On Dec. 11, 1987, three inmates at Burnaby’s Oakalla prison crawled through a hole in the wall, scaled a fence, ran through the streets of a quiet residential neighbourhood to a nearby SkyTrain station and hopped on a train — still dressed in prison garb.

At the time, officials decided not to inform the public of the escape, a decision that angered local residents and politicians.

It also angered at least one of the escaped inmates. Fugitive Heath Thompson, 18, called a local radio station to say he found it “strange” their daring escape hadn’t gotten much attention.

“I was expecting to see it on the news — three guys escaped from Oakalla,” he said.

Less than a month later, Oakalla became a problem too big to ignore. Thirteen prisoners escaped on New Year’s Day 1988, just days after a riot destroyed a section of the prison.

In the 1980s, Oakalla was a tense place at the best of times. Built in 1912 as a prison farm, it was designed to reform prisoners and teach job-related skills.

Originally surrounded by pasture land, rows of homes popped up around the prison farm as the city of Burnaby grew. Some homes were as close as 50 metres from the fences around Oakalla.

Over the years, conditions deteriorated. The prison was over capacity, housing a volatile mix of inmates convicted of minor offences and hardened criminals awaiting trial.

During its long, strange history, 44 people were executed at Oakalla. Others underwent electroshock therapy or even had plastic surgery performed on them against their will.

- 35 court dates and no trial: Family of B.C. double homicide victims frustrated by delays

- ‘Embarrassing’: Vancouver councillor calls out mayor over drugs comment controversy

- ‘Like a spelling mistake’: B.C. teen’s DNA ‘corrected’ to cure rare disease

- Kelowna mayor does not ask for more RCMP funding during Victoria trip

“It’s just a s—hole,” one former inmate said following the closure of the prison. “A dumping ground for B.C.”

According to Burnaby Mayor Derek Corrigan, who worked as a guard there in the 1970s, it was also “probably the easiest prison to escape from in all of North America.”

There were 890 escapes at Oakalla, but it was the 1988 escape and its messy aftermath that marked the final chapter of B.C.’s most notorious prison.

Riot: ‘You’re going to see blood’

Earl Andersen, who was a 21-year-old Oakalla guard at the time, said trouble had been brewing for a few days in December 1987. The holiday season can be a tough time for inmates, a reminder of the loneliness and isolation of prison life. On top of that, most senior staff are away on holidays, leaving less experienced workers to pick up the slack.

“There was talk of an escape,” Andersen recalled. “There was talk of riots and you can just feel the tension in the place.”

On Dec. 27, two inmates were caught communicating with each other during a church service. One inmate was escorted out by a guard and a scuffle broke out.

Things calmed down and guards searched cells while inmates were in the yard. One guard told the inquiry he heard threats from inmates as he went about his rounds the following day.

“Tonight’s the night,” the inmates said, according to the inquiry. “You’re going to see blood. We’re going to break this place up.”

Another search of cells was ordered. This time, guards found two brass rods, one of which had been sharpened to a point.

Inmates accused guards of planting the shanks, makeshift weapons, in their cells.

At that point, as one officer told the inquiry, “everything broke loose.”

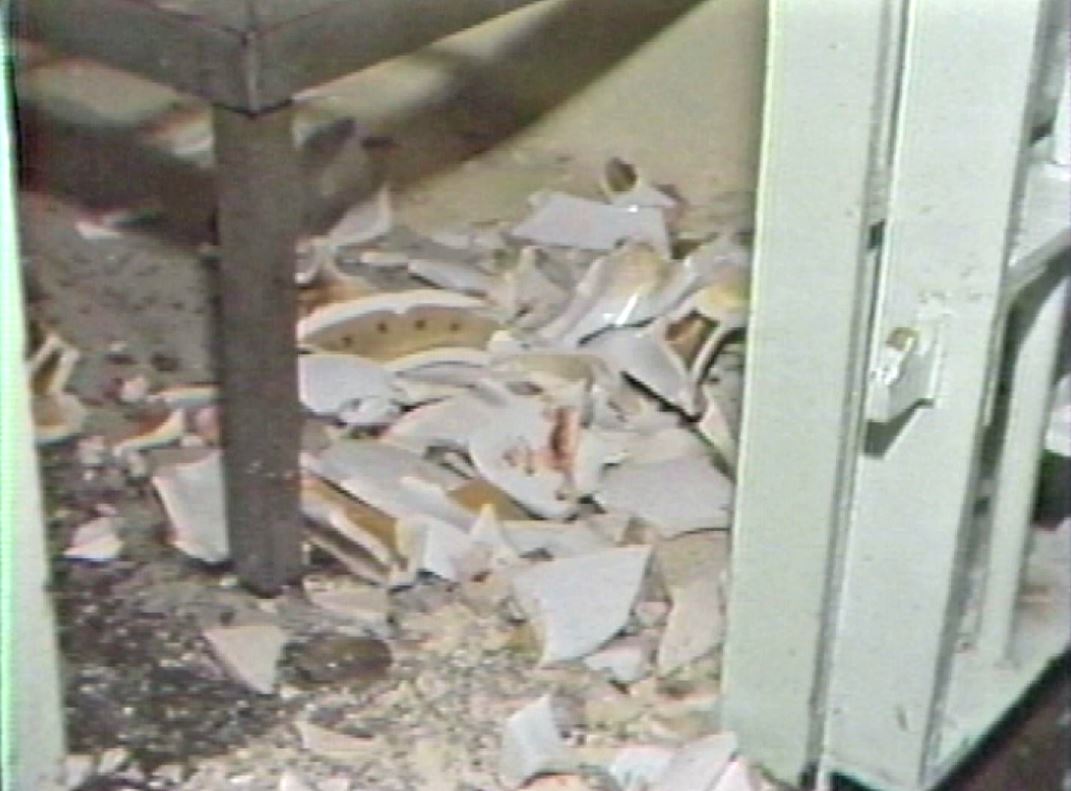

Andersen was standing in a central part of the prison and could hear the sound of smashing porcelain.

“I just remember catching something out of the corner of my eye and I realized what was happening,” he said.

“They had taken a sink and they had thrown it — with incredible force — against the end gate and it smashed into dozens of pieces, all these shards of porcelain flying everywhere.

“And I thought, ‘Oh my God, they’re going to knock this thing right off the hinges.’ And then they would have control of the whole wing and we’d be in trouble, if not dead.”

Guards tried to quell the riot by opening fire hoses to douse the flames and subdue the prisoners.

Windows were opened, apparently to clear the facility of smoke, leaving the prisoners damp and cold.

Amid the chaos, one inmate slashed his own wrists and wrote the words “Helter Skelter” in his own blood on a cell wall, a reference to convicted killer Charles Manson.

Fifteen inmates, who were considered instigators, were separated from the general population and transferred to cells located beneath a giant barn.

Get daily National news

The dank, subterranean cells may have been a perfect way to punish prisoners, but it was less than successful at containing them.

“There was sort of a misconception or a belief that because it was like a dungeon that it was very secure, but in reality, it was very insecure,” Andersen said.

Prison break: ‘Let’s do the guards’

The inmates spent a few days stewing inside the subterranean cells, which legendary broadcaster Jack Webster referred to at the time as a “disgusting, dingy, underground concrete dungeon.”

“It doesn’t belong in 1988,” he added. “It belonged in 1888 or even 1788.”

WATCH: Jack Webster visits Oakalla prison

The 15 prisoners thrown under the barn had little in the way of creature comforts.

Guards were told to treat it like any other unit, and distributed items like blankets, tobacco, disposable razors and toothbrushes. The Salvation Army also visited, giving out bags of peanuts and candy.

It wasn’t much, but it was enough for inmate Bruce McKay to hatch a plan.

“He took a strip of torn bedsheets and tied a sock full of peanuts to one end of it,” Oakalla Deputy Director Grant Stevens told BCTV, now known as Global News, at the time. “He slid the sock under a gap at the bottom of the cell door, flipped it onto a door lever, which popped the door open.

“The lever usually had a locking pin in it as an extra form of security, but on this night — for whatever reason — the pin wasn’t engaged.”

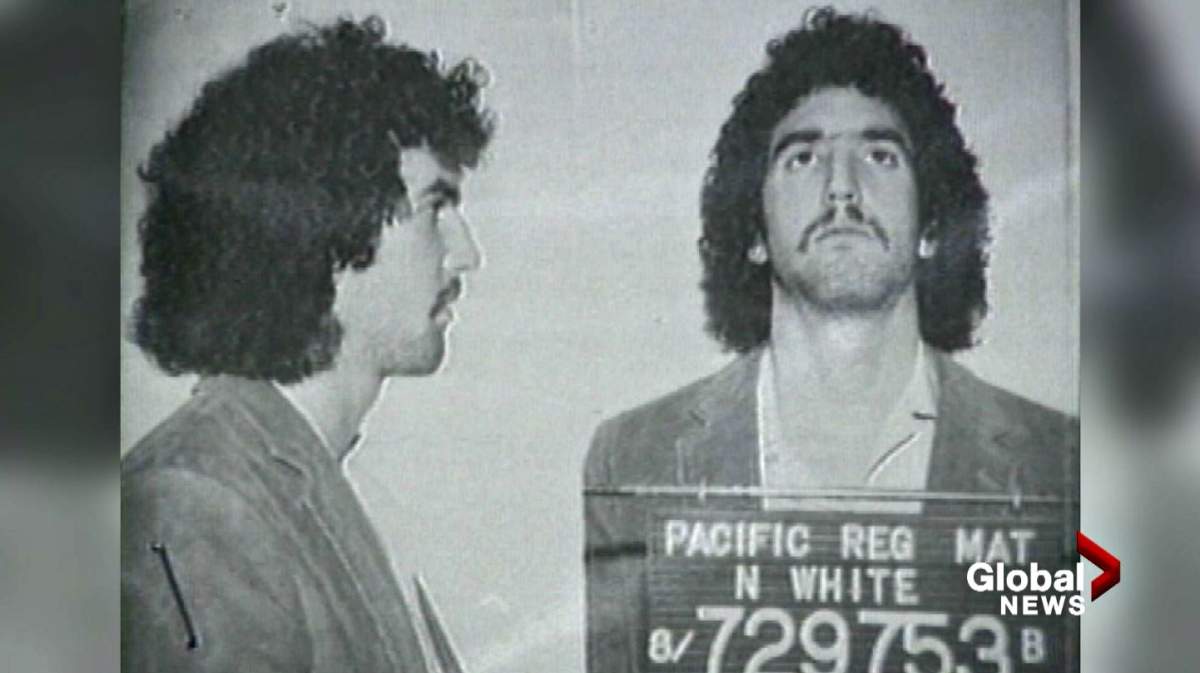

McKay walked out of the cell and quickly freed fellow inmate Neil White.

The pair had a shank, consisting of a razor blade that had been melted into a toothbrush handle.

They called a guard over, grabbed him and put the shank to his neck, cutting him and spilling blood.

WATCH: 13 inmates overpower guard and escape from Oakalla

Another guard was told to hand over the keys or they would kill his partner.

The guards were made to lie face down and their hands were cuffed behind their backs. The inmates took the keys and unlocked the other cells.

Two of the 15 inmates stayed — one because his cell door, for some reason, wouldn’t open. The other simply chose to remain in his cell.

As the guards lay on the ground helpless, they heard a prisoner say, “Let’s do the guards.”

Another chimed in and said, “No, leave them alone. You’re free now.”

Andersen said the prisoner who decided not to escape might have saved the guard’s life.

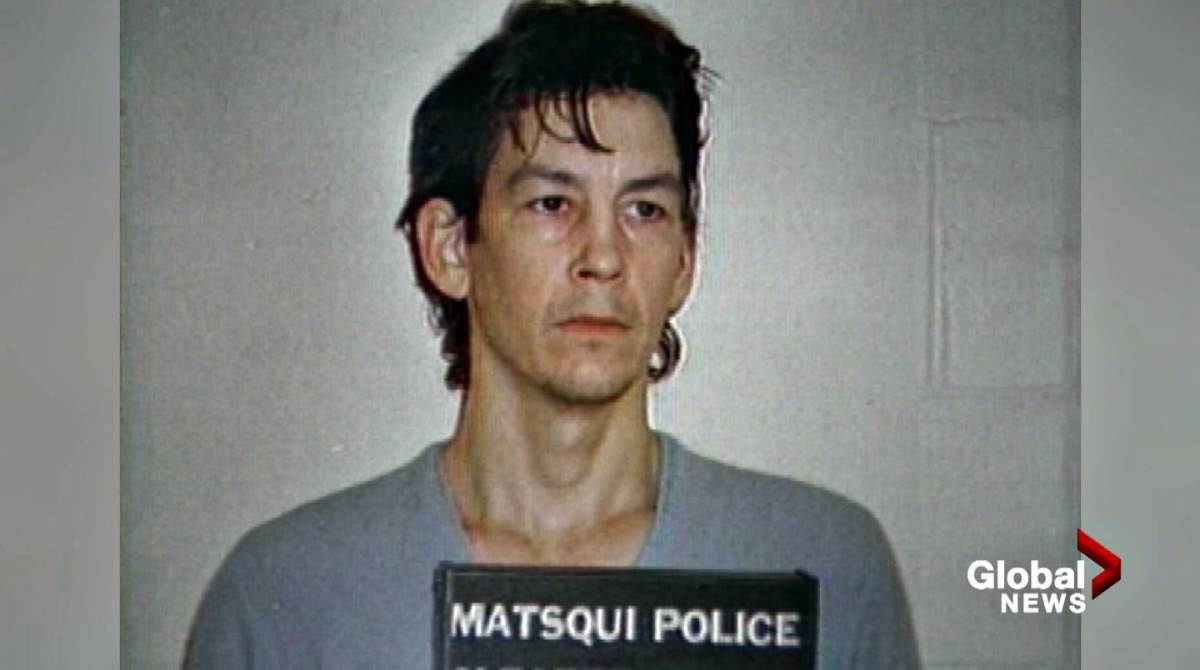

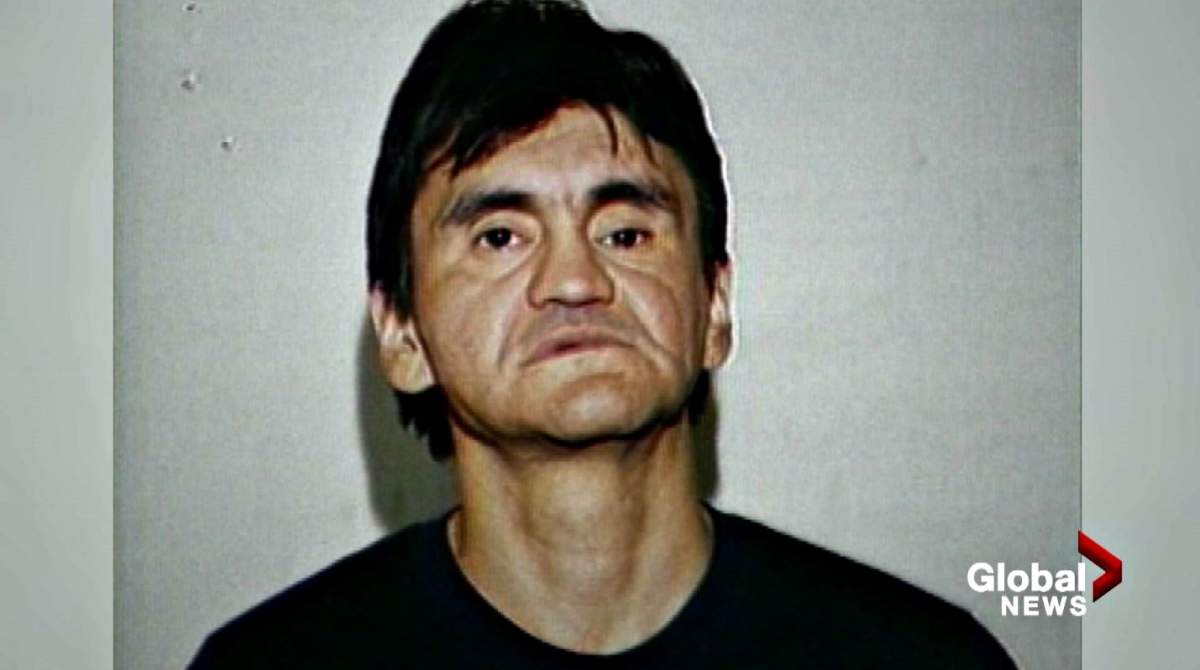

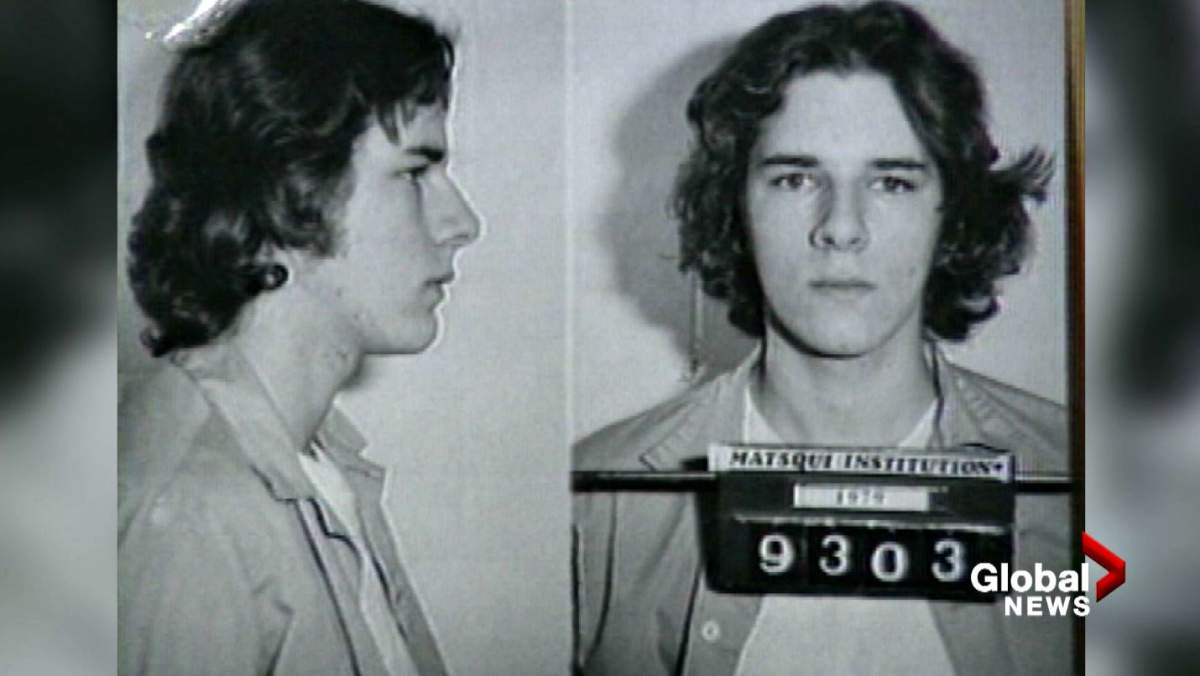

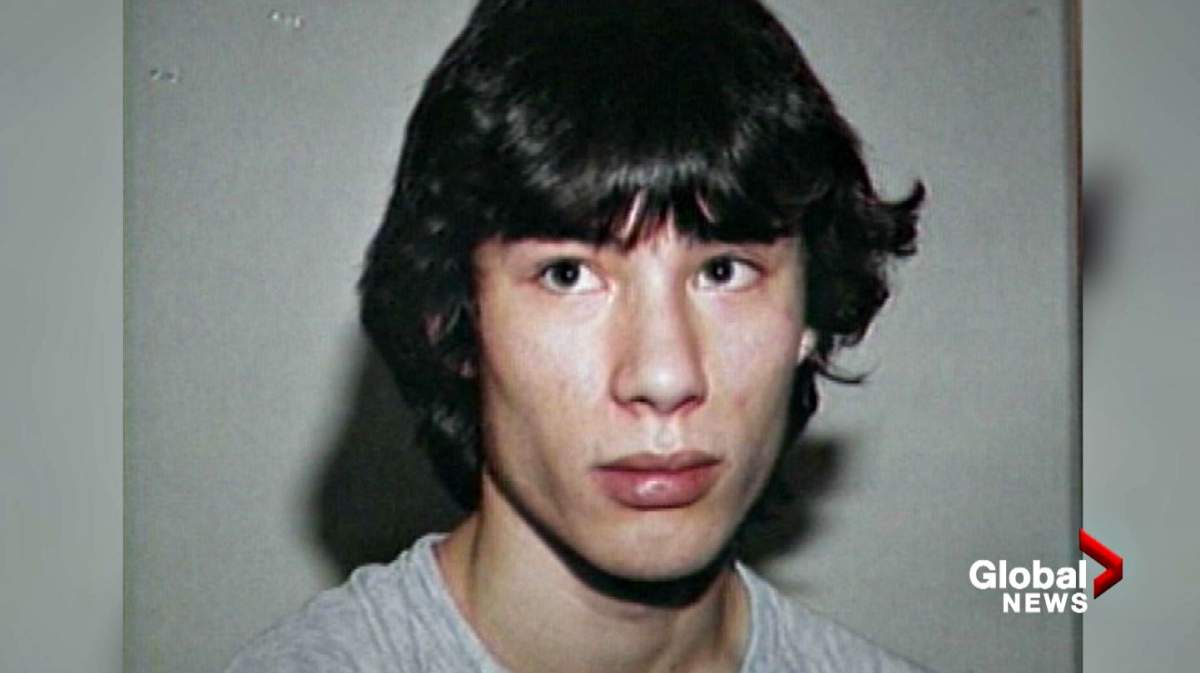

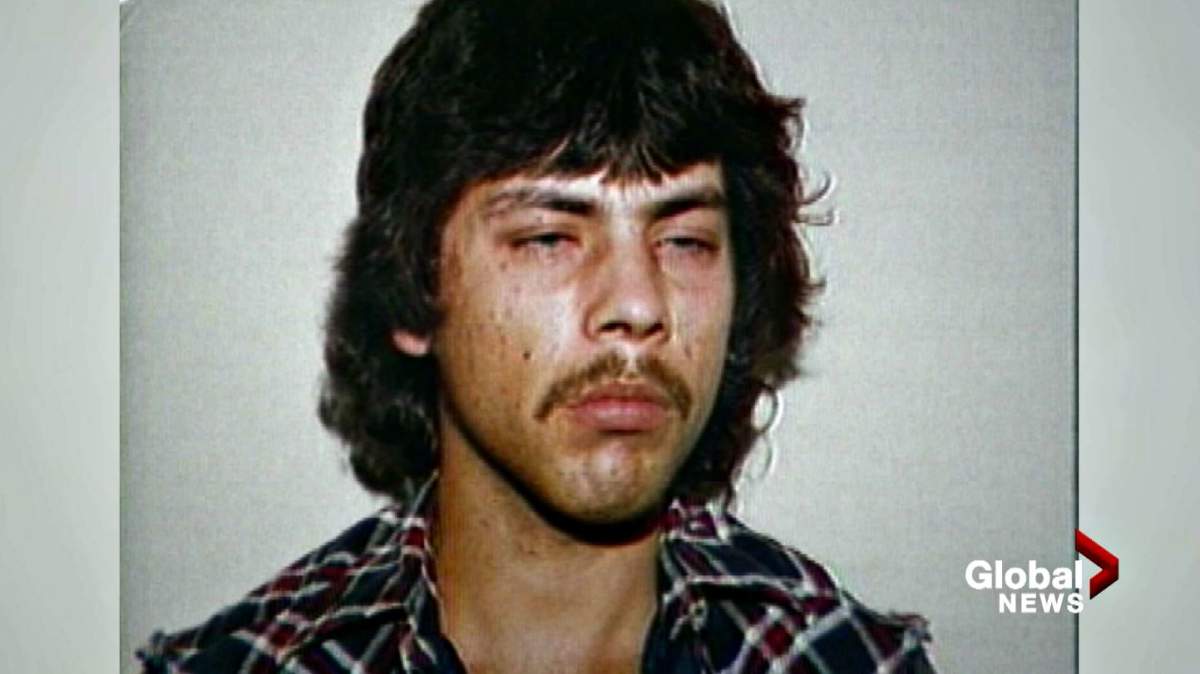

GALLERY: The inmates who escaped from Oakalla

The inmates threw the guards in a cell and locked the door. They then made a break for it, a task that was made easier since the wooden doors were kept open to allow heat into the dungeon-like cells.

Two of the inmates put on prison guard uniforms while the others remained in their usual garb.

A prowl officer was assigned to patrol the grounds, but at the time of the escape, he had been called in to cover someone who was on a break.

The inmates — who were being held on charges ranging from armed robbery to murder — climbed a fence and, as one inmate told the inquiry, “went into the night.”

On the lam: ‘It was outright panic in the neighbourhood’

Kevin Corkery was heading home from a New Year’s party at a pub with his wife when three men hauled them out of his car and one got inside.

“I tried to put up a fight,” said Corkery, who held onto the car as the prisoner drove away.

“I fell off the car. He smashed into another car and he was gone.”

Corkery’s was one of the several reports to police as the 13 escaped inmates scattered across Metro Vancouver.

Some prisoners’ freedom was short-lived.

Gary Dewhirst, charged with first-degree murder, was caught on New Year’s Day when he went to his parents’ home in Chilliwack.

Three others — Daniel Fetter, Daniel Gordon Smith and Alan Isbister — were picked up in a bar in New Westminster later that same day.

Before his capture, Gary Hicik spent time hiding in a Burnaby apartment. According to a Canadian Press report at the time, he spent his days watching TV news reports about the Oakalla escape and “chatting up” women on the phone.

The friend who sheltered Hicik said he hid the fugitive to give him respite from the conditions.

“It’s a scumhole,” he said. “It’s a bad-attitude place. All you get in there is a bad attitude. You don’t get any rehabilitation.”

WATCH: Interview with a fugitive from Oakalla prison

BCTV reporter Alyn Edwards was at English Bay covering the annual New Year’s Day Polar Bear Swim when he was told to switch stories and cover the Oakalla escape.

He soon received a call from an acquaintance who offered to set up an interview with one of the escapees.

Terry Hall said he wanted to expose inhumane conditions at Oakalla. Edwards agreed to the meeting on the condition Hall turn himself in to authorities afterwards.

With his left hand in a cast after punching a prison cell door in frustration, Hall sat at a kitchen table and told his version of events.

“Some drunk guards were pulling out fire hoses and hosing people down,” Hall told Edwards about the riot.

“There were guards stumbling around, falling against walls. You could smell the booze right on ’em.”

“You can only push so many people so far. I think this was pushing it right to the limit.”

The interview did not sit well with B.C. Attorney General Brian Smith, who blasted BCTV’s decision to interview an escaped convict.

“That a reputable responsible news outlet would interview someone who was a fugitive from justice and then allow that person to leave … It could well have been that within a matter of minutes or hours, that person could have committed further crimes,” Smith said.

Edwards notes Hall did turn himself in to authorities, as promised, after visiting his family.

He believes interviewing Hall was necessary to expose the conditions at Oakalla.

WATCH: Interview with Oakalla prison guard

“They were living in deplorable conditions and that’s why they rioted,” he said.

Prison guards, meanwhile, countered with their own accusations of abuse.

Edwards spoke to a guard who said prisoners “spit on us, throw things at us. There have been instances where prisoners have urinated in the soup and messed with the food.”

“The morale since I’ve been there has been really horrible.”

Over the next few months, all remaining escapees were brought back into custody.

The controversy, however, didn’t go away.

The commission of inquiry, which had been ordered by then-premier Bill Vander Zalm, recommended the government “close the doors of Oakalla forever.”

Aftermath: ‘The straw that broke the camel’s back’

The sign above the entrance to Oakalla featured B.C.’s coat of arms and the provincial motto: Splendor Sine Occasu, Latin for “Splendour Without Diminishment.”

In reality, the prison’s image — due to decades of neglect — had been diminished beyond repair.

Corrigan said residents had largely accepted having a prison in their neighbourhood, but the New Year’s Day escape was “the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

“It was a place that generated economic activity, but then that corner turned and suddenly it became a deficit,” Corrigan said. “People were worried about the prison and worried about the fact that it was right in the middle of what was a growing urban community.”

During the 1986 provincial election campaign, Vander Zalm talked about closing the prison.

On June 30, 1991, the B.C. government followed through on its promise and the final inmate left.

In what is now a familiar story in Metro Vancouver, Oakalla was torn down and townhomes were built in its place.

Thousands of bricks from the exterior of a cellblock were repurposed into decorative walkways around the new housing site.

The site’s notorious past didn’t deter potential buyers, who were anxious to own townhomes overlooking Deer Lake. Interested buyers slept in their cars for up to 36 hours to save a spot in line.

Corrigan said the area is now “a really lovely little community” within walking distance of the SkyTrain.

“The people who live there very seldom seem to sell,” he said. “That generally means there seems to be a high degree of enjoyment of that particular area.

“A lot of people were forced to live there who didn’t want to and now there’s a lot of people who would like to be able to earn enough money to move in.”

— With files from The Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.