On May 18, 1980, Mount St. Helens blew its top, killing 57 people.

It’s an event many people in B.C. remember: ash easily made its way to Metro Vancouver, and some of it even travelled as far as Edmonton.

According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the threat of a repeat remains very real.

Mount St. Helens is one of four U.S. volcanoes within a few hours’ drive of Metro Vancouver that have been designated as a “very high threat” by the USGS.

The ranking comes as the agency updates its National Volcanic Threat Assessment for the first time since 2005.

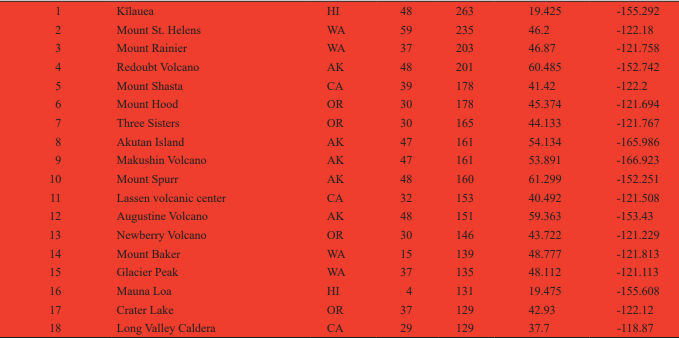

Mount St. Helens and Mount Rainier are in slots two and three on the threat assessment, while Mount Baker and Glacier Peak are in slots 14 and 15.

All four volcanoes were also classified “very high threat” in the 2005 assessment, and Baker and Glacier have actually dropped a few slots in the threat ranking.

Overall, 18 volcanoes earned a “very high threat” ranking, with Hawaii’s Mount Kilauea taking the top slot due to the heavy urbanization around it.

Not ‘going to erupt tomorrow’

But while at least one of the four high-threat Washington state volcanoes is visible from Vancouver, that doesn’t mean locals should be ducking and covering any time soon, according to experts.

That’s because the USGS threat assessment doesn’t necessarily relate to the actual likelihood of an eruption, says Stephen Malone, retired director of the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network and professor emeritus of earth and space sciences at the University of Washington.

WATCH: From the Archives: Anniversary of Mount St. Helens eruption

“Being very high risk doesn’t mean it’s going to erupt tomorrow. It just means those are the volcanoes that need more study or more monitoring, or at least evaluation,” he said.

Get daily National news

“It’s not a direct reflection of any type of immediate risk or change in risk.”

READ MORE: Hawaii volcanic eruption that created a new peninsula could last as long as 2 years

Government scientists used various factors to compute an overall threat score for each of the 161 young active volcanoes in the U.S. The score is based on the type of volcano, how explosive it can be, how recently it has been active, how frequently it erupts, whether there has been seismic activity, how many people live nearby, if evacuations have happened in the past and if eruptions disrupt air traffic.

Malone said the threat ranking serves primarily as a guiding document for scientists and policy-makers to help prepare for emergencies and to prioritize research and monitoring within existing budgets.

Building up that capacity is of crucial importance, said Denison University volcanologist Erik Klemetti, who explained that the U.S. is “sorely deficient in monitoring” for many of the so-called Big 18.

“Many of the volcanoes in the Cascades of Oregon and Washington have few, if any, direct monitoring beyond one or two seismometers,” Klemetti said in an email. “Once you move down into the high and moderate threat (volcanoes), it gets even dicier.”

WATCH: Lava bomb from Kilauea hits Hawaii tour boat, injuring 23 passengers

Brett Gilley, a senior instructor in UBC’s Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, said that despite their proximity, there would be little actual threat from any of the listed volcanoes north of the border.

“(The threat is) not as bad as people might otherwise think,” he said.

“The things that we worry about are explosive potential right around the volcano… volcanic landslides within the valleys, pyroclastic flows. Lava is actually the least of our worries. And then pyroclastic clouds,” he said.

“We would only be worried about an ash cloud from Mount Baker or Mount Rainier in a very low circumstance, so the wind would have to be blowing in the right direction.”

Mount St. Helens, located about 500 kilometres south of Vancouver, remains the Washington volcano most likely to erupt, according to Malone,

However he said its relative distance from any major population centres lowers its risk factor and that airline flight paths would be most at risk in an eruption.

Gilley agreed that the threat to air traffic remains the biggest risk. However, as the recent volcano eruption in Iceland demonstrated, aviation officials have become adept at avoiding the risk, he said.

“In the past, geologists would get excited when volcanoes went up, but no one would call air traffic,” said Gilley.

“The ash will actually scout the windows so you can’t see, and they’re still hot so they actually weld to the engines and they tend to stall the engines.”

Mount Rainier, which is about 320 kilometres from Vancouver, remains a very real risk for thousands of Americans, according to Malone, with growing residential areas in nearby valleys along with hazardous geological factors.

“Very big, lots of ice and snow up there, fragile rock, relatively recent — that is, in the geologic past — activity, that has generated hazardous conditions at some distance from the volcano.”

WATCH: Canadians among Mount St. Helens cave exploration testing NASA technology

But Mount Baker, just 23 kilometres south of the border and visible on a clear day, qualifies as a threat mostly because of where it is, Malone added.

“Its likelihood of serious eruptions is probably down the list,” he said.

“It’s a volcano that is, in some ways, slightly less hazardous. But it is a modest risk because there’s a significant population centre nearby.”

Natural Resources Canada estimates that in an eruption, Mount Baker would likely spew ash to the east with an “extremely low” chance of that debris falling on Metro Vancouver.

Malone said people shouldn’t look at the USGS’s threat assessments and worry, but he added that while volcano science has improved, it is still limited in its predictive abilities.

“Volcanoes, when they do become restless, they usually don’t tell you very far in advance,” he said.

“For example, in the case of the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, there really wasn’t any indication it was getting ready to erupt more than a week before its first small steam explosion, and that was about two months before the big eruption.”

-With files from the Associated Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.