Every day, parents send their young sons and daughters off to work but in the case of Austyn Schenstead, 19, he never came back.

On Thursday, the company responsible for his death pleaded guilty after Schenstead died while on the job and to make matters worse, it was a family-run business.

“This kind of thing ruins a family,” Austyn’s mother Rebeccah Schenstead said.

Inside Saskatoon provincial court, family members wept as Austyn’s grandfather Eric described life as a bottomless chasm of pain after losing the 19-year-old who brought the family so much joy and expressed love without reservation.

“He had a great sense of humour, gave the best hugs, loved sports, loved his family — he was a family man,” Rebeccah said with tears in her eyes.

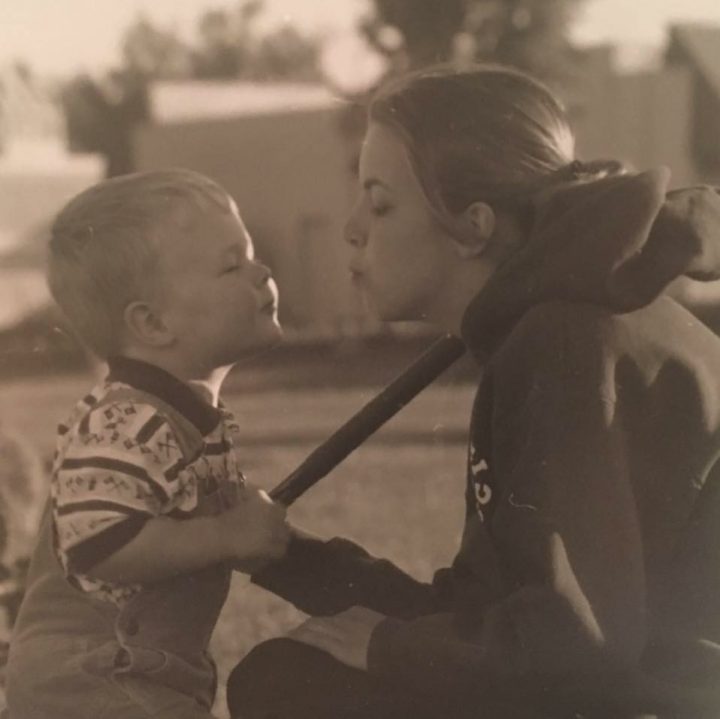

Austyn was her first born — she was 16 at the time and said the two, in a sense, grew up together.

“He was my rock.”

On Nov. 30, 2016, Schenstead was killed while Carmont Construction, a private contractor, was installing sound walls throughout the city.

Get breaking National news

Court documents show that at the time, Schenstead and another employee were removing the bracing on the panels secured around the concrete slabs.

According to the Crown, a concrete barrier slid off the truck trailer and struck the teen. Austyn was pronounced deceased on scene.

“It’s been devastating. Our family has been ripped apart,” Rebeccah said.

Adding to the enormous grief, Carmont Construction is Austyn’s stepfather’s family business.

“I have felt very strong from the beginning that they should be held accountable as if he worked for any company — family or not,” Rebeccah said.

WATCH: Man killed in Saskatoon industrial accident

In April, Carmont Construction was charged with failing to make arrangements for the use, handling, and transport of sound barrier panels in a manner that protects the health and safety of a worker, resulting in the death of a worker.

In handing down her decision, the judge became emotional, explaining she had children around the same age as Austyn when he died, and that she shared the family’s pain.

She ordered the company to pay an $80,000 fine within an allocated time period of 36 months.

“There isn’t an amount of money that will bring Austyn back but I think anything under $100,000 is a weak fine,” Rebeccah added.

For the fine, a joint submission was based on a number of things, according to the Crown: the nature of the incident; the gravity of the offence; and the fact a young person’s life was lost.

According to the defence, the operation had no blemish on its safety record and a sophisticated safety system prior to Austyn’s death.

One oversight, however, was transporting slabs in a wooden crating system that could shift. The company — of no more than 15 to 25 people at any given time — now uses steel.

The Crown also explained outside of court that sadly, tragic cases like this are not that unique.

“Very often, these very small businesses employ other family members and this is not the first time a family member has died working for the family’s company,” Buffy Rodgers said.

The only shining light in all of this, said the judge, is Austyn’s death may benefit people by reminding both parents and employers to never let their guard down.

“Safety needs to be your No. 1,” Rebeccah said.

“Carmont did have a safety program and they failed — a lot of companies don’t.”

Comments