OTTAWA – Canada’s spy agency wants to shield the identities of five current and former employees from the public when they testify in the lawsuit of a Montreal man who was detained in Sudan – prompting vehement objections from the man’s lawyer.

In newly filed court documents, federal lawyers say the Canadian Security Intelligence Service identities must be kept confidential in order to protect the individuals from personal harm and to ensure the service can continue to work effectively.

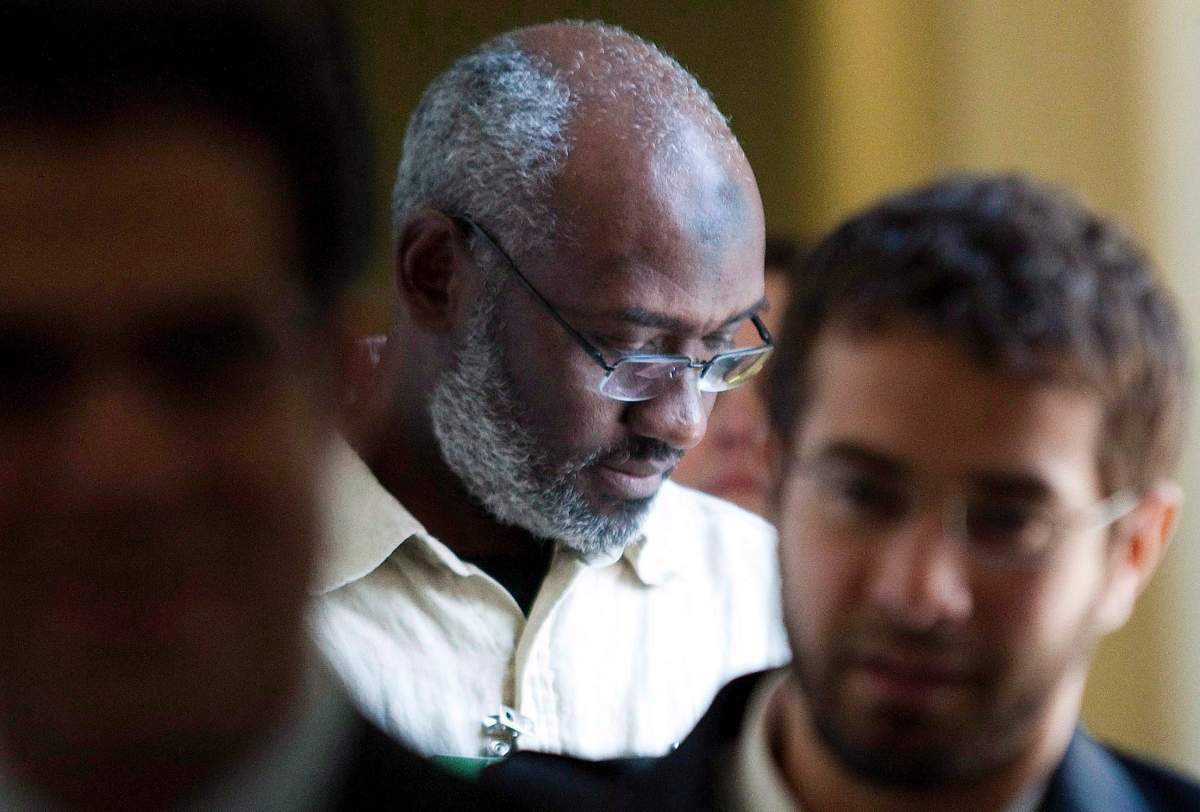

It is the latest legal spat in the long-running case of Abousfian Abdelrazik, who is suing the Canadian government for an apology and compensation over his lengthy overseas detention.

Abdelrazik, 56, arrived in Canada from Africa as a refugee in 1990. He became a Canadian citizen five years later.

He was arrested during a 2003 visit to Sudan to see family. In custody, Abdelrazik was interrogated by CSIS about suspected extremist links. He claims he was tortured by Sudanese intelligence officials during two periods of detention, though Canada says it knew nothing of the purported abuse.

WATCH: CSIS’s extremist probe ended months before Quebec Mosque shooting

Abdelrazik denies any involvement in terrorism, and civil proceedings against the government are slated to begin Monday in the Federal Court of Canada.

Get daily National news

The federal lawyers, backed by an affidavit from a senior CSIS official, are asking the Federal Court for an order that will permit the spy service witnesses to testify in open court while ensuring their names and physical appearance are kept from the public, Abdelrazik and his counsel.

All five employees have “worked in a covert operational capacity” and divulging their identities would put them at risk of personal harm, given the threats that are frequently made against the service and its employees, the federal submission says.

The government proposes the five “protected witnesses” be allowed to enter and leave the courtroom via a special entrance, take an oath in a separate room and testify while hidden by a screen or through videoconference in a manner that obscures their faces.

The witnesses would provide their real names in writing to the judge and the required court staff prior to testifying.

In their submission, federal lawyers say the arrangement “strikes an appropriate balance” between the traditional tenet of open court proceedings and the need to maintain secrecy. “The open court principle is not absolute, and must, in appropriate cases, be limited for reasons of national security, the safety of individuals, and the proper administration of justice.”

Abdelrazik’s lawyer, Paul Champ, calls the federal request “a gross overreach.”

“In some cases the identity of undercover police officers are protected, but it’s only for a limited period and with evidence of a specific danger or threat. There is none of that here. And why should CSIS get more protection than the police?” Champ said.

“There needs to be accountability and those responsible should not be allowed to hide in the shadows.”

He plans to file written arguments with the court opposing the confidentiality demands later this week. This disagreement is not expected to delay the trial as the witnesses are not scheduled to appear for several weeks.

The federal submission notes the CSIS Act makes it an offence to name an employee “who was, is or is likely to become engaged in covert operational activities” of the service.

Senior CSIS personnel who appear in public forums are typically identified publicly. Current CSIS director David Vigneault is expected to testify openly at the Abdelrazik trial.

However, federal lawyers contend the five other witnesses in question must be shielded given the threats to intelligence personnel posed by terrorist organizations such as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant and hostile intelligence looking to exploit such opportunities.

They also cite the recent British charges against two alleged Russian intelligence officers in relation to the attempted murder of double agent Sergei Skripal, his daughter and a police officer with a military-grade nerve agent.

Threats against CSIS personnel have also come from individuals encountered during spy service investigations, says the affidavit from the senior spy service official, identified only as “David” in keeping with the agency’s arguments for anonymity.

“These have included threats uttered during interviews, projectiles thrown at cars, being approached with weapons and receiving threatening voice messages,” says the affidavit.

- Olympic medallist wins bronze, confesses on live tv to cheating on girlfriend

- Parents condemn $176 fines for hostel staff after daughters died from tainted alcohol

- Canadians wait for flights out of Cuba, aid struggling to get in amid U.S. energy blockade

- Pam Bondi hearing gets heated as Congress questions her on Epstein files

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.