Global News is a media partner with Journalists for Human Rights and, as part of that partnership, is proud to provide a platform for updates on JHR programs.

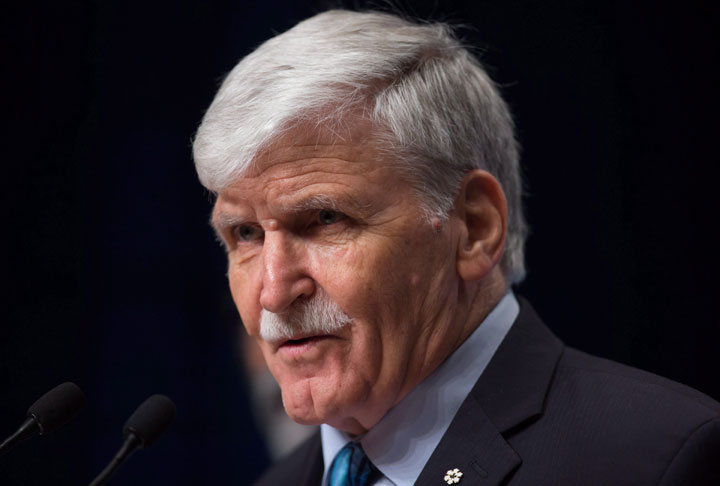

Retired lieutenant-general and former senator Roméo Dallaire’s experience watching the Rwanda genocide convinced him that journalism is crucial in fragile states and conflict zones. Journalists for Human Rights’ executive director Rachel Pulfer sat down with Dallaire for a short interview to discuss the importance of reporting in areas with instability and social unrest.

RP: When you spoke at JHR’s Night for Rights last year, you started by asking journalists where they were “when I needed you in Rwanda.” Why?

RD: Let me put it this way: I was there since the previous August, and the genocide started the following April. Although there had been a civil war between the government and the rebels, they had signed a peace agreement, which garnered a bit of publicity. After that, for the rest of the year until the genocide, Rwanda fell off the radar of the media.

The political impasse created a degenerating situation that led to the explosion. But next to no reporting at all was done by the media, written or electronically. To me, journalism is not just reporting on what has happened but also what is going on, anticipating and influencing what is to happen. Even though there were riots and assassinations, tensions between sides, unexpected returnees, there was next to nothing that was published. All these were factors that led to the genocide exploding — but no journalists were present at all.

Get daily National news

I have no problem on reporting when a conflict is happening and providing the information, but there is an acute absence of anticipating, of being aware, reading the tea leaves and preparing people to listen to those who are giving warning signs that the whole thing is going to be catastrophic.

I recognize that journalists are caught up with budgets, but to me it’s an indication that journalists are not sufficiently informing people in how to participate and actually influence the future. The goal is not to be a passive entity in regards to crisis.

RP: What are your thoughts about the value of media development in fragile states and conflict zones?

RD: You have to work diligently at building an objective, credible, journalistic capability in the nation, to ultimately say that you have free speech that gives voice to the people, and we are all the more required to do that in countries where it is difficult for this to happen because … the more the country is in crisis, the more the country is at odds, the more you have to produce journalists with those skills. Journalists have to be credible, and it is not just by helping them do more local reporting but also helping them be the critics, that is part of the nation becoming democratic. There is a price in becoming democratic; it is not only politicians that are killed, journalists are on the front lines, too. You are on the front lines.

There is a price to truth. There is a price to peace also, but in peace you have to tell the truth. Like the soldiers who pay the price of truth, it is people like eminent academics, the judicial system and journalists who are the references that a society needs in order to be able to feel (free). You are in the front lines of that.

RP: How is your own initiative, the Roméo Dallaire Child Soldiers Initiative, working with media?

RD: We are doing work with radio stations to educate and inform the youth of South Sudan and Sierra Leone. Eminent journalists and other credible workers should be able to talk to young people as well as adults. That way, you can reinforce the education of young people to prevent their recruitment into militia as children, and instead include them as part of the peace and reconciliation process.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.