The three tornadoes that touched down in the Ottawa-Gatineau region left demolished houses and uprooted trees in their paths and two people with critical injuries Friday night.

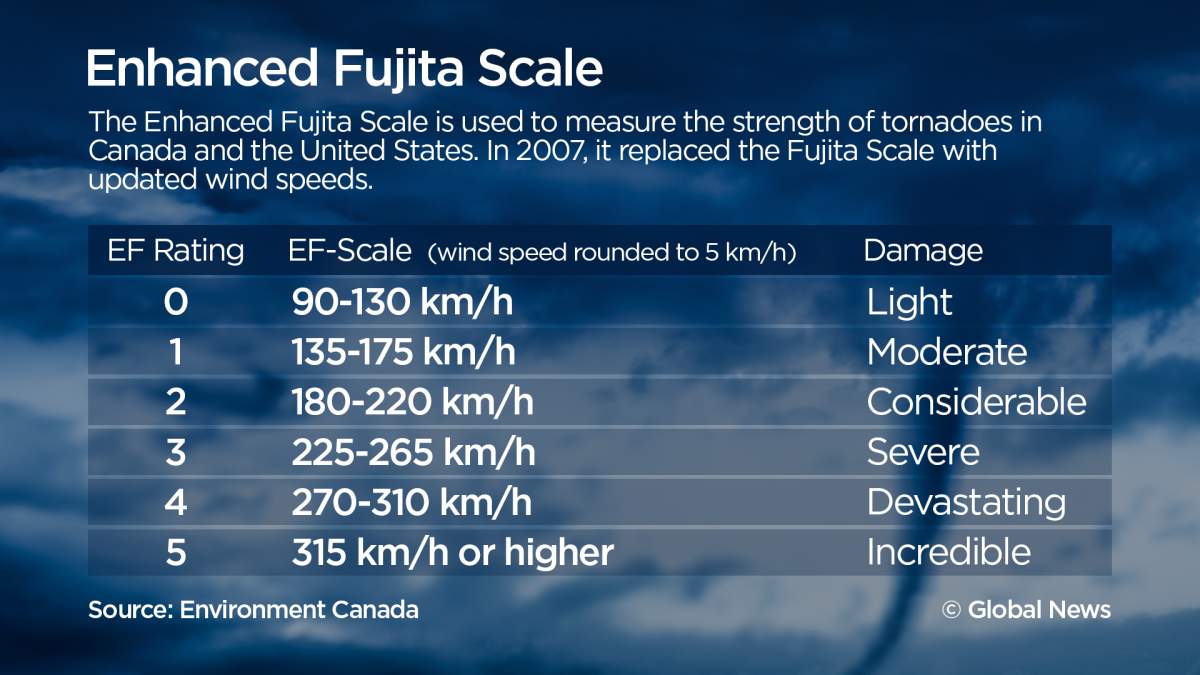

The twisters packed winds up to 265 km/h. The stronger of the two, which travelled from Dunrobin, Ont., to Gatineau, Que., was classified as an EF-3 storm, while the one that touched down in Arlington Woods, Ont., was an EF-2.

The third, which was only identified Monday night, touched down in Calabogie, Ont. with windspeeds of 175 km/h, making it an EF-1 twister.

While the Ottawa region is not immune to this type of weather, a storm of this intensity has never occurred there, Global News chief meteorologist Anthony Farnell explained.

“What made the setup on Friday particularly dangerous was that a strong ‘fall-like’ storm was interacting with near record summer heat and humidity,” Farnell said. “The timing of the front moving through Ottawa also maximized the amount of heating that occurred during the afternoon giving even more energy to the storms.”

The last time a strong EF-3 occurred in Ontario was the Goderich tornado of 2011.

The tornadoes moved quickly through their respective neighbourhoods: the Dunrobin-Gatineau tornado was on the ground for almost 40 kilometres and lasted 40 minutes. The other tornado in Arlington Woods headed for Nepean and was on the ground for less than 10 minutes.

“These supercell storms were very fast moving, which may be one of the reasons people were caught off guard even with the watches/warnings in place,” Farnell said.

“I also think people in residential areas across Canada don’t think that a storm like this could ever occur here. Hopefully, Friday’s storms helped changed people’s mentality.”

Anatomy of a tornado

Get daily National news

The tornadoes that touched down in the Ottawa-Gatineau region were supercell tornadoes. According to National Geographic, tornadoes are formed when wind shear (fast-moving winds that roll into a horizontal vortex) is combined with an updraft to create a vertical vortex. This usually occurs during a thunderstorm.

A supercell forms from that vertical vortex when you add upper–level winds. Only 30 per cent of supercells become strong enough to form a tornado.

But scientists still aren’t sure what gives the supercells an added edge that allows it to form a full-fledged tornado.

WATCH: Supercell versus landspout tornadoes

Another version of a tornado is a landspout. That’s created by heat rising from the surface of the Earth and updrafts. It starts at the ground and can build up towards the cloud, although rarely connecting. These tornadoes are less destructive on average.

Climate change and tornadoes

The larger tornado, which did extensive damage in Dunrobin and Gatineau, is the latest in a list of weather events in the past 18 months that include devastating storms and floods.

Gatineau Mayor Maxime Pedneaud-Jobin said the explanation is plain.

“In Gatineau, we’ve suffered a lot, we’re continuing to suffer and one of the main sources of that, it’s clear, is climate change,” Pedneaud-Jobin said, the Montreal Gazette reported Sunday.

“Are we going to take this threat seriously? It’s not a theory, it’s people who are displaced, people who suffered, people who have lost everything.”

WATCH: ‘It’s pretty devastating’: Homeowners in Ottawa speaks about losing home after tornado hits region

Quebec Premier Phillipe Couillard expressed similar sentiments.

“You have a living example of a global issue here, which is climate change,” he said Saturday while touring the affected area.

“We’re affected by the global phenomenon, what happens on the other end of the planet or south of our border has an impact here.”

While climate change has been linked to extreme weather, it’s not clear yet whether it has an effect on the formation of tornadoes.

A 2016 study from Columbia University found that the average number of tornadoes that are part of outbreaks is on the rise. (An outbreak is defined as a large-scale weather event with multiple tornadoes that can last days.)

The study said some scientists expect that a warmer climate produces the conditions favourable for a tornado, linking climate change to the cause of the uptick. But study author Michael Tippett also noted at the time that “our usual tools, the observational record and computer models, are not up to the task of answering this question yet.”

Another study linked an extended tornado season with climate change – according to Diffenbaugh et. al in the journal PNAS, a simulated change in the atmosphere showed a possible increase of the number of days which supported tornadic storms, though the results were based on a simulation.

“The tornado season in Ontario typically lasts from May through September with peak season in June and July,” Farnell explained.

“It’s not unheard of but it is unusual to get strong tornadoes in late September.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.