was inspired to set up the foundation after discovering the diaries of his great-grandfather, a soldier in the First World War.

“I was impressed by the enormous respect he had for his Muslim brothers in arms from all these continents, while he himself was a very devout Christian,” Ferrier told Emirates-based newspaper The National.

His NGO’s research effort suggests the number of Muslim soldiers who fought for the Allies exceeds 2.5 million, nearly three times as high as the British Royal Legion estimate.

WATCH: On First World War centenary, Macron warns of nationalism in speech as Trump looks on

Forgotten Heroes 14-19 unearthed some 850,000 original documents drawn from 19 countries, spanning journals, field reports and diaries in Arabic, Hebrew, Farsi, Urdu and other languages, each in their own way telling the incredible stories of the Muslim soldiers who stood with the Allies during the war from 1914 to 1918.

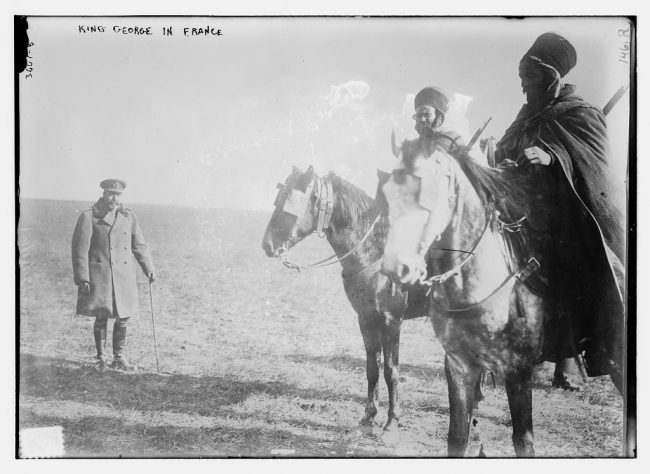

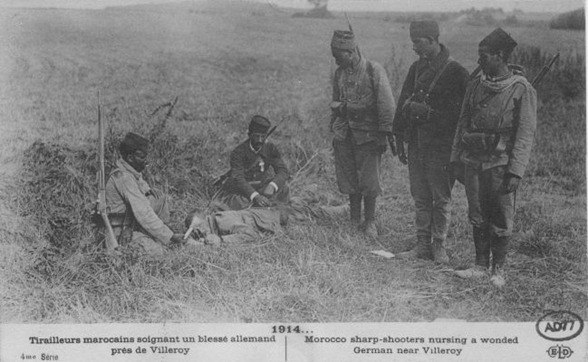

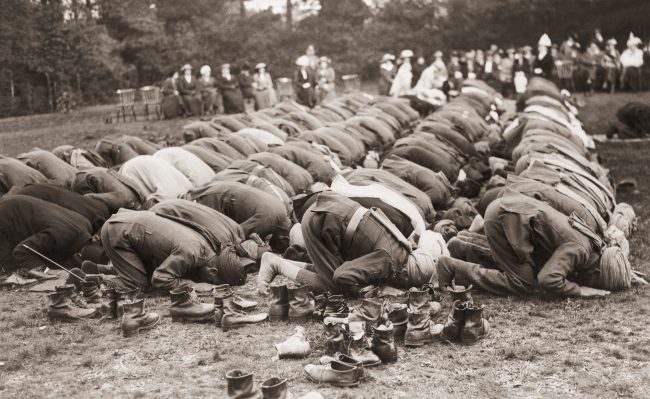

There are also photographs, some of which are truly remarkable.

One shows King George V on the front lines in France, breaking protocol by dismounting his horse to pay his respects to Algerian soldiers on horseback.

Another shows Moroccan soldiers caring for a wounded German prisoner-of-war in Villeroy in north-central France.

Allied officers are reported to have expressed surprise at the humane way in which the Moroccan troops insisted on caring for German prisoners.

“When the officers asked why they behaved with this courtesy towards German prisoners, they explained that according to the Qur’an, Hadith and examples of the Prophet, prisoners must be cared for and fed in a dignified manner,” says Bhabha. “This was jaw-dropping for the officers.”

READ MORE: The Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca explained

The stories uncovered by the foundation also speak to the camaraderie among men of different faiths uniting for a shared military cause.

Get daily National news

There are stories of Muslim imams, Christian priests and Jewish rabbis learning each other’s funeral rites so that they could lay to rest soldiers of different faiths who perished on the battlefield, says Bhabha.

In December 1914, five months into the war, the French Minister of War Alexandre Millerand instructed members of his military to learn the Shahada — the Muslim declaration of faith — so that they could recite it for dying Muslim soldiers unable to do so themselves.

Troops were also required to learn how to bury Muslim soldiers per Islamic tradition, ensuring that their faces and graves faced the direction of Mecca.

“This practice is feasible and it will be necessary to comply with it,” wrote Millerand in a letter seen on page 58 of The Unknown Fallen, a book written by Ferrier.

The British Indian Army supplied the most decorated Muslim soldiers of the war, many of whom went on to be awarded the coveted Victoria Cross by King George V.

Perhaps the most famous was Khudadad Khan, a machine gunner who was among 20,000 Indian troops dispatched to help tired British troops tackle the advancing Germans in Boulogne in France and Nieuwpoort in Belgium.

Khan’s division was outnumbered five-to-one, but they fought on until they were completely overrun, according to the U.K. Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

READ MORE: Canada’s Remembrance Day ceremonies mark 100-year anniversary of First World War armistice

The 26-year-old sepoy managed to gun down five enemy soldiers despite being wounded himself. He would be the sole survivor from his regiment in that battle, pretending to be dead before later crawling back to his regiment under the cover of night.

The bravery of Khan and his comrades is credited with buying the Allies time to muster up British and Indian reinforcements who would later halt the Germans from reaching key strategic ports.

Khan was later decorated with the Victoria Cross by King George V at Buckingham Palace.

Mir Dast was also honoured with the Victoria Cross. Born in modern-day Pakistan, he arrived in France in March 1915, a lieutenant with over 20 years of military experience behind him.

The following month, his division was instructed to mount a counter-attack against the Germans, alongside French troops.

The Germans released chlorine gas, prompting many soldiers to retreat. But Dast was among a small number of troops who managed to hold their position until nightfall.

He is credited with helping to shepherd eight British and Indian officers to safety, evading heavy fire along the way, notes the U.K. Foreign & Commonwealth Office. King George V presented him with his Victoria Cross on the grounds of the Brighton Pavilion.

Shahamad Khan, a Punjabi Muslim corporal, was awarded the Victoria Cross for “most conspicuous bravery” in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) in April 1916, according to the U.K. Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

Khan’s Victoria Cross citation notes that he worked his machine gun single-handedly for three hours under very heavy fire, after most of his men were killed.

“For three hours he held the gap under very heavy fire while it was being made secure… But for his great gallantry and determination our line must have been penetrated by the enemy,” reads his citation.

However, it wasn’t all glory and accolades for Muslim soldiers who fought on the front lines.

The book For King and Another Country: Indian Soldiers on the Western Front contains accounts of the trauma of some Indian soldiers who were experts in hand-to-hand combat with rifles and bayonets, but had never previously had to contend with bombs, shell fire and aerial assaults.

“No one who has ever seen the war will forget it to their last day,” wrote a soldier of Pashtun ethnicity, who likely hailed from modern-day Pakistan or Afghanistan.

“Just like a turnip is cut into pieces, so a man is blown to bits by the explosion of a shell… In taking a hundred yards of trench, it is like the destruction of the world.”

The book also contains a grim description of the death of one Muslim soldier as recorded by Capt. Roland Grimshaw, an officer with the 34th Poona Horse regiment and a prolific diarist.

“The killed was Ashraf Khan, one of the nicest fellows. Both his legs were blown off below the knee, and one arm, and half his face,” wrote Grimshaw. “Poor Ashraf Khan, an only son, and his mother a widow… I had him carefully put on one side where he would not be flung about or trampled on, till I had time to bury him.”

READ MORE: In historic first, 2 Muslim women elected to Congress in 2018 U.S. midterms

The Muslim Experience’s Bhabha says stories like these are crucial to giving younger generations a more inclusive picture of how the First and Second World Wars were fought and won.

“We believe that if young people are taught a more diverse and inclusive First World War and Second World War narrative in schools then they will recognize that people of all backgrounds, faiths, nations and cultures also made sacrifices that contributed to the history and security of Europe, and indeed the world,” he said.

The project, the stories it uncovered and their potential to tackle far-right narratives have received high praise from British government and military officials.

“The origins and motivations for the involvement of these brave Muslim soldiers in a European war reflect the complex, at times painful, international circumstances of the time,” wrote Gen. Nick Houghton, the U.K.’s former chief of defence staff, in an endorsement letter for the Forgotten Heroes 14-19 Foundation.

“All the more reason to honour and remember the selfless and courageous conduct of individuals in a cause that was not obviously their own.”

U.K. Conservative Party MP Stuart Andrew, former chair of the all-party parliamentary group on Islamophobia, hailed the Muslim Experience project for “celebrating the previously unknown diversity of soldiers” who fought in the First World War.

“With rising anti-Muslim sentiment today, it is important to recognize the scale of their valiant contribution to Europe’s history and security,” said Andrew.

WATCH: Canada’s 100 days — Key battles from the First World War

Bhabha says he hopes that the stories of Muslim contributions to the war will help shatter dialogue that portrays Muslims and immigrants as burdens on Western countries.

“Our projects uncover inconvenient truths about Muslims, which far-right movements across Europe and North America can’t face,” said Bhabha.

“Furthermore, what we have discovered undermines the ‘clash of civilizations’ narrative they promote by showing how Muslims, Jews, Christians, Sikhs, Hindus and others got along just fine 100 years ago during a time of great upheaval.

“If people with many differences could accept and embrace each other during wartime 100 years ago, there’s no reason people can’t do the same in peacetime today.”

Comments