Whether you’re figuring out your first career path or looking to change directions, a new series from Global News, Hot Jobs, focuses on career strategy for a new era in work.

Terry Reid never worried about holding down a job during the 15 years he worked in oil and gas.

Reid, an environmental engineer, moved to Calgary from Deer Lake, N.L., in 2000. He was laid off during the 2008 recession, but his unemployment stint was brief and seemed par for the course in a commodity-based industry prone to highs and lows. Calgary felt insulated from the recession, he says, a thought that seemed validated when he quickly picked up a new job.

But in 2014, as the price of oil dropped, Reid started to brace. The project he was managing for Suncor in Fort McMurray was winding down and the company was reducing travel, stripping expenses from its budget.

“I could see the writing on the wall,” he says.

In February 2015, Reid was let go. He wasn’t worried, at least not in those first few weeks. But as his job search stretched on and headlines blared about more and more layoffs, he started to realize this downturn was different.

“I just started riding this roller coaster of looking for work.”

Reid’s not alone in his job quest. More than 52,500 industry jobs disappeared in 2015 and 2016, according to the Petroleum Labour Market Information (PetroLMI) division of Energy Safety Canada. Four years later, the Canadian oil and gas industry labour force is 25 per cent smaller than it was during its peak in 2014 when it employed more than 226,000 people.

WATCH: Here’s what it take to earn a middle-class income in several cities across Canada

Those who remain committed to the oil and gas sector face a smaller industry, fewer major investments that hold the promise of new jobs, and technology’s job-altering encroachment. Will oil and gas jobs bounce back? Or is the heyday of some of Canada’s best-paying gigs over?

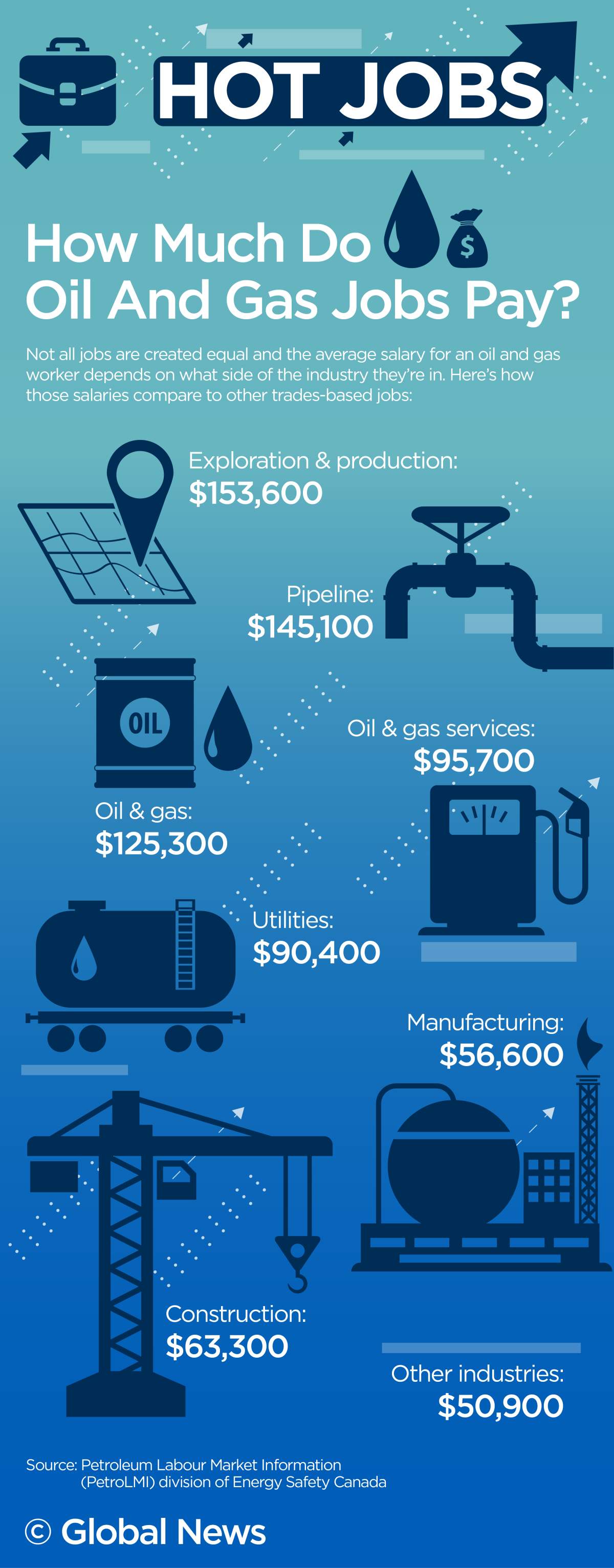

While 2017 was certainly a “low point for jobs,” says Ben Brunnen, vice-president of oil sands with the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), “those that are employed in the sector can continue to earn the highest average weekly wages in the country.”

Watch below: More than 60,000 people in Alberta’s oil and gas industry lost their jobs during the latest downturn. Things are turning around and some are slowly headed back to work. But as Quinn Ohler reports, the jobs are not what they once were.

There are groups dedicated to helping people find jobs through back channels and networking and organizations designed to help people upgrade their skills for a more automated industry. But for some, the more concerning question isn’t how you go about finding one of these jobs right now, but rather, longer-term, will enough people still want them?

WATCH: From tasting chocolate to rebuilding dinosaurs — a look at some of Canada’s most unique jobs

Get weekly money news

A PetroLMI report last year raised concern about labour shortages that could get worse as fewer workers were likely to enter the oil and gas job market, and an increasing number of experienced workers were leaving it.

Reid would go back if someone offered him a job, although for the most part he’s refocused his efforts on renewable energy. In the last four years, he’s taken solar thermal training courses and taught himself about energy savings by making extensive modifications to his own home.

His power bill is down to $2 a month, Reid says, “which was very exciting for me.”

He credits Higher Landing Inc., a career transformation company in the city, with helping him adjust after being laid off, to shift his focus. These days, Higher Landing’s president, Jackie Rafter, says most of the people she helps change their careers are out-of-work oil and gas workers. And while Reid would go back to the industry, she says not everyone wants to.

“They’re so disillusioned with oil and gas that they’re actually looking to get out. A lot of them don’t feel appreciated for all that they did.”

One of the more difficult aspects of the downturn was the number of mid-career folks who were laid off, Brunnen says.

“They’re in a bit of an awkward position,” he says. “They built pretty substantial levels of expertise and knowledge in a sector over time and they’re not ready to retire, but at the same time in a constrained environment companies are reticent to bring them back on.”

In the last year or so, there’s been a roughly seven per cent increase in employment, says Carol Howes, vice-president of PetroLMI. And while job numbers are substantially lower than they were during the 2014 peak, PetroLMI figures show the industry actually grew 15 per cent between 2006 and 2016.

“We have seen some jobs coming back,” Howes says, “but it’s still substantially less than the number of jobs we lost.”

Part of the problem, she says, is that there isn’t the same type of growth and large-project construction in the oil sands that there once was. Nobody is expecting any new major investments in Canada for at least the next year, Brunnen says, partly because the economy is so uncertain but also because of the federal court decision quashing the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion.

“I think investors are going to sit on the sidelines a little bit,” Brunnen says, which spells short-term uncertainty for job seekers.

“Folks are going to have to start making those harder decisions about finding alternative opportunities … it’s definitely a wait-and-see atmosphere that we’re in.”

In the current environment, Rafter says, she’s seen two camps emerge: the workers who will fight to stay in and those looking to get out.

Rafter helps the group looking for a way out change careers. She’s seen some more dramatic-seeming changes: geologists become bankers. And then she’s seen the industry’s Terry Reids, environmental engineers shifting focus and trying to find alternative sources of income to float them through the industry lows without leaving it altogether.

For those who want to stay in oil and gas, Rafter says she tries to help them tap into the more “hidden” job market, “which is still alive and thriving.”

That’s where Mike Vickers comes in.

Vickers, who came from Nova Scotia and “fell in love with the industry” started Oilfield Jobs Shop shortly after the downturn. What began as a Facebook page posting links to underpublicized oil and gas jobs is now a website aiming to position itself as the industry’s go-to for jobs.

“What I realized pretty quick is the social reach and the social aspect to this industry has never been really tapped into before,” says Vickers, who works as a field service technician, installing wellheads.

He acknowledges the job loss but is confident that more oil sands investment will come.

WATCH: These jobs are safe from robots, according to one economist

While the industry is already seeing fewer engineering and construction jobs, Howes says advancing technology is introducing new jobs, like emissions management and data-based work, to the sector.

Even as automation changes the skill requirements of employees, she says there’s a real incentive to support current employees in gaining the skills they need to move into new roles rather than purely hiring fresh. It’s a complex industry filled with workers who are already incredibly knowledgeable, Howes says, so employers “do want to marry that skill set with all sorts of new technologies.”

That doesn’t mean the oil and gas industry isn’t still trying to attract new workers or that there are no opportunities. It’s a challenge to recruit young people to some of the colder, more remote communities for shift work, Howes says, but the industry still retained one advantage that it had before the downturn.

“The salaries are very attractive.”

Comments